Alaric Dearment writes about the “Log Cabin Republicans” now enthusiastically supporting the denial of basic rights for people like themselves:

Maybe that’s because they think this is all fun and games. Maybe they think the GOP’s homophobia and transphobia is just politics and isn’t real. Maybe they think that if the generation-long conservative Supreme Court majority secured by Trump overturned Obergefell or even Lawrence, their connections, wealth and political affiliation would protect them. Maybe they think it’s okay to side with fascists because they’re “good” right-wing gays, not “bad” liberal ones and will thus be safe.

It’s tempting here for me to point out parallels between these Pro-Anti-Gay gay men and, say, the “complementarian” pastors wives of Ladies Against Women. In both of those cases, though, it might seem that I’m sticking my nose into someone else’s business. After all, I am neither LGBT nor a woman in a patriarchal denomination, so I should probably, as they say, “stay in my lane.”

But the corrupt and doomed bargain Dearment describes involves a failure of solidarity — a betrayal of others resulting from the betrayal of solidarity. And the duty of solidarity doesn’t just apply within discrete groups. It’s universal. The obligation of solidarity, I suspect, weighs more heavily on those of us fortunate enough not to be in the crosshairs of the cultural fascists. I think the duty to stand up to bullies, to oppose them and stop them, is greater for those of us who are not ourselves the targets of those bullies.

It’s not my place, in other words, to say whether or not people like Dave Rubin and Caitlyn Jenner have a particular duty to stand up in defense of other LGBT people as they’re being targeted, smeared, slandered, and oppressed. My part in this, rather, is to point out that people like me have an even greater obligation to do so. That’s how the duty of solidarity applies to me, and to others like me, and we can’t dodge that duty by distracting ourselves with abstract discussions of how it might apply to others.

This is why I found Jay Rosenblatt’s Academy Award-nominated documentary short When We Were Bullies intriguing, but ultimately frustrating.

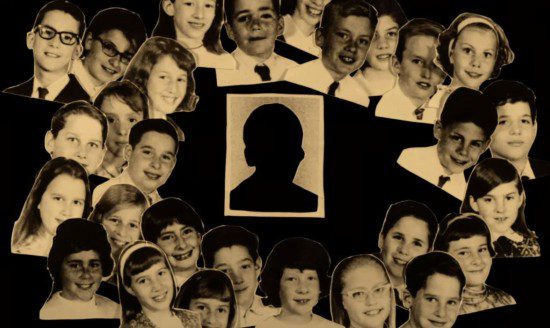

More than 50 years ago, Rosenblatt and most of his fifth-grade classmates mocked and tormented that one weird kid who didn’t quite fit in. He tracks down many of those classmates and finds that many of them, decades later, are still haunted by the cruelty they displayed as children. Their regret and remorse is palpable, but it never seems to solidify into resolve. And so the film seems like a quest for absolution without resolution.

The former fifth-graders remain unsettled by the realization that they were personally capable of standing by — or even of participating — when bullies preyed on the weak. And from there they come to the true realization that it seems everyone is capable of this. But the next realization and the next step doesn’t come. They seem to view this universal human capability for cruelty and cowardice as exculpatory — as something that not only excuses their long-ago failure, but that also serves as a blanket excuse going forward.

(I’d like to see one of my Girardian friends wrestle with Rosenblatt’s little movie. When We Were Bullies surely seems related to Girard’s insights about scapegoats, but I’m also pretty sure that the idea isn’t supposed to be “Hey, we humans love our scapegoats, whatcha gonna do? Shrug emoji.“)

American politics in 2021 seems shaped by the same bullying instincts Rosenblatt and his classmates recall from that fifth-grade playground. The former guy was a bully and all of his imitators — Greg Abbott in Texas, Ron DeSantis in Florida, and a thousand other Mini Mes in Congress and statehouses across the country — are doubling down on the electoral arithmetic of schoolyard bullies.

For a cynic or a nihilist, that arithmetic seems promising. The victims of bullying, after all, are always outnumbered. And the majority of the schoolyard will just stand by as bystanders, unwilling to challenge the bullies’ claim to their divine right to rule lest they turn their attention to us. We hope they’ll leave us alone, and so we leave them alone — which is to say we leave them in charge.

It’s no coincidence that the politics of bullies is now being directed at exactly the same people it targeted back in grade school and middle school and high school — the queer kids. They’re an easy target — different, small in number (trans folks are something like 0.5% of the population), and unprotected by the herd.

The exact same people who bullied those kids back in grade school are now bullying those kids from the highest offices and seats of power, and the exact same people who stood by and let it happen back in school are doing the very same thing again. And so the bullies are still in charge.

When We Were Bullies fails, I think, because it is a story without heroes, and a story without heroes isn’t really a story at all. No one in the story has resolve, and so the story lacks resolution. The past-tense of Rosenblatt’s title turns out to be misleading. We Were Bullies, and We Haven’t Changed.

So where are the heroes? Where are the people that good stories show us standing up to the bullies, standing for and standing with their victims? We wait, looking around for those people to show up because maybe, if they do, they’ll save us too — save us from the nagging shame, remorse, and regret that’s sure to be our lot as bystanders.