“It’s a thin line ‘tween heaven and here.” — Bubbles

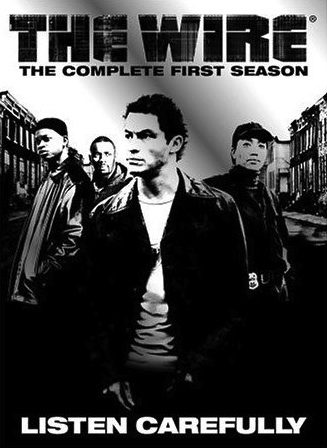

The Wire, David Simon’s gritty, haunting, novelistic series about Baltimore, ran for five seasons on HBO.

The first season set the stage by showing us the pain and violence of the city’s drug industry and how the police department, as an institution, was incapable of addressing the problem in any meaningful or effective way. Each subsequent season explored the same theme of institutional dysfunction, culpability and surrender, focusing on, in turn, labor and business, government, the schools, and the press. Year after year we saw each of these institutions crippled by the same problems, saw how they all were trapped and doomed by the same dynamics at play in the dysfunctional police department (and in the drug gangs).

The reality it showed was depressing. The honesty with which it examined and portrayed that reality was exhilarating.

The reality it showed was depressing. The honesty with which it examined and portrayed that reality was exhilarating.

I’m both relieved and disappointed that the show did not continue for a sixth season. That left another key institution spared from this same harsh examination. I’m thinking of the church — a powerful, visible, historically important institution in Baltimore and other great American cities.

I’m relieved that the church was never the central focus of a season of The Wire because it’s an institution that’s dear to me and one in which I have a personal stake. Season 5 was painful for me to watch as I was, at the time, working in the newsroom of a daily newspaper. The show’s portrayal of the press as impotent, incompetent and self-destructive was withering. It was cruelly precise and uncomfortably true-to-life. It was painful to see on the screen a distillation of the same wretched reality I was watching unfold slowly in real life — to see this once-great institution to which I was committed being exposed and examined in such an unforgivingly truthful light.

So part of me is grateful that another once-great institution to which I am committed — the church — escaped such a treatment.

But part of me is also sorely disappointed, because if the church is ever again to be a great institution, then such a brutally honest evaluation may be a necessary first step. It would be a painful process, but a positive one, to see the church’s institutional dysfunction and self-inflicted irrelevance portrayed and examined with the same ferocious eye that Simon turned on the Baltimore Police Department.

While never a central focus, the church is not wholly absent from the Baltimore of The Wire. Power-broking clergy flit around the edges of daily life in City Hall as powerful players in city politics. Black churches and Catholic churches appear as aging refuges for the weary — providing a measure of shelter from a world they are no longer able to influence. Such churches are a place for people like Omar Little’s grandmother, but they cannot reach people like Omar.

On a more positive note, there’s the Deacon — the nameless AME elder played by Melvin Williams, who pops up unexpectedly almost everywhere, gently nudging things in a more hopeful direction. And the best the church has to offer in The Wire is found in its basement, in the meetings where Steve Earle and Bubbles find salvation, redemption and rebirth.

I suppose the main reason The Wire didn’t focus more directly on the church is that the show’s creators hadn’t experienced it as a central, meaningful part of the fabric of the city as they knew it. David Simon was a former police reporter for the Baltimore Sun and his writing partner, Ed Burns, was a former Baltimore homicide detective. Their experience gave them an intimate knowledge of those institutions and their shortcomings in dealing with life on the city’s streets. Simon and Burns didn’t have that same level of experience with the churches of Baltimore.

That itself may be an indictment of the church as an institution: For the police, the beat reporters and the world of the streets, the church seems, at best, peripheral.

But it may also be that there was no need to revisit the theme of the show yet again in a sixth season. That theme and the clear pattern were so well established and richly developed over the first five years that it might have been redundant to sing the same song one more time. Just because the show never turned its focus toward the church doesn’t mean we don’t know what Season 6 of The Wire would have looked like. All the dysfunction and irrelevance of the Baltimore Police Department paralleled in the labor and business world, in City Hall, in the schools and in the press can be found in the institution of the church as well.

There’s no shortage of books calling for reforms of the institutional church. Some of those books follow much the same path Simon follows, tracing the way that institutions come to put their survival as institutions ahead of their mission and purpose — losing that mission and purpose along the way. Other books on the church just seem to be praying for a miracle — for a grand revival or great awakening, for the Holy Spirit to blow through like at Pentecost, miraculously bringing about the renewal of purpose we can’t seem to engineer or imagine ourselves.

If you’re interested in reviving or renewing the institutional church, then before consulting those many books, I recommend that you watch all five seasons of The Wire.

It shouldn’t be hard to draw the parallels and to make the analogies that will allow you to imagine exactly what Season 6 would look like, set in your own city or town. Look at the top brass of the BPD — the cronies and careerists and ladder-climbing, power-seeking incompetents obsessed with their own importance. Look at the mid-level leadership, the lieutenants and sergeants “gaming the stats” because they have more incentive to do that than to do the job itself. Look at Lester Freamon, natural police and a master of the craft, exiled to the Pawn Shop Unit for 13 years and four months because he did the job instead of playing the game. Look at Bunny Colvin, punished for the unpardonable sin of effectiveness.

Do any of these people look familiar? Do any of these stories remind you of anything? The characters, stories and themes of The Wire resonate in any institution. Not only in the church, but certainly there.

If there’s a problem with The Wire, it’s that it can be seen as counseling despair. It shows with perfect clarity that institutional change is desperately needed, but it also shows just as clearly that such a necessary transformation is close to impossible. The Wire offers a grave diagnosis and provides little in the way of a prescription.

But there’s a big difference between impossible and close to impossible. If transformation of broken institutions is only close to impossible, then it may prove to be very, very hard, but it still can be done.