The Associated Press apparently frowns on bloggers linking to AP news articles and quoting the first paragraph in its entirety. I’m about to do just that. It’s unavoidable in this instance, since my whole point in linking to this AP story by Christopher S. Rugaber is to note that it’s inaccurate, insulting and full of misplaced condescension, beginning with the very first paragraph:

Americans can save billions of dollars annually on credit card and other interest payments by raising their credit scores, but many consumers still don’t know enough about the complex numerical values that represent their credit risk.

Rugaber is certainly correct that Americans need to know how credit scores work. The ability to manage these “complex numerical values” is a vital and necessary skill for anyone with money in the bank, or a mortgage, or a car loan, or car insurance, or health insurance, or a job. Not knowing exactly how credit scores work will cost the average American hundreds of dollars a year in fees and interest, sometimes invisibly.

Pop Quiz: Following are two possible explanations for why most Americans are in the dark about the meaning and manipulation of credit scores. Which do you think is more important?

A. We Americans are lazy and ignorant people who can barely manage to feed ourselves unless tut-tutted and prodded by parental figures like Christopher S. Rugaber for our own good.

B. The calculation of credit scores is a protected trade secret, proprietary information closely held by the triumvirate of Transunion, Equifax and Experian, and therefore, legally, by definition, such information is unknown and unknowable by anyone not working for those unelected entities, including you, me and every personal finance reporter in the business including Christopher S. Rugaber.

Rugaber’s article presumes A as the only possible explanation for why most Americans are unfamiliar with how credit scores work. Explanation B — that this information is legally, officially and emphatically kept hidden from consumers — never enters his article or, apparently, his mind.

The article passes along some of the hints, guesses and inferences that we the public have been able to figure probably help to improve credit scores — don’t max out credit cards, “avoid opening multiple new accounts quickly, and pay off debt rather than moving it around,” don’t miss monthly payments, etc. But these are all just guesses. How exactly all those things affect our credit scores isn’t something we’re allowed to know.

Lenders and debt merchants are in the same boat as the rest of us. They don’t have access to the extra-constitutional triumvirate’s top-secret proprietary information either. But credit-card banks and mortgage brokers and insurance companies and auto lenders have more time, resources and incentive than consumers do for probing the mysteries of these all-important formulae. They’ve pieced together enough of the puzzle that they’ve gotten quite skilled at manipulating this statistical game to their advantage.

Rugaber notes, for example, that “credit card issuers … have recently cut limits on many cards as financial institutions seek to reduce their credit risks.” Limiting risk is one explanation for this step. An additional explanation is that this step alters borrowers’ “utilization rate,” and the cabalistic scholars of credit scoring at these institutions have determined that higher utilization rates make for lower credit scores, thus providing a quantitative fig-leaf for aggressive increases in fees and interest rates.

Here’s how the scam works. You’ve got a $10,000 limit on a credit card and you’re carrying $2,500 due to a recent dental procedure. The lender, in the name of reducing risk, abruptly reduces the limit on your card to $4,000, announcing this change on page seven of the nano-type in a booklet mailed with your next monthly bill. Now instead of a 25-percent utilization rate, you’ve got a 63-percent utilization rate (they round up, when convenient), lowering your credit score.

That lower credit score means you no longer “qualify” for your previous rate of 9.9 percent and will now be paying 19.1 percent. Oh, and there’s a one-time fee of $35 dollars, conveniently added to your existing balance, for exceeding 50 percent of your available limit.

Unfortunately for you, these changes in your balance and rate became effective at 9 a.m. on the 15th of the month. Your electronic payment, dutifully set for the previous minimum payment, is credited to your account at 1 p.m. on the 15th. That minimum payment was based on the earlier interest rate, so it’s no longer adequate to cover your newer, higher minimum payment. A $35 late fee is therefore added to your balance and this delinquency is reported to the triumvirate, contributing to the further reduction of your credit scores. Second verse, same as the first.

For a heartbreaking, in-depth look at the end result of this process, see Gretchen Morgenson’s article, “Given a Shovel, Americans Dig Deeper into Debt,” in Sunday’s New York Times. The headline writer there was drunk with the same condescension that ruins Rugaber’s AP article, but Morgenson’s piece itself provides a much more rounded and accurate picture.

Rugaber is certainly right that consumers need to be better informed about this. But his article seems to assume that it might be possible for consumers to compete with the debt merchants on a level playing field. As though the average person has the same kind of time, resources and expertise as those institutions do. As though the game wasn’t rigged. As though we must simply, passively accept the unchecked, unregulated and unrestrained influence of the unelected triumvirate to dominate our economy and our lives.

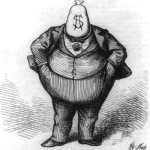

Americans don’t need yet another lecture from yet another personal finance reporter. Americans need torches and pitchforks.