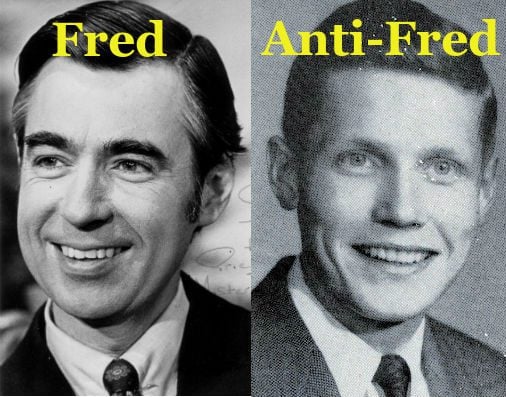

They shared a first name, and they were both ordained ministers, but other than that they were polar opposites. They present us with two very different possibilities — two choices, two options we all have. We can think of them as Fred and Anti-Fred.

The Rev. Fred Phelps is dying. And I find … I find that I don’t want to think about the Rev. Fred Phelps.

I’d rather think about the Rev. Fred Rogers — Mister Rogers. I’d rather re-read that old Tom Junod Esquire piece and all those other amazing stories about a kind and loving man who made everyone he encountered want to become kinder and more loving.

Fred Phelps, on the other hand, was a cruel, hateful man who made the world a little bit more cruel and a little bit more hateful every day.

Mister Rogers taught us that we’re all capable of being kind or of being cruel, of being loving or of being hateful:

Sometimes people are good

And they do just what they should.

But the very same people who are good sometimes

Are the very same people who are bad sometimes.

It’s funny, but it’s true.

It’s the same, isn’t it for me…

Isn’t it the same for you?

That was sort of Mister Rogers’ version of what Solzhenitsyn said about “the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being.” And I know that’s true. I’m sure that even Fred Rogers was “bad sometimes,” and that even Fred Phelps was “good sometimes.” But it’s also true that habits are habit-forming, and eventually those habits become character and identity. So I’d guess that even Fred Rogers’ “bad sometimes” were better than Fred Phelps “good sometimes.”

If Fred Phelps dies today, or tomorrow, or a few days from now, I will be saddened that he passed away before he was able to recant and repent, before he was able to attempt to atone and to seek absolution from those he has harmed and hated over the years.

But mostly I won’t want to think about him.

So here, instead, is something else to think about. Another option — a different choice of direction leading to much better habits. Much better, I think, to spend our time thinking about Fred Rogers than to spend another moment thinking about Fred Phelps.

This is from Tom Junod’s Esquire profile, “Can You Say Hero?”:

ONCE UPON A TIME, there was a boy who didn’t like himself very much. It was not his fault. He was born with cerebral palsy. Cerebral palsy is something that happens to the brain. It means that you can think but sometimes can’t walk, or even talk. This boy had a very bad case of cerebral palsy, and when he was still a little boy, some of the people entrusted to take care of him took advantage of him instead and did things to him that made him think that he was a very bad little boy, because only a bad little boy would have to live with the things he had to live with. In fact, when the little boy grew up to be a teenager, he would get so mad at himself that he would hit himself, hard, with his own fists and tell his mother, on the computer he used for a mouth, that he didn’t want to live anymore, for he was sure that God didn’t like what was inside him any more than he did. He had always loved Mister Rogers, though, and now, even when he was fourteen years old, he watched the Neighborhood whenever it was on, and the boy’s mother sometimes thought that Mister Rogers was keeping her son alive. She and the boy lived together in a city in California, and although she wanted very much for her son to meet Mister Rogers, she knew that he was far too disabled to travel all the way to Pittsburgh, so she figured he would never meet his hero, until one day she learned through a special foundation designed to help children like her son that Mister Rogers was coming to California and that after he visited the gorilla named Koko, he was coming to meet her son.

At first, the boy was made very nervous by the thought that Mister Rogers was visiting him. He was so nervous, in fact, that when Mister Rogers did visit, he got mad at himself and began hating himself and hitting himself, and his mother had to take him to another room and talk to him. Mister Rogers didn’t leave, though. He wanted something from the boy, and Mister Rogers never leaves when he wants something from somebody. He just waited patiently, and when the boy came back, Mister Rogers talked to him, and then he made his request. He said, “I would like you to do something for me. Would you do something for me?” On his computer, the boy answered yes, of course, he would do anything for Mister Rogers, so then Mister Rogers said, “I would like you to pray for me. Will you pray for me?” And now the boy didn’t know how to respond. He was thunderstruck. Thunderstruck means that you can’t talk, because something has happened that’s as sudden and as miraculous and maybe as scary as a bolt of lightning, and all you can do is listen to the rumble. The boy was thunderstruck because nobody had ever asked him for something like that, ever. The boy had always been prayed for. The boy had always been the object of prayer, and now he was being asked to pray for Mister Rogers, and although at first he didn’t know if he could do it, he said he would, he said he’d try, and ever since then he keeps Mister Rogers in his prayers and doesn’t talk about wanting to die anymore, because he figures Mister Rogers is close to God, and if Mister Rogers likes him, that must mean God likes him, too.

As for Mister Rogers himself…well, he doesn’t look at the story in the same way that the boy did or that I did. In fact, when Mister Rogers first told me the story, I complimented him on being so smart—for knowing that asking the boy for his prayers would make the boy feel better about himself—and Mister Rogers responded by looking at me at first with puzzlement and then with surprise. “Oh, heavens no, Tom! I didn’t ask him for his prayers for him; I asked for me. I asked him because I think that anyone who has gone through challenges like that must be very close to God. I asked him because I wanted his intercession.”