(Originally posted July 17, 2009. This got lost in the migration from TypePad to WordPress, recovered and reposted for the archives here thanks to Andrew G. and the Library of Congress.)

Tribulation Force, pp. 60-63

So the second thing that needs to be said about this sermon by the Rev. Bruce Barnes is that it’s not very good.

Well, to say that Bruce’s sermon isn’t very good would be like saying the Great Wall of China isn’t very short. But it wouldn’t have mattered much if this had been a good sermon, or even a great sermon, because the first thing that needs to be said about this sermon here is that it’s simply the wrong sermon — the wrong sermon at the wrong time, for the wrong audience, delivered in the wrong way.

That’s not how Rayford Steele thinks of it. He sits in the pew anticipating another thrilling dose of his favorite sentiment: earnestness.

Few people who sat under the earnest and emotional teaching of Bruce Barnes could come away doubting that the vanishings had been the work of God. The church had been snatched away, and they had all been left behind. Bruce’s message was that Jesus was coming again in what the Bible called “the glorious appearing” seven years after the beginning of the Tribulation. By then, he said, three-fourths of the world’s remaining population would be wiped out, and probably a larger percentage of believers in Christ. Bruce’s exhortation was not a call to the timid. It was a challenge to the convinced, to those who had been persuaded …

Jesus is coming again again. It’s a bit confusing to read this summary of “Bruce’s message” before Bruce gets up and delivers that message, but it suggests part of the problem with what is to follow here. The paragraph quoted above comes immediately after the one that describes the congregation of New Hope Village Church as “grieving,” “terror-stricken” and “looking for hope.” So Bruce gets up to give a sermon that is, expressly, not for the timid, but for those already wholly convinced and persuaded and fearless.

To see how this plays out, let’s skip ahead four pages to the introduction to Bruce’s sermon itself:

My sermon title today is “The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse,” and I want to concentrate on the first, the rider of the white horse. If you’ve always thought the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse was a Notre Dame football backfield, God has a message for you today.

This will again strike evangelical readers as reassuringly familiar. They’re accustomed to sermons that start off with nervously jokey pop-culture references from 1924.

But those readers aren’t just the intended audience for this book, they’re also the intended audience for this sermon within the book. Bruce’s sermon is designed to be read by pre-Rapture American evangelical Christians — by people sitting comfortably at home, convinced and persuaded of their own salvation, their un-disintegrated children contentedly watching Bibleman videos in the next room. For that audience, Bruce’s sermon might make a warped kind of sense. But for the audience there, in the book, in the pews of New Hope Village Church, this sermon would be intolerably, cruelly irrelevant.

There’s only one sermon, one topic, that this traumatized, grief- and terror-stricken congregation needs to hear on this occasion: “What Happened to Our Children?”

This is the only thing that would matter. The only thing. That would be true even to those in attendance who had no children of their own — even to those who didn’t even know any children. Missing children require an explanation. They require a metaphysical accounting. That need, that demand, transcends any specific connection to any specific child. When children are taken, there are things we all demand and require to know.

I moved to Everybody’s Hometown shortly after the accident and I had lunch that week with a friend who serves as a pastor there. Five teens from the local high school had been riding together in a car that was going too fast to negotiate a notorious curve. Some of the funerals were at my friend’s church. He was exhausted, beaten down. During the course of that meal, he cycled through all of Kubler-Ross’ stages of grief several times over.

Five children in a town of about 10,000 turned out to be an unbearably high percentage. The families were distraught. The high school was devastated. No one in town seemed untouched or unaffected or unscathed. People needed answers and many of them were turning to my friend. He is a wise man with a rock-solid faith, but when I met him for lunch that day he seemed to want to run away or hide or beat the rock like Moses and scream at the silent heavens.

In the preceding 60 pages of Bruce Barnes’ moaning and whining about his “heavy burden,” he hasn’t once mentioned this burden. He hasn’t once confronted or been confronted with the unanswerable questions about the missing children — where? how? why? — or with the hollow inadequacy of the pat answers he has to offer in response. God took them. They’re with God. It’s all for the best, so there’s no need to conduct or consider or even mention the possibility of funerals for the disappeared. Let’s just quickly move on already to the business at hand of digging a really big hole for Pastor to hide in.

By not confronting any of that in his sermon, Bruce creates a situation in which the best possible outcome would be people walking out en masse. More likely, there’d be a riot. (“His God did this? Let’s get him! Burn the church!”)

Then again this is the third Sunday since the Event. Perhaps Bruce dealt with all this last week. But that won’t do either. This is not a one-lecture problem in need of a one-lecture fix. Even if he did preach about all those missing children last week, what of it? They’re still missing.Their empty rooms and their tangible, ever-present absences are still the black holes at the center of every family — the all-consuming devourer of light around which everything else slowly orbits.

Bruce is eager to skip ahead to the next item in his End Times check list, to make some progress through the litany of judgments listed in the book of Revelation. That litany, we’ve noted before, is a variation on an older theme. John of Patmos assesses the Roman oppressor and suggests this Caesar is nothing more than the latest Pharaoh, so he invokes against him all the plagues of Egypt.

In LaHaye and Jenkins’ reimagining of Revelation, they embellish that book’s listing of the plagues, adding the one that’s missing and reordering the list so that it comes first instead of last. And then they up the ante. It’s not enough of a blow in their view for death to come to the first-born of every family, they have to take away every child.

They never grasp how this alters and undermines what Revelation presents as an escalating series of calamities. All the earthquakes and locusts and hail-and-fire-mixed-with-blood come across as wan and anticlimactic after every parent on earth has already been subjected to every parent’s worst nightmare.

Go ahead and ask any parent, even the worst parent you’ve ever met, ask them which they would choose to have happen, if they had to choose: The inexplicable and instantaneous disintegration of their child? Or merely something like this:

… a great earthquake. The sun turned black like sackcloth made of goat hair, the whole moon turned blood red, and the stars in the sky fell to earth, as late figs drop from a fig tree when shaken by a strong wind. The sky receded like a scroll, rolling up, and every mountain and island was removed from its place.

That’s the sixth seal of judgment from the sixth chapter of Revelation. It sounds bad, but not nearly as bad as the Event. Who really cares if “every mountain and island” is removed from its place after every infant and child has been removed from theirs?

The pages we skipped past a moment ago are filled with Bruce Barnes’ long and rambling throat-clearing introduction to his sermon in which Bruce says, about six different ways, that he has something desperately urgent to tell everyone. You get the sense that if a large object were falling toward your skull, Bruce wouldn’t just yell, “Duck!” but would, instead, say something like, “I want you to listen very carefully to what I’m about to say and not to dismiss it as the overwrought concerns of a religious zealot, but rather to appreciate my earnest sincerity and passion and to glean from that that attention ought to be paid to the desperately urgent warning I intend to deliver to you shortly …”

Here’s how Bruce begins:

I realize a word of explanation is in order. Usually we sing more, but we don’t have time for that today. Usually my tie is straighter, my shirt fully tucked in, my suit coat buttoned. That seems a little less crucial this morning.

What Bruce ignores, probably because he’s been re-reading Revelation instead of talking to any of his neighbors, is that the congregation is in even worse shape than he is. The Steeles may have “dressed for God” this Sunday morning, but the rest of these people haven’t done laundry or shaved or slept since their kids disappeared.

Reaching for some kind of analogy for the unimaginable aftermath of the Event, I keep comparing it to something more familiar, like a mining disaster. We’ve discussed how communities faced with such tragedies do tend to congregate at churches. But they don’t show up freshly scrubbed and dressed in their Sunday finest. They show up in whatever they happened to have on when they heard the news — in jeans or sweats or even bathrobes hastily grabbed on the way out the door. This Sunday gathering isn’t exactly like that, but it’s far closer to that than either Bruce or the authors realize.

And that brings us to the strangest, cruelest aspect of this Sunday service and the sermon Bruce delivers: It’s like a service after a mining disaster in which no one even mentions the miners. No one prays for them or for their families. No one discusses funeral arrangements or any other way for the community to acknowledge and begin to cope with the pain and loss. No one weeps with those who weep and no one mourns with those who mourn.

Once again we find ourselves up against a wall in reading these books. We can’t move on without accepting the authors’ framework, which requires them, and us, to work our way rat-a-tat through the discrete and unrelated events on the End Times check list. We cannot continue reading if we’re going to dwell on the meaning or repercussions of events that have already been checked off. Nor will we be able to continue reading if we expect the characters in these pages to respond or react or change as a result of those over-and-done-with occurrences.

Once again we find ourselves up against a wall in reading these books. We can’t move on without accepting the authors’ framework, which requires them, and us, to work our way rat-a-tat through the discrete and unrelated events on the End Times check list. We cannot continue reading if we’re going to dwell on the meaning or repercussions of events that have already been checked off. Nor will we be able to continue reading if we expect the characters in these pages to respond or react or change as a result of those over-and-done-with occurrences.

So, yeah, the kids are all gone. That’s over with. It was in the previous book; this one’s about the next thing. If Rayford, Buck, Bruce and everyone else in the world of this story can casually move on without giving those missing children a second thought then we, as readers, must be expected to do the same.

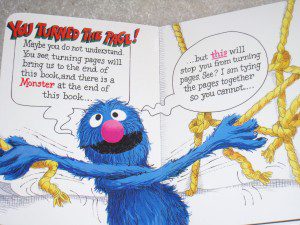

Other stories in other books persuade readers to go along through the willing suspension of disbelief. Tribulation Force insists on the willing suspension of the reader’s humanity. It requires the reader not just to accept but to participate in the monstrous absence of empathy displayed by the characters and authors alike. The word empathy has recently become something of a partisan football, so it’s worth reminding ourselves here of what the opposite of empathy is: sociopathy.

There’s a monster at the end of this book. And if the authors succeed at what they’ve set out to do, that monster is you.

That’s part of why one should only read these books slowly, in small, weekly doses, while pausing to scream at or mock every page.