Chris Gehrz and Ezra Klein revisit a novel that has become more salient in the age of Trump: Philip Roth’s The Plot Against America.

“Philip Roth’s 2004 warning about demagogues is more relevant than ever,” Klein writes. It is, he says:

… a work of alternative historical fiction imagining a world where Charles Lindbergh drove Franklin D. Roosevelt from office. As we mourn Roth’s passing, it is worth remembering his warning.

Roth’s Lindbergh sweeps to the presidency on, literally, an “America First!” ticket. He takes over a fractured Republican Party and campaigns against the advice of consultants and politicians, flying his own plane around the country, offering plainspoken denunciations of interventionism and identity politics.

“We cannot blame them for looking out for what they believe to be their own interests, but we must also look out for ours,” says Roth’s Lindbergh of the Jews. “We cannot allow the natural passions and prejudices of other peoples to lead our country to destruction.”

This, throughout The Plot Against America, is Lindbergh’s message: that America is being taken advantage of, that it has lost sight of its own needs amid the clamoring of its interest groups, that its diversity has become a weakness, that the world will only respect us if we elect a leader whose steel they fear.

In the novel, Lindbergh is elected, ushering an era 0f 1930s-style fascism right here in America, complete with pogroms, ethnic cleansing, and the full Herrenvolk nightmare. It’s extreme, but not far-fetched. In many ways, Klein argues, the book seems less far-fetched than the reality of the current moment:

The world Roth paints is more believable than our own. That is why its warning was so prescient. Even before Trump, Roth knew what much of America’s political class had forgotten: that the boundaries of the possible were wider than either the Democratic or Republican parties believed, that isolationism and xenophobia are powerful tools in the hands of a charismatic political outsider, that there is nothing in the American heart that inoculates us against the allure of demagogues.

… The Plot Against America resonates because it is about us, because it is convincing in its argument that it can happen here, that there will always be those among us who want it to happen here, and if we are not vigilant, someday, it will.

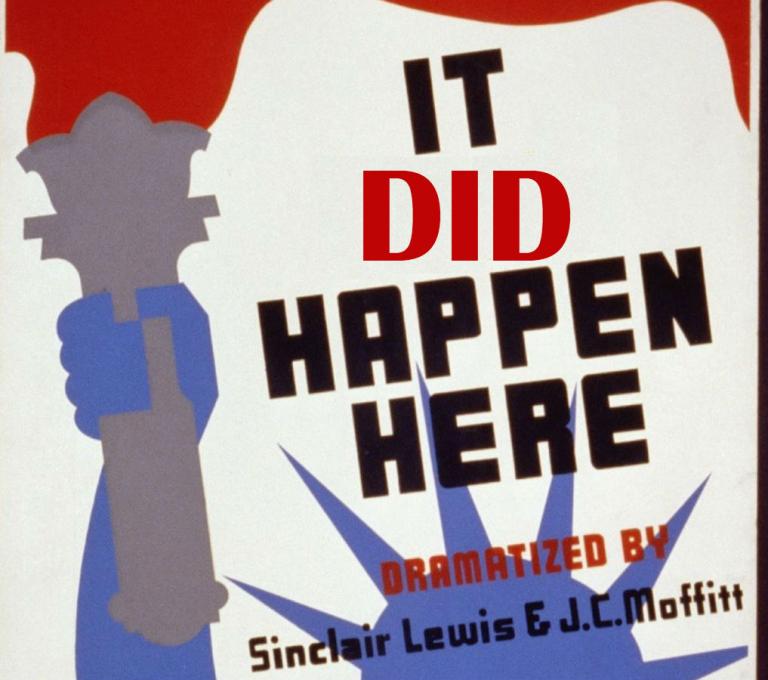

That phrase “it can happen here” comes from the title of a 1935 novel by Sinclair Lewis, It Can’t Happen Here. Lewis’ darkly comic novel follows the ascendency of a red-blooded American fascist demagogue named Buzz Windrip, who rises to become our very own Mussolini or Hitler. The title was ironic — “It Can’t Happen Here” was the ineffectual, complacent denial of most American citizens that prevented them from challenging what they were seeing.

Windrip was probably modeled more after Huey Long than Lindbergh. The aviator was still a national hero in 1935, and didn’t fully, publicly disgrace himself with his anti-Semitic views and isolationist nativism until a few years later. I’m interested to see what Chris Gehrz will have to say about that ugly turn in Lindbergh’s life in his upcoming “spiritual biography” of the man who was, for many years, the most famous and most admired American. That assignment is also part of why Gehrz turned to Roth’s novel.

Of course, a work of speculative fiction isn’t ideally suited as biographical research. Gehrz writes:

Roth quotes the most damning of Lindbergh’s written and oral statements from a period that reversed his standing in American opinion. But ultimately, he seems unsure what to make of his novel’s central villain. … It doesn’t shed all that much light on the man whom Philip’s mother calls “a goyisch idiot flying a stupid plane.

But, like Klein, Gehrz says the book does shed light on us — on America and our potential susceptibility to the kind of demagogic fascism Roth’s alternate history portrays:

It’s hard not to feel queasy reading The Plot Against America in a time when fascism has reentered our domestic political vocabulary: when an American president hesitates to condemn neo-Nazis and the national news barely notices when someone spray-paints swastikas on hundreds of graves.

He concludes by quoting the same passage from Klein’s essay that I’ve quoted above.

Much of Gehrz’s post is not so much about Roth’s novel in particular as about the genre of “alternate histories” in general — and especially about such alternate histories that, following Sinclair Lewis, explore the potential or possibility that it could happen here.

The deeply frustrating thing about this genre is something neither Gehrz nor Klein mentions: It already did happen here.

Maybe not the very particular form of “it” addressed by Sinclair Lewis — European-style strongman fascism a la Mussolini or Hitler, but something far more pervasive and enduring. These “alternative histories” are speculative, but we have no need to speculate. This is already our history — for centuries.

We forget this. We forget it reflexively, aggressively, perpetually, as a defense mechanism. And thus when someone like Ezra Klein writes “it can happen here … and if we are not vigilant, someday, it will” we read this as ominous rather than, as it should be, obvious.

What does “it” mean — in practice, in detail? “It” entails the subjugation and marginalization of religious and ethnic minorities, ethnic cleansing, and, ultimately, genocide. That’s all been done. And unlike the relatively brief span of fascist madness that burned through 20th-century Europe, this happened here for generations. It was enshrined in our Declaration, our Constitution, our laws, courts, mores, manners, and doctrines. It shaped our towns and cities, our churches and schools. It shaped everything.

And until we reckon with that — until we unshape everything shaped by it, it will happen here again. Because for many here, it never stopped happening.

I love that old Sinclair Lewis novel. It’s warning was wise, insightful and utterly necessary. But it was also circumscribed and limited by that automatic American forgetting. It Can’t Happen Here was a timely warning in 1935 and it sadly remains a timely warning in 2018.

But there’s a sense that its warning, like the warning Gehrz and Klein find in Roth’s novel, could be restated this way: If we are not vigilant, then even white Christian Americans might some day find themselves subject to the same lawless oppression that black people and Native Americans have faced for the past 400 years.

It did happen here. And for far too many of us, it’s happening right now.