Tribulation Force, pp. 281-289

To create is to love.

Artists know this. To paint a picture, sing a song, play a part or write a story is an act of love. This is a truth expressed on the very first page of the Bible, a refrain in the creation story of the first chapter of Genesis. One expects a creation story to be a hymn of praise to the creator, but Genesis turns that upside down, presenting the story as a hymn of praise by the creator to the creation. As God is portrayed bringing into being every piece of the world, the story repeats the refrain, "and God saw that it was good."

To create is to love is also a truth expressed in the second creation story in Genesis, in the remix that follows the first one. That second story — taking place in a single day instead of seven — portrays a hands-on creator forming humanity out of the dust of the earth and breathing life into our nostrils. It's a lovely image of the intimate caring of an artist at work.

I heard a more down-to-earth example of this same truth recently in an NPR interview with Frank Langella originally recorded shortly after Frost/Nixon came out. Langella described a conversation he had with Anthony Hopkins in which the two actors reminisced fondly about their old friend Richard Nixon. I don't know if either man ever met Nixon in person, but they had both brought him to life on film and thus, inescapably, they had come to love him. That didn't mean they admired everything about him or that they overlooked his many flaws — far from it — but they had come to know him intimately and thus to understand him. And to understand is to forgive.

To create is to love, but apparently not always. Tim LaHaye and Jerry Jenkins do not love Hattie Durham. They despise their creation. Their contempt for her and disgust with her is tangible in every scene she appears in.

I think the authors expect their readers to share in this contempt, but that's not how this works. When an artist creates a character that the artist does not love, readers or audience members don't come to dislike that character, they come to dislike the artist. It is the writer — or actor, or painter — who reveals himself as unlovely. The character just becomes an expression of that unloveliness.

When one encounters a character like Hattie, a creation unloved by her creators, one has to wonder why she came to be at all. Creation takes work, so why put in all that effort for something you do not love?

When we see what becomes of poor Hatties in these books — what awful things are done to her first by Rayford, then by Nicolae, and throughout by the authors themselves — an answer begins to suggest itself. Hattie Durham was created to suffer and then to be destroyed. That is why she was made. Her creators sought an object to punish and to destroy and so Hattie Durham was brought into being.

"Bad Theology produces Bad Writing" has been one of the recurring themes of our survey of these books. We've seen, time and again, how that plays out in creating a nonsensical plot driven by motiveless characters caught in a disjointed series of arbitrary, implausible and inexplicable events, but it goes deeper than that. LaHaye and Jenkins have created their world in imitation of the way they imagine God has created this world. It is a world, they believe, that was created to be punished, to suffer and then to be destroyed and replaced. That is its purpose, the reason it was made.

As always, Bad Theology produces Bad Writing. (And vice versa.)

What this capriciously cruel notion of creation means in practical terms is that passages like this one in Chapter 13 of Tribulation Force are almost unbearable. Any reader who doesn't share the authors' contempt for Hattie — shaped by that same cruel notion of the creator — will find this difficult to get through. You wind up reading such passages trying to defend her, to take her side, even though the authors haven't provided any basis for you to do that.

That problem is compounded in this particular Hattie section by Jenkins' attempt here to use her as the voice of exposition. For Jenkins, exposition usually involves an artificial-seeming conversation in which one character who knows what's going on explains it all to another character who doesn't. That makes the latter seem exceptionally slow-witted and dim. The latter character, in this case, being Rayford Steele.

Rayford spends five pages here saying little more than variations of "I don't understand what you're telling me, please repeat with additional detail." It's almost that explicit. Here are just a few lines from Rayford's side of this conversation:

"What does that mean?"

"Tell me what the point was."

"Go on."

"OK."

"I'm just saying I follow you, though I'm not sure I really do."

"Still with you, I think."

"I've got lots of questions, Hattie."

Rayford slumped and sighed, "Hattie, for the love of all things sacred, just tell me what's going on."

Five whole pages of that. If he were more cheerful, he'd come across like the host of an infomercial — "Amazing, Billy — such an incredible product must sell for hundreds of dollars, right?" But he's so surly and impatient throughout that he just comes across as angrily uncomprehending.

Jenkins is also in a bit of a bind here because this technique of one-sided expository conversation also tends to make the other character — the one who knows what's going on — seem smarter and more competent. And Jenkins despises Hattie too much to allow her to seem smart or competent. His solution here is to portray Hattie as barely capable of communicating the simplest facts, extending and belaboring the whole process. Working one's way through eight pages of such a conversation is not a pleasant experience.

Further miring all of this down is the fact that everything being discussed and explained here has already been discussed and explained earlier. Readers already know all of this. Rayford already knows all of this. He already knows the answers to the questions he's asking. He already knows the information he whiningly demands she tell him. He's already figured out "about the flowers and the candy" and he already knows about Nicolae's plans to commandeer Air Force One as his private jet.

Here for example is Rayford some 60 pages earlier on pg. 224:

Being known as the pilot of Air Force One — or even Global Community One — for seven years was simply not on his wish list.

Not only did he already know that Air Force One was going to become Nicolae's personal plane, he even already knew that it would come to be called "Global Community One" — several chapters before Nicolae supposedly announced the "Global Community" brand name.

As for the flowers and candy, Rayford already knew about the imaginary stalker scheme because his Pan-Continental boss, Leonard Gustafson, let that slip back on pg. 248:

"I mean, Rayford, you'd never forgive yourself if something happened to that little girl and you had a chance to get her away from whoever is threatening her. … I'm talking about the roses, or whatever the bouquet was. … Sometimes a person has a reason to leave … if your daughter is being hassled by someone."

Rayford finally put all that together about 30 pages ago, after Chloe received the candies, the tell-tale "Windmill Mints from Holman Meadows."

The only new thing we learn in these eight agonizing pages is that Hattie hadn't intended to tip her hand quite so obviously:

"Hattie, did you think I wouldn't put two and two together when you sent Chloe's favorite mints, available only at Holman Meadows in New York?"

"Hmph," she said, "maybe that wasn't too swift."

This illustrates Nicolae Carpathia's main flaw thus far in the Antichrist business: staffing.

The man is trying to run a global evil empire with a four-person crew consisting of himself, Hattie, Chaim and Steve. That's just not going to work. He needs minions. To go global, he'll need millions of them. If you trying to become the evil totalitarian ruler of the entire planet, you're going to need minions and lackeys and secret police in every corner of every village of the globe. Mind mojo notwithstanding, you just can't expect to pull this off with only a press secretary, a botanist and your girlfriend working for you.

The whole fictional-stalker ruse was ill-conceived from the outset, but if Nicolae had any hope of making it work he needed to have Chloe followed by a team of minions who could then supply unnervingly personal details in the notes accompanying the anonymous gifts. Flowers with an unsigned card aren't creepy enough to convince somebody to relocate for the safety of his family. But imagine that Chloe spills coffee on her blouse one morning then, later that day, receives an unsigned package containing a brand-new, identical blouse — perfectly tailored — with a note reading, "You will be mine."

In Nicolae's defense, this clumsily conceived and executed scheme is part of his attempt to expand his staff. He has spent most of this book trying to manipulate Rayford and Buck into working for him. Should he succeed, that would be a statistically significant 50-percent increase in the size of his Antichrist staff. But a new pilot and a midwestern newspaper editor aren't the most urgent vacancies facing his organization, and no two — or two thousand, or two million — new hires could be nearly enough to begin the task of global domination he has before him.

The truth of the matter — and I find this reassuring — is that no totalitarian regime can ever be adequately staffed. No such evil regime can ever hope to employ enough secret police to monitor every thought and action of every person at all times. Even with unlimited resources to hire such police, the regime would in turn need more monitors to monitor them, and still another layer of monitors to monitor those monitors, ad absurdum.

Totalitarianism of the sort that Nicolae is attempting simply can't be done without a large degree of cooperation. The only way to make it work is to convince and coerce your subjects into monitoring each other. You need them willing and eager to inform on any suspicious or insubordinate speech or behavior. Create a context in which that becomes the norm and you can get by with some manageable number of secret police — though you'll still need far, far more of them than Nicolae has yet even contemplated hiring.

Ensuring this kind of collaborative repression usually involves a system of rewards and punishments. The rewards don't need to be much — increased chocolate rations for those who loyally betray their neighbors and relatives (all of this is more manageable if you're dealing with a desperately impoverished population, the closer to the bottom of Maslow's pyramid the better). The punishments can be random and arbitrary, just as long as they're flamboyantly severe.

It's old-fashioned divide and conquer. You're not so much trying to make people fear your secret police as you are trying to make them fear the neighbors who might turn them in to those secret police. Create a context in which the safest course of action for any individual as an individual is to provide a terrified assistance to their own subjugation and most people will abandon any consideration of the greater good in order to do what is safest and easiest for them individually.

The problem for Nicolae, and for any other would-be totalitarian despot, is that most people is not all people. And not only is resistance inevitable, it's also contagious. And when non-cooperation reaches a tipping point, your absolute rule ceases to be sustainable.

But nobody ever said that being the Antichrist was going to be easy. If Nicolae wants to succeed in his chosen vocation then he needs to commit himself to learning the craft of Antichristing. He has so much to learn and so little time to learn it all that I'd recommend a crash-course of study at the Albert Einstein Institution. Gene Sharp knows more about how repression works than anybody else on the planet and he might be able to get Nicolae up to speed on the scope and demands of the job and on the time-tested Best Practices for totalitarian regimes.

This is why Sharp's research has been translated into so many different languages and why it is read with desperate urgency by every despotic government. Sadly for those despots, but happily for the rest of us, they're unable to find in Sharp's research the loopholes they're looking for. The inescapable lesson of all his studies is that antichrists and pharaohs may arise, but their efforts cannot be sustained in the long term — and not even in the short-term if their subjects refuse to cooperate.

Come to think of it, that's pretty much the same lesson conveyed in religious apocalyptic literature as well, unless one reads it through a distorting lens of the sort that Tim LaHaye attempts to provide.

The unbearable conversation between Hattie and Rayford ends with a return to LaHaye's Kill All Sheep theory of Bible prophecy.

According to LaHaye, the foremost responsibility of Christians is to be on guard against the coming Antichrist. Since that Antichrist, he says, will present himself as a wolf in sheep's clothing, LaHaye advises his readers to be wary of anything sheeplike. A vigilant shepherd, the authors insist, should kill all sheep on sight, just to be safe.

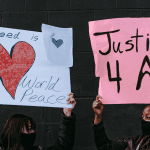

If someone comes along speaking of peace, unity, love or justice, that person might be just using those things as a mask for evil purposes, so presume they are guilty. If someone talks like Christ, they might really just be a lying Anti-Christ, so anything that smacks of loving your neighbor, or loving your enemy, or blessed are the poor or the peacemakers should be carefully avoided.

The Lamb's clothing that L&J bring up here involves what they present as an alarm-bell phrase: "the greater good."

"You told him I was a Christian."

"Sure, why not? You tell everyone else. I think he's a Christian, anyway."

"Nicolae Carpathia?"

"Of course! At least he lives by Christian principles. He's always concerned for the greater good. …"

For the authors, you see, "concerned for the greater good" is a clear signal of dangerous evil. For Tim LaHaye and Jerry Jenkins, the following clip from Wrath of Khan is a horrifying display of monstrous evil: "What do you think of my solution?"

Now of course it's true that the idea of "the greater good" can be abused and hijacked by malevolent people who are really intent on its opposite. That's no less true of "the greater good" than it is of "peace" or "love your enemy" or "blessed are the poor."

Cult leaders from Jim Jones to Chairman Mao have manipulated their followers through appeals to "the greater good." So have David Cameron and Alan Simpson. Johnny Knoxville regularly appeals to something like the notion of "the greater good" as a means of convincing his dearest friends to subject themselves to hilariously unspeakable torments. "Dulce et decorum est, Steve-O, now bend over."

And it's even true that we could guard against every such abusive usurping of the idea by simply rejecting the idea itself. Kill All Sheep. We could simply oppose every appeal to "the greater good" or the common good because it is an appeal to the greater good or the common good — which is what L&J are suggesting here by making this idea a hallmark of their Big Bad.

If we followed this advice, it would go a long way toward guarding against cults and communists. And taxes. And armies. And democracies, constitutions, rights, schools, libraries, schools, religious congregations, fire brigades, police forces, markets, roads, sewers, towns, neighbors and communities.

That seems like a lot to give up. So before I sign on with the authors' anti-greater-good political philosophy, I'd like to know what they intend as a replacement.