(Originally posted in August, 2007. This got lost in the migration from TypePad to WordPress, recovered and reposted for the archives here thanks to Chris D., who saved a copy.)

Left Behind, pp. 256-258

The rest of this chapter, as far as Buck Williams goes, involves him getting ready for his big interview with Nicolae Carpathia. Chaim Rosenzweig (who in addition to being a botanist and an electromagetismologist moonlights as a booking agent) has scheduled the interview for sometime after midnight:

“He has several interviews, mostly with television people, and then he will be live on ABC’s Nightline with Wallace Theodore. Following that, he will return to his hotel and will be happy to give you an uninterrupted half hour.”

So Buck’s “exclusive” follows “several interviews” and requires him to show up at Nicolae’s hotel room late at night. This is the sort of thing that gets Hattie in trouble later on. I also can’t help but wonder if Ted Koppel’s absence on Nightline is meant to suggest that he was among the disappeared. (And what’s with his replacement’s name? Is his co-host “June Ward”?)

He heads home to change out of his “George Oreskovich” costume (i.e., his baseball cap) and to shave and shower for the first time since his return to America. Steve Plank tags along to help him get ready, which makes him seem less like Buck’s editor and boss and more like Duckie in Pretty in Pink.

They don’t discuss Carpathia’s “electromagnetism” theory of the disappearances — even though just a few days ago Steve gave Buck the assignment of writing a feature-length cover story exploring just that topic. Nor do they discuss how it is that either of them still has a job when they haven’t produced an issue of Global Weekly in more than a week.

Instead, they talk about the international banking conspiracy led by Jonathan Stonagal and about Carpathia’s possible role in it. To be fair, it’s been less than 48 hours since Buck narrowly escaped a car bombing due to his investigation of this conspiracy, so it seems reasonable to me that this topic would be something Buck would want to discuss. (Laura Bush would disagree with me on that point — she would likely view this as another example of journalists’ biased preoccupation with “the one bombing a day that discourages everybody.”)

Buck’s investigation of this conspiracy is the one storyline so far in Left Behind that doesn’t directly involve events from the Bible Prophecy Checklist. The idea of powerful international bankers secretly plotting behind closed doors goes along with the fears of a coming One World Government and the Mark of the Beast, so this subplot isn’t much of a departure. But unlike Carpathia, these nefarious bankers don’t correspond to supposedly biblical characters from the premillennial dispensationalist timeline. Since that timeline drives the plot of this book, it’s hard to know what to make of it when we’re told that, after his press conference, Carpathia “was seen in the company of Jonathan Stonagal.”

Stonagal isn’t the Beast, or the False Prophet, or the Whore of Babylon, so what’s he doing here in the pages of Left Behind?

Mainly this subplot seems to exist so that we can see Buck playing the part of the Intrepid Reporter.

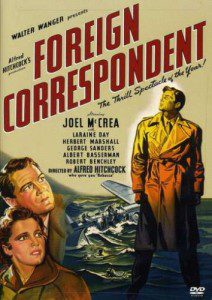

It’s the idea of the reporter as action hero — half detective, half super-spy. (Think Joel McCrea in Foreign Correspondent.) So we get many of the stock scenes from Intrepid Reporter movies. Buck receives a cryptic answering machine message and jets off to London to meet Dirk, his secretive inside source, only to find that Dirk is dead. It’s an apparent suicide, but the Intrepid Reporter suspects foul play — that Dirk was killed because he Knew Too Much. This is confirmed by the policeman who warns Buck to just drop it if he knows what’s good for him. The policeman tells our Intrepid Reporter that Dirk was killed by Joshua Todd-Cothran, the outwardly respectable head of the London Stock Exchange (think Herbert Marshall in Foreign Correspondent) who secretly controls Scotland Yard while plotting “some clandestine thing” with international banker Jonathan Stonagal. And then the policeman is killed, the victim of a car bomb intended for the Intrepid Reporter himself because he’s Getting Too Close.

Steve Plank and Buck Williams spend the next three pages discussing this conspiracy:

“But, Steve, you have to agree it’s likely that Dirk Burton was murdered because he got too close to Todd-Cothran’s secret connections with Stonagal’s international group. If they wipe out people they see as their enemies — even friends of their enemies like Alan Tompkins and I were — where will they stop?”

And here, abruptly, Buck ceases to play the part of the Intrepid Reporter. In the standard version, this would be where the IR and his editor discuss whether they have enough evidence to go public with the story (which, usually, they don’t, necessitating the elaborate set piece of the movie’s final act). But neither Buck nor Steve seems to remember that they’re in the journalism business. Neither of them recalls that the best weapon against shadowy conspiracies is the bright light of public exposure. It never occurs to either of these Woodward and Bernstein wanna-bes that the head of the London Stock Exchange killing a policeman might constitute news. When it comes to actually reporting on what he has learned, our Intrepid Reporter turns out to be extremely, well, trepid.

The bigger problem with all of this is that we never get even a hint of what “clandestine thing” it is that Stonagal and Mr. T-C are up to. We’re told there’s a conspiracy, but never what it is that they’re conspiring to do. There’s no maguffin.

The bigger problem with all of this is that we never get even a hint of what “clandestine thing” it is that Stonagal and Mr. T-C are up to. We’re told there’s a conspiracy, but never what it is that they’re conspiring to do. There’s no maguffin.

Dirk suggested that the Stonagal group has been advocating the shift to a single global currency, but that hasn’t been a secretive effort — it’s not even the sort of thing that could be done in secret. It’s kind of a dumb idea, but there’s nothing illegal about it. The only hint of illegal activity is when we’re told that Stonagal owns different banks in different countries. Arranging that seems like it would involve a bit of graft and corruption to get around foreign ownership regulations. Of course, this also seems like a reason for Stonagal to oppose any plan to consolidate currencies — the trading of which must be making him a fortune.

We learn later that Stonagal is pulling levers to orchestrate Carpathia’s election to the post of U.N. secretary-general, and it’s hinted darkly that this would make him the power behind the global throne. But we’re never told what he intended to do with this supposed influence.

What could one do? What would it mean if you did have a corrupt secretary-general in your pocket? I suppose you’d have the inside track to no-bid contracts for refugee resettlement. Maybe a slice of the lucrative Darfur-observer money machine. And you could guarantee that officials would look the other way as your criminal empire smuggled goods from northern Cyprus to southern Cyprus.

This plot only makes sense in the context of the authors’ peculiar understanding of the United Nations. According to this view, the U.N. secretary-general outranks the president of the United States. The president, after all, only rules over one country, while the secretary-general rules over the entire world. To LaHaye and Jenkins, Ban Ki-moon is not merely an international diplomat. He is the king of kings.