Tribulation Force, pp. 336-346

Buck and Tsion Ben-Judah are headed back to the Western Wall to talk to the Two Witnesses whom the authors identify, following one tradition, as Moses and Elijah. Yes, that Moses and Elijah.

Most authors would balk at the difficulty of enlisting two such figures as characters in a novel. It's one thing to write a screenplay for The Ten Commandments, supplying dialogue for Moses in a retelling of the biblical story, but it takes a lot more chutzpah to lift Moses out of that story and insert him into your own for a cameo appearance alongside Buck Williams. Tim LaHaye and Jerry Jenkins have the audacity to try this, I think, because they don't realize that it even involves audacity. Fools rush in where good writers fear to tread.

The sudden presence in our story of Moses and Elijah raises all sorts of questions and possibilities. The timeline in these books is hard to follow, but I believe it's some time in March — the Event was a month ago and at the time there was basketball, but no football or baseball, so March seems a good guess — which means Passover is coming up. That would be interesting with these two. Do you still leave an empty seat at the Seder for Elijah if Elijah himself is actually there? And what would Moses make of that tradition? He was at the very first Passover, and nobody there had ever heard of Elijah.

Pondering such questions for some reason leads me to start picturing Mel Brooks as Moishe and Jerry Stiller as Eli. That makes this section of the book much more entertaining.

"We should go preach by the temple."

"OK. What's a temple?"

"It's like your tabernacle, but made of stone."

"Stone? How are we supposed to carry it if it's made out of stone?"

Nothing I can imagine Mel and Jerry saying is sillier than what we actually get here in Tribulation Force — a theological mash-up that makes little sense and just gets more confused as the authors decide to have Moses and Elijah recite the Gospel of John, with Tsion playing the role of Nicodemus.

But I'm getting ahead of our text here, so let's catch up. As Buck prepares for his appointment with the witnesses he:

… reminded himself to check with Jim Borland and others at the Weekly to be sure photographers were at least getting long shots of the two when they preached.

Borland, you'll recall, is the religion editor with whom Buck traded stories. So after begging and manipulating his colleague into letting Buck take charge of the story about the two preachers, Buck still assumes that Borland is handling all the photo assignments and other details for him. Buck must be a joy to work with.

Rayford, meanwhile, is still sitting around watching television. This is such a huge part of the Tribulation Force's activities that I think the authors would have saved us a great deal of time if they had made Buck a reporter for CNN and Rayford his producer.

CNN is reporting on a new piece of U.S. legislation that would allow for a total media monopoly. The authors' description of this legislation makes it clear that they don't really understand the legal barriers that exist to such a monopoly now, or entirely appreciate why those barriers are a Very Important Thing.

The surprising legislation allows a nonelected official and an international nonprofit organization unrestricted ownership of all forms of media and opens the door to the United Nations, soon to be known as Global Community, to purchase and control newspapers, magazines, radio, television, cable and satellite communications outlets.

I'm giving the authors a pass on not foreseeing the cell-phone revolution when they wrote this book in 1996, but it was really late in the game for them not to have yet noticed the Internet.

The "legislation" in question here seems to be something working its way through the U.S. Congress. That Congress, you'll remember, was rendered obsolete back in Book 1 of this series when Nicolae proclaimed his One World Government, establishing 10 princes to rule over its new divisions. But I guess nobody told Congress, so now they're busy dismantling FCC and FTC regulations to clear the path for Nicolae Carpathia's global media monopoly.

Oddly, Congress didn't feel compelled to act earlier when Nicolae declared his mandatory one-world religion — a measure that I'm pretty sure also runs afoul of existing U.S. law.

"The only limit will be the amount of capital available to Global Community, but the following media are among many rumored to be under consideration by a buyout team …"

The anchor drones on, listing every newspaper or media company Jenkins can think of.

Rayford sat on the edge of the bed and listened in disbelief. Nicolae Carpathia had done it — put himself in a position to control the news and thus control the minds of most of the people within his sphere of influence.

Rayford, unlike every journalist in this book not named "Cameron Williams," views this media monopoly as a Bad Thing. And of course it would be. But by recognizing this, the authors here stumble into a bit of ideological inconsistency. They have just revealed the contradictions inherent in their own political stance.

The Left Behind series is, among other things, a fictional argument for the antigovernment ideology of LaHaye's John Birch Society beliefs. Every government action, in LaHaye's view, is a step closer to Total Government — the coming one-world government of the Antichrist. Every environmental rule, every antitrust regulation, every law or ordinance that in any way restrains the complete and utter freedom of capital is, to LaHaye, socialistic and evil. For LaHaye, government = Antichrist.

Most of the time, in other words, LaHaye is arguing that the ideal situation — the ideal Christian, biblical situation — would be one in which the only limit on unrestrained capital is "the amount of capital available." But all of a sudden — contrary to everything we've read up to this point and contrary to everything Tim LaHaye has fought for, politically, for decades here in the real world — government rules and regulations seem to be a good thing. The Federal Trade Commission and Federal Communications Commission have to be swept aside in order for the Antichrist to rise to power.

Suddenly it's the Antichrist who is revealed as a champion of deregulation.

The authors don't seem to notice this sudden reversal and contradiction of all that they've been arguing before. That's a shame. Had they noticed, it might have made them start to consider whether an absolute stance against all government power — even limited, checked and balanced, democratically accountable government power — really makes sense for securing freedom if that same stance requires an absolute rejection of any and all limits on the power of wealth. It might have made them realize that LaHaye's reflexively antigovernment ideology is utterly impotent when it comes to securing human freedom, and utterly dependent on the benign intentions and actions of the very wealthy. It might have helped them to see that the ideology of the John Birch Society is really very silly indeed.

But they didn't notice that.

Buck and Tsion return to the Western Wall, where:

Remains of the would-be assassin had been removed, and the local military commander told the news media that he and his charges were unable to take action "against two people who have no weapons, have touched no one, and who have themselves been attacked."

The local army, like the FTC, the FCC and the U.S. Congress, continues to operate independent of Nicolae's OWG. For a global dictator, he doesn't yet seem very global or very dictatorial.

Buck and Tsion cautiously make their way toward their rendezvous with the fire-breathers:

The rabbi walked with his hands clasped in front of him, and Buck couldn't help doing a double take when he noticed. It seemed an unusually pious and almost showy gesture — particularly because Ben-Judah had seemed disarmingly humble for one holding such a lofty position in religious academia.

On my way to work, I drive past the highest point in Delaware. In that sentence "the highest point" is qualified and recalibrated by the phrase "in Delaware" in much the same way that in Jenkins' sentence "such a lofty position" is qualified and recalibrated by the phrase "in religious academia."

"I am walking in a traditional position of deference and conciliation," the rabbi explained. "I want no mistakes, no misunderstanding. It is important to our safety that these men know we come in humility and curiosity. We mean them no harm."

That's the smartest thing this genius-scholar has said yet.

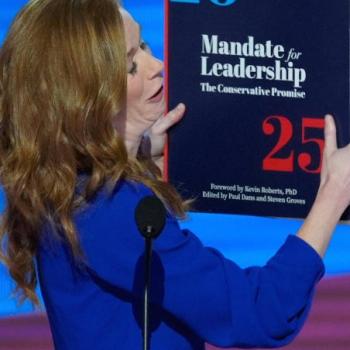

When Buck and Ben-Judah were within about 15 feet of the fence, one of the witnesses help up a hand, and they stopped. He spoke, not at the top of his voice, as Buck had always heard him before, but still in a sonorous tone. "We will approach and introduce ourselves," he said. The two men walked slowly and stood just outside the iron bars. "Call me Eli," he said. "And this is Moishe."

"English?" Buck whispered.

"Hebrew," Ben-Judah responded.

"Silence!" Eli said.

And now all I can think of is, "There are some who call me … Tim." But after reading this chapter both ways, I still think it works better with Brooks and Stiller than with Palin and Chapman, so I'm sticking with the first one.

Buck and Tsion come a bit closer and Buck notes that, "The scent of ashes, as from a recent fire, hung about them," which shouldn't be that surprising.

Suddenly Moishe stepped close and put his bearded face between the bars. He stared at the rabbi with hooded eyes and sweat-streaked face. … Moishe spoke as if he had just thought of something very interesting, but the words were familiar to Buck.

"Many years ago, there was of man of the Pharisees named Nicodemus, a ruler of the Jews. Like you, this man came to Jesus by night."

Rabbi Ben-Judah whispered, "Eli and Moishe, we know that you come from God; for no one can do these signs that you do unless God is with him."

And they're off, reciting to one another most of the third chapter of John's Gospel, because what else would any good rabbi want to talk about if granted the supernatural opportunity to converse with Moses himself?

I think I understand why the authors decided on this approach. They needed to have Moses and Elijah say deep and profound things that would seem worthy of Moses and Elijah, and they wanted those deep and profound things to be unassailably biblical, so having the Two Witnesses recite directly from the Bible seems like the safest way of handling this scene. But the question then becomes what biblical passage to have them recite, and L&J settled on that old standby of John 3:16.

Great verse, great chapter, great story — but a story and a passage that make no sense at all here, in this context, with these characters.

John 3 tells of Jesus' meeting with Nicodemus — a first-century Pharisee. Nicodemus, like Tsion, was a devout Jew who longed for and anticipated the coming of the Messiah. The Messiah, Nicodemus believed, would restore the people from exile and rebuild the Temple — properly, not like Herod did — establishing the reign of righteousness in Zion through which all the world would be saved.

Now, while I'm sure that Nicodemus would have been humbled by the privilege of speaking directly with Moses and/or Elijah, neither of them really had much to say about the topics that concerned him most. Moses provides a type of the Messiah, but he was too busy liberating his people and leading them to the Promised Land to take the time to dream of a future messianic figure who would one day liberate the people and lead them to the Promised Land. Moses didn't spend much time foretelling of a coming new Moses. Elijah, likewise, had little to say about a coming Messiah who would restore the line of David because the line of David was still in charge and was actually, in Elijah's time, making a royal pain of itself. And Elijah had nothing at all to say about the restoration of the people from exile because the exile hadn't happened yet.

My point here is that Moses and Elijah are just a bad fit for this conversation with Tsion/Nicodemus and a bad fit overall for the whole "Messiah Messiah Messiah" message that L&J have given them to proclaim. Isaiah or any of the post-exilic prophets would have made more sense here — the prophets who actually had a lot to say about the themes that most concerned Nicodemus and Tsion and the authors.

So why opt for these two unlikely and inappropriate characters? As I mentioned above, there's a long tradition of identifying Moses and Elijah as the unnamed, unidentified in the text, Two Witnesses of Revelation 11. If we consider the ideas behind that tradition, we'll find that L&J don't seem to understand fully what it says about the meaning of Revelation 11.

Moses and Elijah suggest themselves as potential candidates for the witnesses due partly to their brief appearance in the Synoptic Gospels in the story of Jesus' "transfiguration" (here is Mark's version). It's not hard to get a basic sense of what's going on in that story, with the lawgiver and the great prophet portrayed as giving their blessing to Jesus. I suppose this symbolism is part of why L&J have enlisted these same two figures here.

But the transfiguration story isn't the only reason for the tradition equating the Two Witnesses with Moses and Elijah. "Bible prophecy" writers like LaHaye will also point out that the deeds ascribed to the witnesses have a similar m.o. to stories about Moses and Elijah. The witnesses, Revelation says, will be able to turn water into blood "and to strike the earth with every kind of plague" — just like Moses did in Egypt. And the fire-breathing thing is kinda sorta reminiscent of Elijah's calling down fire in his showdown with the priests of Baal.

But what LaHaye and all his fellow premillennial dispensationalist "prophecy scholars" fail to consider is why Moses and Elijah did such things. Moses overthrew Pharaoh and liberated the people. Elijah held the evil King Ahab accountable. The traditional suggestion that the witnesses are Moses and Elijah is because they are archetypal examples of the role that the witnesses play in John's Apocalypse — fearless denouncers and opposers of the evil empire. The tradition that identifies those witnesses as Moses and Elijah does so because it sees this as the grand theme of Revelation — resistance to and triumph over the Beastly empire.

LaHaye doesn't think that is what Revelation is all about. He thinks it's entirely "prophetic" — by which he means something utterly different than and incompatible with the ministry of the prophet Elijah. For LaHaye it's all about prediction, prognostication, foretelling and fortune-telling.

So the presence of Moses and Elijah here undermines LaHaye's whole approach to the book of Revelation.

Settling on Moses and Elijah also gives an added bit of anti-Semitic piquancy to LaHaye's mangling of Jesus' conversation with Nicodemus. After beginning with direct quotations from the book of John (the miraculous simultaneous translation Buck is hearing is, curiously, in the New King James Version), the dialogue shifts to include words taken from John 3, but rearranged into a kind of catechism in which Moses and Elijah seem to be quizzing the rabbi on the particular depravity of Jews.

Suddenly the rabbi became animated. He gestured broadly, raising his hands and spreading them wide. As if in some play or recital, he set the witnesses up for their next response. "And what," he said, "is the condemnation?"

The two answered in unison. "That the Light has already come into the world."

"And how did men miss it?"

"Men loved darkness rather than light."

"Why?"

"Because their deeds were evil."

"God forgive us," the rabbi said.

I suppose it's possible to read this as a general commentary on the "condemnation" of all of sinful humanity, but given the context of B-J's Messiah research project and TV special, that last bit really seems to me like a nasty example of the stock "Bible prophecy" riff about the particular fate of those evil, Christ-denying Jews.

"Thus ends our message," the two witnesses say, and when Buck and Tsion protest that they have more questions:

"No more," they said in unison, neither opening his mouth.

And now I'm picturing the witnesses as a pair of Talosians from that old Star Trek episode. They offer Buck and the rabbi a telepathic and pointedly non-Jewish benediction:

"We wish you God's blessing, the peace of Jesus Christ, and the presence of the Holy Spirit."

And they part. Ben-Judah is too shaken by what he's just seen to talk about it, so Buck is left to silently ponder whether this all meant that Rabbi Tsion Ben-Judah would accept Jesus Christ as his personal Lord and Gentile Savior:

What he did not know was how the rabbi interpreted all this. Could he have missed the message of the conversation between Nicodemus and Jesus when he had read it from the Scriptures, and again now when he had been part of its re-creation? Buck certainly hadn't missed it.

But Ben-Judah isn't talking. He deposits Buck back in the car and then wanders off without speaking as his driver returns Buck to his hotel and to its many, many telephones.