Thinking about the despair, fear and trauma of Harold Camping’s devotees leading up to and through and after his supposed Day of Judgment this weekend, I keep thinking back to a man I once knew. He was an old fundamentalist preacher and retired military chaplain with whom I spent several holidays years ago when I was briefly married to his granddaughter.

The old preacher bore more than a little resemblance to the farmer in Grant Wood’s “American Gothic.” That was a good word for his personality, too. Gothic. If Pat Conroy, Flannery O’Connor, Barbara Kingsolver and Stephen King got together to write their ultimate stern father/religious zealot/ominously dour character, they might have come up with something like the chaplain. He was a sullen and depressive, but volatile man who cast a long, dark shadow over the lives of his two daughters, never forgiving them for not being sons. He drove one into a lifetime of therapy and the other into a lifetime of denial.

He was not a man who invited fondness, but he was family, after all, and so we loved him. If that love tended to be more an expression of duty than of affection, it was also warmed by occasional bursts of pity. It was hard not to feel pity whenever he had one of his bouts of maudlin emotion and uncontrollable weeping. He was a lifelong teetotaler, but when these sudden moods struck him he became a sober version of a mawkish drunk, sobbing and proclaiming his deep love for strangers in the bar. The strangers in this case were his own daughters, grandchildren and family who would exchange nervous looks and do their best to comfort him as, one by one, we would each make and repeat the promise he would beg us to make him.

“Don’t worry,” we would say, “you won’t be cremated. I promise. No, no, it’s OK. We won’t let that happen to you.”

The old preacher, you see, was a “Bible prophecy” enthusiast. He was a devotee of John Hagee, and of TV host Jack Van Impe and of anyone connected with Dallas Theological Seminary and its premillennial dispensationalist obsession with the End Times as interpreted through their crazy-quilt re-editing of Revelation and Daniel. He eagerly devoured all of their books and many other, even stranger works — self-published volumes of cryptic numerology, cramped and fevered tomes identifying the Antichrist as Kruschev or Kissinger or Ted Kennedy.

And somewhere, in one of those fringe-of-the-fringe books, he had encountered and adopted the idea that cremation rendered a body immune to resurrection. When the last trump shall sound and the dead in Christ are raised, when the sea gives up its dead and every grave is opened, he believed, those who have been cremated would remain only ashes.

The idea fit somehow with his stubborn illiteralist approach to the Bible. Those verses that spoke of the graves being opened or of “those that are asleep” being raised from their graves said nothing about those who had no graves but whose ashes had been, instead, scattered to the winds. And the idea was fortified by whatever author or radio preacher promoted it with a diatribe against cremation as a supposedly unholy, “pagan” practice — as though it were some sort of evil anti-sacrament that trumped every means of grace. I think he may have identified cremation, somehow, as the supposed “unforgivable sin,” a blasphemy against the Holy Spirit.

And it terrified him. Constantly. He expected the Rapture to occur any day, any moment, but he also knew that he was an old man and that, if the End tarried another year or five or ten, he might well die before Jesus came like a thief in the night. Once he was dead, he would be powerless to prevent the living from having his body cremated and if that happened he would be eternally separated from God. This is what he believed and what he lived in fear of every day.

Witnessing that terror and hopeless fear, seeing the suffering that it brought, I stopped thinking of his “Bible prophecy” obsession as a kooky, but mostly harmless set of beliefs. I began to realize that it was a framework that burdened its followers with the inevitability of disappointment, false hope, denial and an inconsolable fear. Its adherents were its victims. There were other victims, too, but its main damage was wrought in the lives of those who most believed it.

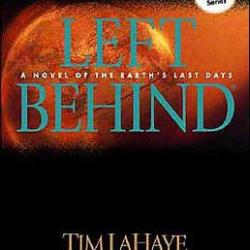

Again, this business about cremation isn’t taught by the “mainstream” Bible prophecy salesmen. This is not something that Tim LaHaye or Hagee or Hal Lindsay believes. But their teachings offer a host of other, similar ideas just as baseless and just as cruelly oppressive.

Talk to anyone who grew up in a Rapture-believing church or family and they will tell you stories about panic-inducing moments when they found themselves suddenly alone and feared that everyone else had been raptured while they had been rejected by God. This guy thinks that’s funny, but it’s actually traumatic. That’s why no one forgets the horror of such moments. Laughing at one’s own trauma can be transformational and healthy. Laughing at someone else’s trauma is just cruel.

That fear and trauma, we were sometimes told, was a good thing. It was a holy terror — a reminder to make certain that we prayed the right prayers and felt the right feelings to ensure that we would not be among those left behind. This is what they thought the scriptures meant when they spoke of “the fear of the Lord” — the powerless terror of the child of an abusive parent.

And that terror is what Harold Camping and his followers are feeling now. And it is what they will be feeling again Saturday evening, after that terror and despair first abates, then metastasizes in the realization that the world has not ended and that they are not the righteous remnant they staked their identities on being.

Fortunately, Camping is not as widely influential as LaHaye, so we’re talking about only thousands of followers, not millions. But that’s thousands of people, thousands of families experiencing one kind of trauma now and due for another, existential, shaken-to-the-core trauma come Saturday. That some of this trauma is self-inflicted or that, like most victims of con-artists, they are partially complicit in their own undoing doesn’t change the fact that we’re still talking about thousands of people in pain, fear and despair.

It may take a while to help them pick up all the pieces after the great earthquake that never happens, and I’m not even sure how to help them. But I want to try — partly out of pity, partly out of duty, but ultimately out of love because, after all, they’re family.