(Originally posted October 9, 2009. This got lost in the migration from TypePad to WordPress, recovered and reposted for the archives here thanks to Loki1001 and the Library of Congress.)

Tribulation Force, pp. 104-105

We’ve read the set-up for this.

Buck Williams has headed off to New York without telling Chloe because he didn’t want her to talk him out of his meeting with Nicolae. Meanwhile he’s given spiky Alice the key to his apartment so that she can drop off the things arriving from his old office before she heads to the airport herself to pick up her fiancé. So the stage is set and here we come to the scene.

It unfolds, of course, on the telephone. Rayford dials his daughter, who is screening her calls with the answering machine:

Chloe grabbed the phone. She sounded awful. “Hi, Dad,” she mumbled.

“You under the weather?”

“No. Just upset. Dad, did you know that Buck Williams is living with someone?”

“What!?”

“It’s true. And they’re engaged! I saw her. She was carrying boxes into his condo. A skinny little spiky-haired girl in a short skirt.”

You can’t miss with the classics. Unless you’re Jerry Jenkins. Because here, in Tribulation Force, even this standard, tried-and-true plot device is mishandled.

It should be automatic. The instructions from the Acme Romantic Comedy factory are clearly written and all Jenkins needed to do was remove the prefabricated plot device from its packaging and insert it into his novel.

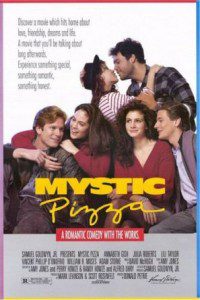

The Not What It Looks Like confusion of innocent behavior as infidelity may not be the most sophisticated plot device in the catalog, but if installed properly it works. Sure, it’s a gimmick, but it’s a reliable gimmick. It turned Julia Roberts into a movie star in Mystic Pizza. It generates conflict through innocent confusion, allowing audiences to sympathize with both parties without finding fault in either. And the conflict is easily resolved, lasting only as long as it is needed to introduce just enough tension or to bring to the surface the characters’ unspoken or unrecognized affection.

Shakespeare employed several variations of this device. Don John, the poor man’s Iago, sets the plot of Much Ado About Nothing* in motion by deliberately creating just such a case of Not What It Looks Like (or, actually, Not Who It Looks Like, since Borachio and Margaret really are doing what it looks like they’re doing). That play illustrates both the sturdy reliability of this plot gimmick and its limitations. The manufactured conflict between Claudio and Hero works, but it’s never as interesting as the character-driven conflict between Benedick and Beatrice.

Here in Tribulation Force Jenkins — being Jenkins — makes a hash of this classic can’t-miss plot twist. First he botches the set-up, then he puts the thing in backwards, and then he compounds the problem by dragging the whole thing out far longer than it could ever reasonably be sustained, and then longer still, and then even longer still, and then a bit more until finally the reader winds up wishing Iago himself would show up and hand someone a pillow.

Before we get to those problems in more detail, here’s a bit more of Jenkins’ description of how this played out. After seeing Alice carrying boxes into Buck’s condo, Chloe says:

“I was so mad I just drove around a while, then sat in a parking lot and cried. Then around noon I went to see him at the Global Weekly office, and there she was, getting out of her car. I said, ‘Do you work here?’ and she said, ‘Yes, may I help you?’ and I said, ‘I think I saw you earlier today,’ and she said, ‘You might have. I was with my fiancé. Is there someone here you need to see?’ I just turned and left, Dad.”

“You didn’t talk to Buck then?”

“Are you kidding? I may never talk to him again.”

The first problem with all of this is that Chloe isn’t really wrong. We’ve seen Buck and “Anything for you” Alice in action and theirs does not seem to be a wholly innocent professional relationship. Alice seems, in fact, like she really is a rival for Buck’s affection, one who appears so far to be winning. All that giggling and wide-eyed leaning forward and jumping at the chance to drive all over lugging boxes for Buck shows us that Alice is clearly smitten. And Buck finds nothing quite so attractive as a woman with the good judgment to be smitten with him.

The guiltily belated reference to the existence of Alice’s fiancé didn’t do anything to dispel the sense that those two need to get a room. The mention of this fiancé didn’t communicate to readers that Alice is engaged and therefore not interested in Buck, but rather that this poor schmo of a fiancé just doesn’t realize he is losing his girl to a superior man.

I think Jenkins wanted the fiancé to signal that Alice was spoken for and therefore not a rival of Chloe’s, but he just couldn’t resist his compulsion to demonstrate that Buck is the Alpha Male and that Alice’s fiancé can have her affection only if Buck allows it. Buck/Rayford has to be given first dibs on any woman in the story, otherwise the authors fear that we might suspect that woman impossibly might actually prefer some other man over our heroes/authors.

That’s all part of the insufferable perfection the authors intend for us to see in their heroes. Such perfect men, of course, can never be wrong — not even innocently mistaken. And that’s why Jenkins decided to stick this plot device in backwards. Instead of having his protagonist confused by an innocent mistake, he forces this confusion onto poor Chloe — the object of the protagonist’s affection.

That’s not how the gimmick works and it creates several problems here.

Chloe isn’t a point-of-view character in this book, so we’re only able to see her confusion and her sense of betrayal second-hand via Rayford. This makes her seem less sympathetic — more petulant and vindictive than she might have seemed if we had been given her reaction first-hand. We aren’t invited to consider the conflict as it appears to Chloe, but rather as it appears to Buck. This makes our hero Hero — virtuous and wrongfully accused (reinforcing the persecution complex at the heart of these books). Chloe comes across less like the innocently deceived Claudio than she does like Don John — a cruel, spiteful accuser. At best, in the authors’ view, she is meant to seem foolish, since only a fool could ever suspect Buck Williams of wrongdoing or, for that matter, of having any flaw whatsoever.

It doesn’t help Chloe any that we readers know all along that she is mistaken. We know better, so we never participate with her in her confusion. We may try to understand it, but we don’t share it. It’s her mistake, not ours.**

The implicit message thus is not “We humans sometimes jump to the wrong conclusions based on incomplete information and a fear of losing what we cannot live without,” but rather, “Chloe is a girl and girls are silly.”

And that’s really the fundamental problem here. The rest of this might be surmountable — even the authors’ suffocating self-love for Buck as Mr. Perfect — were it not for the way this subplot reinforces these books’ relentless misogyny.

Chloe isn’t portrayed throughout this episode as a victim of circumstance making an innocent mistake. She’s just a woman, and in LaHaye and Jenkins’ universe, women are inherently foolish, rash and unreliable. They are drama queens in need of firm guidance from men, who are far more reasonable and wise and fully human.***

This Not What It Looks Like subplot, dragged on ad nauseum over the next several chapters, offers the authors’ neatly circular defense of this misogyny. Chloe is portrayed as foolish because she is a woman. And it’s not unfair to portray women this way, because just look at what Chloe is doing.

– – – – – – – – – – – –

* In Elizabethan slang, “something” and “nothing” were sometimes used to refer, respectively, to male and female genitalia. The title of Much Ado About Nothing is thus not simply a reference to the illusory conflict at the heart of the plot, but also a nifty dirty pun.

** This is something Mystic Pizza actually does better than Much Ado, in which the audience knows all along that Claudio is deceived and never shares in that same deception. This can make Claudio unsympathetic — a potential disaster, since Hero’s restoration and happiness involves her receiving Claudio as her reward, and if the audience doesn’t like him, then it seems like she’s getting doubly cheated. This is why I think the actor playing Claudio has to have a beautiful singing voice. If he sings like an angel in Act V, the audience will usually forgive him for acting like a prick in Act IV.

*** This is just a theory, but this pervasive disdain for women — the sense that their opinions do not really matter — may be one factor (if not the only one) in these books’ hilariously omnipresent homoerotic subtext.

Buck and Steele are presented as paragons of manliness who, by definition, deserve the adoration of every woman. And yet, also by definition, no woman can be presented as genuinely deserving them. This creates a problem. Illustrating their virile manliness requires that readers be shown others as perceiving them and responding to them as irresistibly sexually desirable. Yet for that desire to be credible and respectable it cannot come only from mere women. Women’s opinions don’t really count. Thus it falls to the other men in the story to express that sexual desire in a way that is, for the authors, credible and convincing.

Oscar Wilde, I think, made playfully deliberate use of something like this in The Importance of Being Earnest, employing his male protagonists’ chauvinism as a kind of mask for their clear preference for flirting with one another, a la Beatrice and Benedick.

A darker example might be Frank T.J. Mackey, Tom Cruise’s predatory sex guru in Paul Thomas Anderson’s Magnolia. Mackey seems like the inverse of what we have here in Tribulation Force. His repressed homosexuality is channeled into a vicious misogyny. The authors here fully embrace Mackey’s credo: “Respect the cock! Tame the [nothing]!” but for them the dynamic works the other way — with their vicious misogyny getting channeled into an inadvertent homoeroticism.

But like I said, it’s just a theory.