In a post last week — “You might be an evangelical …” — I touched on some of the esoterica of the evangelical subculture. Much of that post was inside-baseball, jargon and references some readers (maybe the luckier ones) found a bit bewildering. Such as this, for example:

If you think the phrase “a witnessing tool” refers to something that’s good to have rather than someone it’s bad to be, then you might be an evangelical.

“What is a ‘witnessing tool’?” I am asked.

Well, it’s a tool for witnessing. OK, see, we evangelicals learn from a very young age that we have a duty to evangelize — to share the gospel of salvation with everyone we know and everyone we meet. Everyone. All the time. “Be a missionary ev’ry day,” we sang in Sunday school. “Tell the world that Jesus is the way …” This is what we call “witnessing.”

Maybe you’ve witnessed witnessing from the other side, when some acquaintance or stranger, friend or relative has asked you what would happen if you were to walk outside this very day and get hit by the Hypothetical Bus. Would you go to Heaven or would you go to Hell?

Maybe you’ve witnessed witnessing from the other side, when some acquaintance or stranger, friend or relative has asked you what would happen if you were to walk outside this very day and get hit by the Hypothetical Bus. Would you go to Heaven or would you go to Hell?

The Hypothetical Bus features prominently not just in witnessing, but in sermons reinforcing the solemn duty to witness to everyone we meet. What if that stranger next to you in line at the supermarket walks out to her car and is killed by the Hypothetical Bus right there in the parking lot? (The driver of the HB is a reckless menace who should have lost his license years ago.) You could have told her about Jesus, but now it’s too late and she’s suffering in Hell for eternity and it’s your fault.

That duty can be a heavy burden hard to bear. If you hear that sermon week after week for years, you’ll feel the weight of that urgent and never-ending responsibility to try to rescue these strangers, co-workers, friends, relatives, etc.

But that urgency doesn’t make the task itself any easier. Witnessing, as we’re taught and urged to do it seems awkward and unnatural and never seems to go as planned. For all of the emphasis on the constant duty to witness, most evangelicals remain ill-prepared to do it. They don’t know how to start such a conversation or to steer a conversation in that direction. They’ve got a vague outline of a formula or script for how this is supposed to work, but every time they try to follow it, the person they’re talking to takes some turn that the script didn’t anticipate and they find themselves lost and unable to improv the scene from there.

But that urgency doesn’t make the task itself any easier. Witnessing, as we’re taught and urged to do it seems awkward and unnatural and never seems to go as planned. For all of the emphasis on the constant duty to witness, most evangelicals remain ill-prepared to do it. They don’t know how to start such a conversation or to steer a conversation in that direction. They’ve got a vague outline of a formula or script for how this is supposed to work, but every time they try to follow it, the person they’re talking to takes some turn that the script didn’t anticipate and they find themselves lost and unable to improv the scene from there.

And so, out of desperation, they may turn to “witnessing tools” for help. A witnessing tool is any gimmick, usually something visual, that might help to start a conversation with strangers or to steer others into talking about Jesus.

It could be something like the buttons and billboards of the “I Found It” campaign, a massive effort organized by Campus Crusade — or “Cru,” as it’s now called — in the 1970s. But usually it’s less formal — a T-shirt with some famous corporate logo reworked into a logo for Jesus, or an eye-catching piece of sectarian jewelry, or a tattoo — anything that might conceivably spur a conversation that might provide the chance to rescue some poor soul from God. I mean, that is, to rescue them from God’s wrath and punishment in Hell (which is somehow different, I’m told).

The largest witnessing tool I ever saw was a 9-foot-tall wooden cross being carried by a guy on the shoulder of the highway. This was what he did. It was, apparently, all he did — wandering the highways of America as a mendicant evangelist.

The largest witnessing tool I ever saw was a 9-foot-tall wooden cross being carried by a guy on the shoulder of the highway. This was what he did. It was, apparently, all he did — wandering the highways of America as a mendicant evangelist.

I had lunch with the guy at a truck stop and came away both impressed by his quixotic devotion and worried about him, out there on his own without a faithful Sancho Panza to protect him. He was earnest and guileless — a holy fool, and to this day I’m not sure which of those words deserves the greater emphasis.

But what ever else was true of him, he had found a witnessing tool that worked. When you met that guy, even for five minutes, you couldn’t not talk about his giant cross. Everyone knew where that conversation was bound to go, but even those who would’ve preferred not to find themselves being witnessed to/at couldn’t help it. Even though you already know what his answer will be, when you meet a guy carrying a heavy, 9-foot-tall wooden cross, “What’s with the giant cross?” becomes an inescapable, irresistible question.

Please don’t take this as my advising you to take to the highways with a giant wooden cross. I think that gimmicky witnessing tools are a bad idea. I believe Christians are called to be witnesses and to bear witness, rather than doing the kind of witness-ing we’re often taught. But for those who are intent on employing a witnessing tool, then I recommend a giant wooden cross. As gimmicks go, that’s a much more effective conversation-starter than a “Jesus Christ: He’s the Real Thing” T-shirt.

But even those awful T-shirts are more plausible as witnessing tools than the ever-popular car fish. The ichthys, or “Christian fish,” has long been a Christian symbol — although it originally may have been a fertility symbol, set vertically (with the resemblance to a fish being an ancient dirty joke). Today it can be found on the cars of millions of Christians as a way of telling the traffic behind them that the driver of the car they’re following is a Christian. (Or, as Stephen Colbert joked, “I like Jesus, but can’t spell.”)

Many of the people affixing Jesus-fish to their cars tell themselves that this, too, is a witnessing tool. I don’t understand how that’s supposed to work. I can’t imagine any likely scenario in which a car-fish could function as a witnessing tool. A fish or an evangelistic bumper sticker can’t serve as a conversation-starter with the driver of the car behind you because neither of you is really in a position to chat. You can communicate only via the crude semaphore of the highway — the horn, the high-beams, the wave, the hand, the finger — and that lacks an adequate vocabulary for communicating the gospel.

Many of the people affixing Jesus-fish to their cars tell themselves that this, too, is a witnessing tool. I don’t understand how that’s supposed to work. I can’t imagine any likely scenario in which a car-fish could function as a witnessing tool. A fish or an evangelistic bumper sticker can’t serve as a conversation-starter with the driver of the car behind you because neither of you is really in a position to chat. You can communicate only via the crude semaphore of the highway — the horn, the high-beams, the wave, the hand, the finger — and that lacks an adequate vocabulary for communicating the gospel.

I’m opposed to car-fish and Christian bumper stickers in principle. As a general rule, any one of us is more likely to create a negative impression than a positive one for the driver behind us. The light turns yellow and we have to decide, very quickly, whether to accelerate or brake. Either way, we risk annoying the person behind us. Race through the intersection with a Jesus-fish on your car and the driver behind you might think, “Oh, look, the Christian runs red lights.” Come to a stop and they might think, “Oh, great, I could’ve got through the light if I weren’t stuck behind this slowpoke Christian.” We’re all subject to moments of inattention behind the wheel and it seems wrong for Jesus to have the share the blame for our driving.

Mainly, though, car-fish aren’t really intended for witnessing. They’re not witnessing tools, they are tribal symbols. The Jesus-fish on a car is not an invitation, but a declaration of tribal allegiance. It’s a signal that the driver of this car is an “Us” rather than a “Them.” And that Us-Them symbolism has far more to do with conflict than with any attempt at conversion.

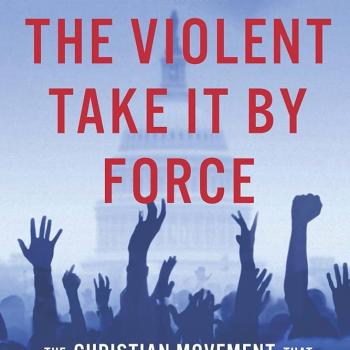

This is true as well of many of the other things we tell ourselves are “witnessing tools.” One one level, they may be intended as conversation-starters, but on another level they’re also intended as conversation-stoppers — as attempts to win some implied argument. They’re not really designed for evangelism. They’re just the graffiti and propaganda of the culture wars.

This is true as well of many of the other things we tell ourselves are “witnessing tools.” One one level, they may be intended as conversation-starters, but on another level they’re also intended as conversation-stoppers — as attempts to win some implied argument. They’re not really designed for evangelism. They’re just the graffiti and propaganda of the culture wars.

That plays into the political battles of those culture wars and the whole take-back-America-for-Jesus notion of Christian hegemony that has Michelle Bachmann and Rick Perry fighting over the evangelical voting bloc. But at its root, I think it’s a response to the pervasive and inescapable guilt from all those years of sermons about the necessity to constantly be “witnessing.”

All those people are going to Hell and it’s your fault because you’re not witnessing enough. You can never witness enough. You can never escape this relentless obligation and thus you can never escape this ever-present guilt.

Such insatiable guilt is bound to fester into resentment. One expression of that resentment is our culture-war politics. Another is the popularity of books like the Left Behind series, with its gleeful delight in the abominable fancy and its celebration of the destruction of the “unsaved.”

The T-shirt designs above are taken from this site and this one. Look through their online catalogues and you’ll find many that are — however tasteless, awkward or counter-productive — innocently intended to serve as “witnessing tools.” But you’ll also find some that only make sense as tribal symbols. And you’ll find many more that can’t in any way be explained by a desire to reach the unreached or to save the unsaved — T-shirts expressing a triumphalist mockery that can only be described as attacks on those unsaved and unreached reprobates, as volleys fired in the war of Us vs. Them.

The T-shirt designs above are taken from this site and this one. Look through their online catalogues and you’ll find many that are — however tasteless, awkward or counter-productive — innocently intended to serve as “witnessing tools.” But you’ll also find some that only make sense as tribal symbols. And you’ll find many more that can’t in any way be explained by a desire to reach the unreached or to save the unsaved — T-shirts expressing a triumphalist mockery that can only be described as attacks on those unsaved and unreached reprobates, as volleys fired in the war of Us vs. Them.

The witnessing tool T-shirts were intended as an expression of concern for the unsaved. The tribal and culture-war T-shirts are an expression of resentful contempt for them.

That resentment and contempt, I think, is in part a curdled form of what initially began as a kind of love. Love led to guilt and guilt led to resentment and resentment flowered into vicious contempt.

I think that downward cycle, which feeds on itself, becoming stronger over time, can help us to understand a great deal about the nasty tone of what many American evangelicals still strangely regard as “witnessing.” And I think it can also explain a great deal about our current politics and our increasingly stratified economy.