Since before the American-led invasion of Iraq four years ago, I have written more than once about possible bad outcomes from this adventure. "Gaza on the Tigris" has come to seem the most apt of these possibilities, but it was not the worst-case scenario.

The worst-case scenario is something more like Rwanda in 1994, about which more in a bit, but first let me clarify something about the meaning of "worst-case scenario."

By "worst-case scenario" I mean the outcome I dreaded, not what I necessarily expected, and certainly not what I wished for.

That would seem self-evident to anyone who understands the word "worst," but we live in strange times, times in which a disturbing number of people claim to believe that giving any thought to worst-case scenarios and potential bad outcomes is equivalent to desiring such bad outcomes. They claim that they can see no distinction between planning against the worst and hoping for it. Thus those of us who opposed this war and were pessimistic about its prospects are accused of wanting America to lose, of giving "aid and comfort to the enemy" and of all manner of similar sickness.

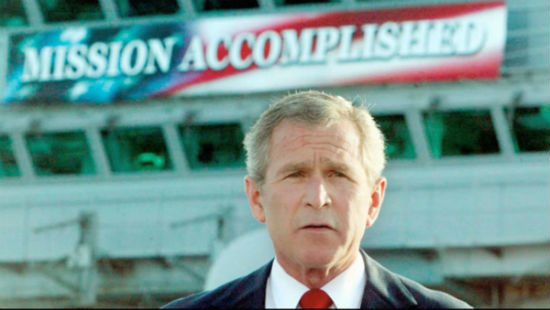

The consequence of this way of thinking is that worst-case scenarios, and even less-than-optimal-case scenarios, are never considered. To imagine Plan B, the logic goes, is to hope for the failure of Plan A, and hoping for such failure is tantamount to treason (giving "aid and comfort," etc.). Thus, to avoid such treason, the invasion of Iraq was planned for and conducted with Plan A and only Plan A in place. That plan involved a military "cakewalk" with American forces being "greeted as liberators," followed shortly thereafter by the flowering of a pro-America, pro-Israel democracy, funded by privatized/westernized oil revenues that would limit American expenditures for reconstruction and nation-building to $1.7 billion.

This sounds like mocking exaggeration, but it is not. That was precisely the plan. The phrases "cakewalk" and "greeted as liberators" were actually spoken, and $1.7 billion was the precise figure cited by the Bush administration. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld said that America's military involvement, "Could last, you know, six days, six weeks. I doubt six months." That was Plan A and there was no Plan B. Plan B could not be allowed, because even to think of it was to hope against, and somehow even to bring about, the failure of Plan A.

Members of the Bush administration — from the president himself, to Vice President Cheney and on down through Rumsfeld, Rice and White House spokesmen Fleischer, McClellan and Snow — have repeatedly accused critics of the war in Iraq of undermining that effort, aiding the enemy, wanting America to lose and "the terrorists" to win, etc. I've mostly thought of this as a disingenuous and despicable bit of political theater — a desperate attempt to use the "stabbed in the back" myth of Vietnam as political insulation against being held accountable for what Sen. Chuck Hagel, R-Neb., called "the worst foreign policy disaster in American history."

But it's also possible that these accusations are sincere — that they really believe this. It is possible that they really cannot see any distinction between planning against contingencies and hoping for failure, between carrying an umbrella and hoping for rain, between carrying an umbrella and causing rain.

For evidence that their inability to make such a distinction is sincere, see again their planning and conduct of the war in Iraq. Their refusal to consider or to plan against any sub-optimal contingency was steadfast. Four-star generals got fired for mentioning less-than-perfect possibilities. Gen. Garner was prohibited from hiring anyone who had ever been involved with contingency planning for a post-Saddam Iraq.

I still tend to think that this disastrous refusal to consider anything other than a pie-in-the-sky Plan A was a deliberate, political decision. I think the Bush administration was so desperate to win public support for its desired invasion that no discussion of any potential less-than-perfect, less-than-easy, possibilities was allowed — even internally. If the public got wind of any consideration of a possible downside, the administration might not get to have its war. This political motive trumped military prudence and military necessity. That seems to me to be the likeliest explanation for their criminally negligent refusal to allow any consideration of Plan B.

But the Bush administration's behavior, its determination never to plan against worst- or less-than-best-case scenarios, is also consistent with the sincere belief that any such planning is a kind of "defeatist" treason, the sincere inability to distinguish between planning against contingencies and wishing for/causing them. This is such an elementary distinction that it seems impossible that any group of adults capable of tying their own shoes could really fail to understand it. Yet we have another piece of evidence that this may be the case: Bush, Cheney, Rice and Snow have repeatedly said so. They have all, time and again, stated that critics of the war are aiding "the enemy." They have all, time and again, claimed not to understand any distinction between planning against contingencies and deliberately causing failure.

This last piece of evidence is not persuasive. Their stated claims require us to accept that they are all incapable of the kinds of elementary distinctions that make one mentally competent. People who are truly incapable of making such distinctions do not have jobs like vice president or secretary of state or White House spokesman. They have jobs assembling boxes under the supervision of caseworkers. It seems more charitable to me to presume that their claims are disingenuous rather than to presume that they are mentally incompetent.

In either case, the outcome is what it is. The refusal to plan for contingencies left the Bush administration unprepared to face such contingencies as they arose. That reckless lack of preparation — whether due to mental incompetence or to horrifically cynical political calculation — has been a death sentence for thousands of American troops and tens of thousands of Iraqi civilians.

The administration had it backwards. Planning against worst-case scenarios does not cause them to happen; failing to plan against them can.