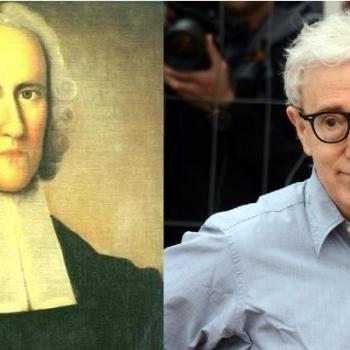

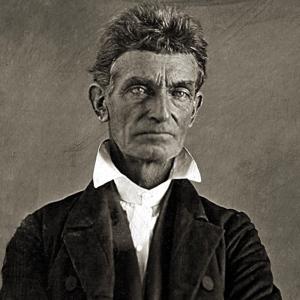

I appreciate this sneaky Christianity Today piece by Louis A. DeCaro Jr.: “Why White Evangelicals Should Claim John Brown.” (Sneaky in a good way.)

DeCaro is a scholar who has written several books about Brown, as well as a biography of Shields Green, a Black man who accompanied Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry. He knows John Brown well and, therefore, admires him. “I dream that John Brown’s soul might march again,” DeCaro writes.

And if you don’t understand why, he suggests that’s because — at best — you’ve been sold a bunch of lies about the man, what he fought for, and the meaning of his legacy:

Among white people, Brown was widely dismissed by the early 20th century. As American society backpedaled from the idea of Black people becoming full citizens, Brown’s reputation couldn’t help but decline. Whites in the North celebrated reunion with whites in the South and tacitly agreed to talk about the soldiers’ honor and bravery and set aside the actual issues that had separated patriots and traitors.

Slavery itself was sentimentalized in this era, with lots of popular rhetoric and images of “mammies” and “piccaninnies.” Those who benefited from the system of white supremacy were depicted sympathetically, while those who defended it were imagined to be noble.

Meanwhile Brown, who hated slavery more than he loved his own life, was portrayed as insane. …

The first draft of history … was mostly written by the proslavery press. The initial interpretation of Brown’s actions was crafted by people who believed that “all men are created equal” was a lie.

Before that, though, DeCaro reminds his white evangelical audience of this essential truth about Brown: He was one of us. Brown, he insists, was a man of “deep evangelical faith”:

Brown testified clearly to his own conversion, and he prayed that those around him would know “the grace of God through Jesus Christ.” He continually held up the Bible as the authoritative Word of God, the supreme written norm by which God binds the conscience. He urged people, “Be determined to know by experience as soon as may be, whether Bible instruction is of Divine origin or not,” convinced that if they tested the Scripture, they would discover the truth.

He backs this up with numerous examples and citations of Brown’s Bible-soaked words and letters, reminding us also of the great esteem he earned among devout Christians outside of America. DeCaro quotes the revered British evangelical preacher, Charles Haddon Spurgeon, who wrote that John Brown was “immortal in the memories of the good in England” and that “In my heart he lives.”

That Spurgeon reference is DeCaro’s version of Cleavon Little in Blazing Saddles saying “You’d do it for Randolph Scott.” He knows he’s writing for an audience of white evangelical pastors who routinely rely on collections of Spurgeon quotes to spice up their sermons.

CT’s editors shrewdly recognized that too, which is why they plucked that detail from deep in DeCaro’s piece and used it as a subhed: “We’ve forgotten what Charles Spurgeon knew …” That’s smart. The Spurgeon angle is more likely to entice their readership to engage with this article than a reference to “Bleeding Kansas” would’ve been.

The headline those editors gave to DeCaro’s piece was also cleverly designed to appeal to this audience, but here the appeal is more ambiguous. What does it mean to say that “White Evangelicals Should Claim John Brown”?

DeCaro’s actual argument is that 21st-century white evangelicals ought to listen to John Brown. He lays out the case that Brown belongs squarely in the category of “evangelical Christian” (provided one sticks to theological parameters rather than the cultural parameters Brown emphatically opposed). Brown’s words — and deeds — were expressed in the native language of evangelical Christianity and DeCaro very much wants contemporary white evangelicals to contend with the still-living witness of their brother John.

But DeCaro is not at all doing the other thing the headline seems to be attempting, arguing that contemporary white evangelicals should “Claim [Credit For] John Brown.”

This recalls my ambivalence about the use and misuse of Donald Dayton’s terrific little history Discovering an Evangelical Heritage. Dayton’s book is a collection of exceptional stories about exceptional people who excepted themselves from the prevailing spirit of their time to fight against grave injustices that were seen by the overwhelming majority of their contemporary white Christians as utterly unexceptional. The stories he collects and retells are inspiring and challenging and unsettling precisely because they are extraordinary.

Dayton’s book, in other words, is tremendously helpful if we view it as a reminder of the witness of all of these disregarded prophets, learning from that by striving to better heed the voices and witnesses of the prophets we have among us today. But those same stories become corrosive and toxic if we read them defensively, trying to “claim” their extraordinary, exceptional witness as typical of “our” heritage and “our” legacy.

David Swartz wrote a terrific piece about that last summer: “Innocent Readings of Evangelical History.” (I responded to that here.) Here is the heart of Swartz’s sermon:

The inspirational stories that moderate evangelical institutions tell about themselves aren’t helping. Many marshal a usable history to convince themselves that their tradition is not rotten at the core. Former George W. Bush speechwriter Michael Gerson, for example, appeals to historical examples of 19th-century abolitionists and suffragettes. Wheaton College cites Jonathan Blanchard, its first president who made campus a safe stop on the Underground Railroad during the Civil War. Wesleyans, mining Donald Dayton’s Discovering an Evangelical Heritage …, point out that Methodists helped launch the women’s suffrage movement, that missionary E. Stanley Jones integrated evangelistic crusades — soon followed by Billy Graham.

To square this impressive evangelical past with the sordid present, they use the narrative device of historical declension. Evangelicalism, moderates maintain, has declined from its former enlightened stances on issues of social justice. Billy Graham’s legacy has been coopted by his son Franklin. James Dobson, the apolitical psychologist who began tasting the delights of political power, became a culture warrior. Evangelicals who never would have supported Donald Trump in the 1970s voted for him en masse in 2016 and 2020. If contemporary evangelicals would only know their enlightened history — and stay true to it — they would be more willing to say that Black lives matter.

The problem is that these narrations cherry-pick unrepresentative voices from the past. Abolitionists never really represented the mainstream of [white] evangelicalism. There were always more slaveholders than Grimké sisters. Leaders who want to minimize (or distract from) evangelical support for Trump narrate the movement as more cosmopolitan than it has actually been. They peddle what Cuban-American theologian Justo González calls “innocent readings of history.” They minimize the bad, emphasize the good, and ignore how moderation often perpetuates injustice. They portray their own history as more innocent than it actually was.

Despite that headline about “claiming” John Brown, DeCaro clearly is not interested in this kind of “innocent reading of history.” This is John Brown we’re talking about here, after all — someone whose whole life bears witness to the fact that an innocent history is not an option for any American, Christian or otherwise. He is fully aware that John Brown is extraordinarily extraordinary — a uniquely unrepresentative voice from the past who defies any attempt by us to “claim” him as our vicariously righteous, hashtag-Not-All representative. And he is valiantly appealing to Brown’s extraordinary voice against strong currents of whitelash and a moral panic over “CRT” and “wokeness.”

I think the CT editors use of that “claiming” language was probably less an actual attempt to do that as it was a way of using that unseemly appeal to entice its readers to engage with DeCaro’s richer, more subversively challenging argument. Or, at least, I hope so.

Either way, though, the hint of such an appeal using John Brown is, itself, an intriguing development.

The attempt to conscript John Brown in support of an “innocent reading of history” is a backhanded concession that John Brown was right. Yes, as Jesus said in Matthew 23, the elaborate building of tombs for the prophets is usually an exercise in hypocrisy. But it thus also serves as “the tribute vice pays to virtue” — identifying, locating, and reaffirming that virtue in spite of itself.

That, in itself, never stops anyone from flogging the prophets now among us in our churches and pursuing them from town to town. Cognitive dissonance, by itself, can’t be relied on to stop anyone from saying, “We are the righteous heirs of the righteous abolitionist Blanchard and therefore our righteousness cannot be questioned as we fire a Black professor with tenure for prophesying against bigotry.”

But still, the admission has been admitted: John Brown was right.

Stick a pin in that. Poke at that pin, forcing it under the skin and making sure that it can’t be ignored or forgotten. Make them say it. Make them own it. Make them claim it.