Left Behind, pp. 343-344

We’re back at the Pan-Con Club at JFK. If this were a TV show, movie or play I’d admire the economy and resourcefulness the authors demonstrate here in reusing this set so many times. In a supposedly globe-trotting novel, though, this repetition seems less like efficient set design and more like a failure of imagination.

Thrillers like this are supposed to take the reader to exotic locations around the world, to present travel as adventure. Left Behind is more like business travel — an endless parade of interchangeable airplanes, airport lounges and hotels that all blur together so you can hardly tell what city you’re in or whether it even matters if you could.

Rayford Steele is beating himself up for not yet having convinced Chloe and Hattie to convert to whatever it is he now believes. His fretting here is a classic example of evangelical anxiety, the crippling dread that one is personally responsible for condemning others to eternal torment. Much of Rayford’s self-flagellation here is familiar to anyone who has witnessed — or felt — that particular variety of guilt.

He felt like a wimp. … What was the matter with him? Nothing was as it was before or would ever be again. If Bruce Barnes was right, the disappearance of God’s people was only the beginning of the most cataclysmic period in the history of the world. And here I am, Rayford thought, worried about offending people. I’m liable to “not offend” my own daughter right into hell.

This bit about “offensiveness” is boilerplate from many an evangelical sermon — the kind of sermon that exhorts others to proselytize without itself being a message of evangelism. Like most such sermons, Rayford’s mini-lecture here — intended for the reader as much as for himself — functions like a pep-rally. It’s intended to foster bravado, an exhortation to “screw your courage to the sticking-place.”

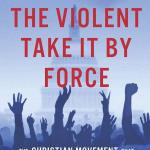

These pep-rally sermons pretend that any hesitation to proselytize — in the precise way, and with the precise message, that they prescribe — is a matter of cowardice and fearfulness. Specifically, they pretend that this hesitation must be the product of a fear of mockery and ridicule, of being called foolish.

But to the extent that fear plays a role at all in this hesitation, that’s not what their listeners are really afraid of. They’re not afraid of being called foolish, they are afraid that this accusation might be right. They’re not afraid that someone will say to them, “That’s nonsense. You don’t really believe that, do you?” They’re afraid that it really is nonsense, and that maybe they don’t really believe it after all.

No such sermon is complete without the obligatory recitation of St. Paul’s charge to “be not ashamed of the gospel of Christ.” Yet the “gospel” these sermons advocate spreading has little to do with anything Paul would have recognized as “the gospel of Christ.” That, I think, is the real cause of the reluctance most hearers have to proselytize in the way these pep-rally sermons advocate. Just look at the so-called gospel that Rayford is trying to persuade himself to preach. It portrays God as an arbitrary and pettily vindictive djinn constrained to do his bidding by the recitation of magic words. His reluctance to spread this “gospel” is not a matter of cowardice, but of conscience. He’s not embarrassed at the prospect of seeming “offensive” or “politically incorrect” (the preferred self-congratulatory term for the enthusiastically offensive) — he’s legitimately embarrassed.

Rayford also felt bad about his approach to Hattie. He had dealt with his own wrong in having pursued her, and he regretted having led her on. …

Rayford thinks he has “dealt with” his mistreatment of Hattie because he has asked God to forgive him for it. Yet he hasn’t apologized to Hattie or asked for her forgiveness, nor does he seem to see any need to do so. This appears, at first glance, to be an example of an exclusively vertical faith lacking any horizontal aspect — meaning a faith that is concerned only with one’s relationship to God and not with one’s relationship to other people (as if such a thing were possible). But really his faith has little to do with God either, except insofar as God serves as a means to his ends. His wrongs are “his own wrongs.” It’s all about him.

This is reflected, too, in the thrill he gets from the idea that he is living in “the most cataclysmic period in the history of the world.” That thrill — which plays a big role in the allure of premillennial dispensationalist apocalypticism — comes from the idea that this makes him special, that it makes his life more meaningful than it might otherwise seem. Rayford’s language echoes other expressions of this desperate quest for vicarious meaning that comes from living in “interesting times.” That attitude only makes sense from an extremely self-centered perspective: Sure, the apocalypse means widespread suffering and death, but it makes my life more significant, so on balance that’s a plus.

Rayford muses a bit more about this cataclysmically important new age:

Whoever came forward with proclamations of peace and unity had to be suspect. There would be no peace. There would be no unity. This was the beginning of the end, and all would be chaos from now on.

The chaos would make peacemakers and smooth talkers only more attractive. And to people who didn’t want to admit that God had been behind the disappearances, any other explanation would salve their consciences.

That’s a stark and succinct statement of two of the authors’ core beliefs:

1. “Peace and unity [have] to be suspect.” Anyone not advocating chaos is not to be trusted.

2. The truth of their particular beliefs about God can either be “admitted” or actively denied. Anyone who claims to believe anything else is deliberately embracing what they know to be nonsense as a way of hiding from the irrefutable truth.

The authors’ also suggest here that periods of chaos “make peacemakers more attractive.” Rather than chaos and insecurity opening the door to strongman demagogues offering security in exchange for unlimited power, LaHaye and Jenkins think insecurity makes people more susceptible to the appeal of complete and unilateral disarmament.

In any case, Rayford is determined to play his new and cataclysmically important role in this new and cataclysmically important era:

There was no more time for polite conversation, for gentle persuasion. Rayford had to direct people to the Bible, to the prophetic portions. He felt so limited in his understanding. He had always been an erudite reader, but this stuff from Revelation and Daniel and Ezekiel was new and strange to him. Frighteningly, it made sense. He had begun taking Irene’s Bible with him everywhere he went, reading it whenever possible. While the first officer read magazines during his downtime, Rayford would pull out the Bible.

“What in the world?” he was asked more than once.

OK, no. That didn’t happen. Definitely not “more than once,” and probably not even once. First off, we’ve seen what Rayford does with his “downtime” at home: he watches TV and he talks on the phone. He read the Bible on the night he was converted, but since then it’s been all CNN and Nightline. Second, Rayford has had only three flights since his conversion. He flew to Atlanta and back with his daughter along, spending all of his downtime with her. And Chloe again has accompanied him on this, his third trip, during which he has again spent every moment outside of the cockpit talking with her. I suppose that he may have had a few moments between taking off from O’Hare and landing at JFK during which he might have opened his Bible, but at that point the first officer would have been flying the plane himself, and so he probably wouldn’t have had the chance to glance over to Rayford and implausibly ask, “Whatcha readin’? Looks like the prophetic portions of the Bible. …”

My guess is that his first officer simply overheard some of Rayford’s wincingly awkward conversations with Chloe — conversations in which he has explored every detail of his long, kinkily sexless flirtation with Hattie. Suddenly realizing how repressed Steele really is, and how messed up he’s got to be to be talking about that stuff with his own daughter, his co-pilot involuntarily gasped, “What in the world?” Hearing this, Rayford assumed it had to be an expression of awed admiration for his courageous witness on behalf of the Gospel of the Apocalypse.

Overall, though, Rayford is disappointed by the contrast between the boldness with which he opened his Bible that one time on the plane and his reluctance to be as boldly “offensive” closer to home:

“What in the world?” he was asked more than once.

Unashamed, he said he was finding answers and direction he had never seen before. But with his own daughter and his friend? He had been too polite.

So wait … Hattie is his “friend” now? I’m not sure which is creepier: that he would refer to her by that term, or that he really believes that he has ever been “too polite” when it came to Hattie.