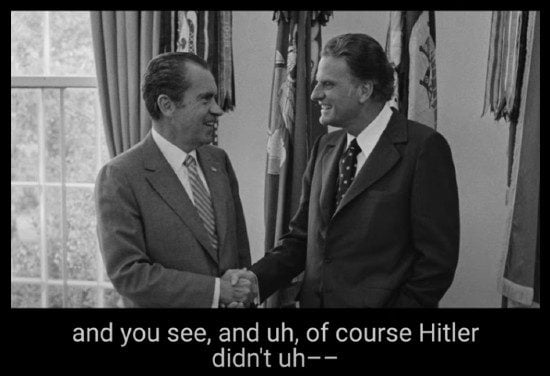

The first time I heard about this was from the denial, back in 1994. The Haldeman Diaries had just been published, providing new details about the Watergate scandal(s) that ended the presidency of Richard Nixon, for whom H.R. Haldeman had served as chief of staff.

Haldeman described a 1972 Oval Office conversation between Nixon and evangelist Billy Graham in which the president had referenced antisemitic conspiracy theories and Graham had agreed, lamenting an imagined Jewish “stranglehold” over the country. Graham emphatically denied ever saying such a thing or ever having any such conversation.

And that was that. Who were you gonna believe? A disgraced political hatchetman who went to prison for three counts of perjury? Or Billy Graham? The whole business was shrugged off as just one more dishonest attack by Nixon’s former attack dog.

The second time I heard about this was from Billy Graham’s apology, eight years later. Excerpts from Nixon’s White House audio recordings confirmed Haldeman’s account. Here’s how Debbie Lord summarized that revelation and Graham’s apology in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution:

At first, Graham denied comments Haldeman made in his book, The Haldeman Diaries that Graham and Nixon had disparaged Jews in a conversation following a prayer breakfast in Washington D.C. on Feb. 1, 1972. Haldeman said Graham had talked about a Jewish “stranglehold” on the country.

”Those are not my words,” Graham said in May 1994. ”I have never talked publicly or privately about the Jewish people, including conversations with President Nixon, except in the most positive terms.”

Graham was believed and the matter dropped until 2002 when tapes from Nixon’s White House were released by the National Archives. The 1972 conversation between Nixon and Graham was among those tapes, and Graham had to face the fact that he had been recorded saying the things of which Haldeman accused him.

The tapes proved damning.

”They’re the ones putting out the pornographic stuff,” Graham had said to Nixon. The Jewish ”stranglehold has got to be broken or the country’s going down the drain,” he continued.

Graham told Nixon that Jews did not know his true feelings about them.

”I go and I keep friends with Mr. Rosenthal (A.M. Rosenthal) at The New York Times and people of that sort, you know. And all — I mean, not all the Jews, but a lot of the Jews are great friends of mine, they swarm around me and are friendly to me because they know that I’m friendly with Israel. But they don’t know how I really feel about what they are doing to this country. And I have no power, no way to handle them, but I would stand up if under proper circumstances.”

Rosenthal was the Times‘ executive editor.

After the release of the tapes, Graham was horrified, according to Grant Wacker, a Duke Divinity School professor who wrote a book about Graham. He publicly apologized and asked for forgiveness from Jewish leaders in the country.

“He did not spin it. He did not try to justify it,” Wacker told NPR. “He said repeatedly he had done wrong, and he was sorry.”

”I don’t ever recall having those feelings about any group, especially the Jews, and I certainly do not have them now,” Graham said in 2002 when the tape was released. ”My remarks did not reflect my love for the Jewish people. I humbly ask the Jewish community to reflect on my actions on behalf of Jews over the years that contradict my words in the Oval Office that day.”

Graham’s biographer got spun. We now know that Wacker was wrong about Graham’s apology, which we now know was nothing but spin and attempts to justify his earlier, now-proven-false denial.

That apology was not confined to a single statement. It was a series of reactions and responses offered following the release of those excerpts all of which emphasized that Graham didn’t clearly recall participating in that White House conversation and that portrayed him as someone dazzled by the Oval Office setting and timidly falling back on just nodding along in agreement with Nixon’s hateful rant. In Graham’s telling, Nixon started going off about those supposedly nefarious Jews and he was caught flat-footed and tongue-tied. He apologized for not pushing back, for not criticizing the president’s comments and for not having the quick wit and courage to disagree forcefully when Nixon brought up this subject. “I was wrong for not disagreeing with the president, and I sincerely apologize to anyone I have offended,” he said.

Billy Graham was harshly criticized for those failures, but all of that criticism took the shape of Graham’s own description in his apology. See for example this piece by James Warren, the Chicago Tribune reporter who first unearthed the audio excerpts confirming Haldeman’s accusation and refuting Graham’s false 1994 denials: “Billy Graham’s Troubling, Nasty Nixon Moment.” Warren cites one criticism of Graham from historian Martin Marty, who said, “What Graham said that day is inexcusable. Did it ever occur to him that he should have countered the president?” And he quotes another Graham biographer, William Martin, who says something similar: “Should he have played the role of prophet rather than court chaplain and boldly spoken truth to power? Absolutely.”

David Neff’s article “Graham and the Jews: A Complex Connection” makes the same point, writing for Christianity Today:

The president took the lead in complaining about Jewish influence in politics and control of the media. But when he asked Graham if he believed that, the evangelist missed his Nathan-and-David opportunity to object to blatant ethnic prejudice. Instead, he agreed and added, “Not all the Jews, but a lot of the Jews are great friends of mine. They swarm around me and are friendly to me because they know that I’m friendly with Israel and so forth. But they don’t know how I really feel about what they are doing to this country. And I have no power, no way to handle them, but I would stand up if under proper circumstances.”

All of the articles above are from February of 2018 and all were published as sidebars to larger packages memorializing the iconic evangelist after his death at age 99. You can find dozens of articles just like those, all criticizing Graham according to the terms framed by his 2002 apology, holding him to account for “not disagreeing with the president.”

And while all of those writers were busy revisiting that 2002 story based on the excerpts from Nixon’s White House tapes, Mike Hertenstein was reaching out to archivists at the Nixon Library to gain access to the full, unedited audio — something that would only become available to the public after everyone who took part in “Conversation No. 662-4” (Nixon, Haldeman, Graham) had died.

The full conversation proves that Graham’s 2002 “apology” was a cynically dishonest work of pure spin. As Hertenstein wrote four years ago, the full version of the “Infamous Nixon Tape Makes a Bad Story Worse.”

As John Fea wrote after reading Hertenstein’s piece, the full recording makes it clear that: “Graham is directing and initiating the conversation. The authority and certainty in his voice is clear. He is no passive listener who is merely approving and affirming Nixon’s antisemitism. Nixon seems to be the one who is passive here.”

The framing of Graham’s apology for “not disagreeing with the president” — the basis for all those stories at the time of Graham’s death and of nearly all reporting about this conversation over the past 20 years — was fundamentally dishonest. Billy Graham visited the Oval Office to talk to the president of the United States about the evil Jewish conspiracy that he believed had a “stranglehold” on America. Graham was the one who brought this up and he was passionate about the subject. He went to the White House to plead with Nixon to use his second term to “do something” about the Jews and pledged to help however he could.

Graham’s repeated insistence that he didn’t recall this conversation seems even less credible due to a second tape released by the Nixon Library after his death. This is from a phone conversation a year later — a conversation in which Graham made a point of reminding the president of his previous warning about the “synagogue of Satan.”

We’ll return to discuss the vile substance of Graham’s remarks and of the toxic, antisemitic ideology he insisted he believed. Here I just want to emphasize how deliberately dishonest and misleading Graham’s denial and PR-focused pseudo-apology were. Billy Graham misrepresented the conversation he sought and started with the president and that misrepresentation became the accepted, official version for both his supporters and his critics over the next 20 years. His lie was repeated in numerous biographies and in countless obituaries, often held up as evidence of his humility and integrity.

Billy Graham went to the White House to lobby the president to support Hitler’s analysis of “the Jewish problem” — literally — and to “do something about it” as the centerpiece of his second-term agenda. Then he falsely denied having done so. And then he lied about what happened.