If you'd opened our paper Wednesday to pages 2 and 3 of the local section, you'd have read the following headlines: "10 charged in alleged child porn network," "Man charged with rape of teen," and "Father of two pleads guilty in child porn case." All on the same day. Yeesh.

Anyone who is proven guilty of the things these men are accused of needs to be taken off the streets. Incarceration is needed in such cases for all three of the classic reasons: public safety, punishment and deterrence. (I don't know how effective the last really is, though, since these crimes don't tend to be the result of rational calculation, but such as it is I think the pedagogical effect here still matters.)

But here's the problem: If any of these dozen suspects gets convicted, do you know what will happen to them in prison?

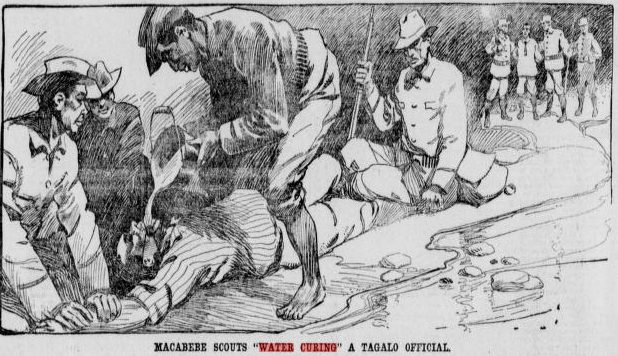

That's a yes or no question. and the answer is yes. You do know — we all know. They will very likely be beaten and raped, repeatedly. They will, in essence, by be sentenced to torture, to cruel and unusual punishment. This violates the Eighth Amendment, and it violates basic decency. It is both illegal and inhuman. Like all torture, it is intolerable and counterproductive.

The fact that this torture will be administered at the hands of their fellow prisoners and not by officials of the state hardly matters, because the state is — we are — placing them into a situation in which we all seem to know that this is what will happen. The state's hands are clean only in the meaningless technical sense that America's hands are "clean" in cases of extraordinary rendition — when we ship terror suspects off to Syria or Saudi Arabia, outsourcing torture.

I have no experience in, and know very little about, the administration of prisons. It baffles me that they should be such violent, gang-controlled, drug-infested places. I have a hard time grasping how it is that such institutions — places where every meal and movement is monitored and controlled — are so lawless. But I'm assured by those who know more than I do that this is the case and that there seems to be little that even the most able administrators can do about it.

What we need, then, are separate prisons. We need different institutions to house different types of criminals. If the sexual predators who prey on children cannot be incarcerated in our current, one-size-fits-all prisons without being subjected to beatings and rape — to torture — then it seems we should at least try creating separate prisons for these men, places where they can be incarcerated apart from the prisoners who will, almost certainly, subject them to such crimes.

(Glibly accepting the current state of affairs — "Do you know what happens to people like that in prison?" — also undermines the law. It suggests that beatings and rape are, in some cases, acceptable or tolerable. The corrosive pedagogical effect of that trumps any useful deterrent effect of incarcerating "people like that.")

Creating such separate prisons is politically unlikely. Any such effort would be attacked as an act of soft-hearted sympathy for those who prey on children. Such attacks may be politically effective, but they are either dishonest or misinformed. This has nothing to do with sympathy for criminals, it has to do with us, with who we are.

As is often the case, Hilzoy states this more clearly than I am able to. The subject of Hilzoy's post is the "Black Sites" — the secret overseas CIA prisons in which terror suspects are subjected to various, blatantly illegal, forms of torture. Simply substitute "pedophile" or "child pornographer" for "terrorist" in Hilzoy's post and every word of this applies to my argument above:

Whenever I write a post like this, someone pops up in comments to ask why I am so concerned about the fate of terrorists. In many cases, I don't have to engage with this question: many of the people we have held and tortured are innocent. In the case of the program described in this report, however, I would assume that many, though not all, were terrorists. So it's worth saying explicitly that this is not, for me, just about feeling badly for the people we have detained and abused. Sometimes I feel very badly for them, especially in the case of those who are, as best I can tell, completely innocent; but feeling badly for them is not essential. Because there's another motivation at work, namely: concern for my country, and the desire that it be the best country it can be.

There are some things we, as individuals, should not do to other people. Often, we will also sympathize with those people, and that sympathy might prevent us from, say, torturing or raping them. Sometimes we feel no sympathy, however — the other person might be a person only a saint could sympathize with, like Jeffrey Dahmer. If our only reason for not torturing or raping people was sympathy, then when faced with such a person, we might have no reason not to do whatever we liked to him or her. But sympathy is not our only reason for not torturing and raping people. There's also self-respect: the thought that whatever someone else might choose to be like, and even if that person has chosen to be Jeffrey Dahmer, there are certain things that I will not choose to do, because I do not want to be the sort of person who does them.

If someone saw me not torturing Jeffrey Dahmer and said: Gosh, there's hilzoy, all undone by the thought that such a horrible person might suffer even a teensy bit of pain, I would think: sorry, but you do not understand why I am doing this at all. And if someone thinks that the reason I do not want my country to abduct children, to disappear people without charges and without trial, to waterboard them, or to keep them in isolation for months on end, is nothing but concern for them, they are making a similar mistake. I feel terrible about what we have done to a lot of people — the Uighurs, for instance. I do not have a lot of sympathy for Osama bin Laden. But that fact has precisely nothing to do with my thinking that there are certain things I simply do not want my country to do, even to him.