"Tell me about it if it's something human."

— Robert Frost, "Home Burial"

So the more difficult empathy seems, the more necessary it probably is. And probably vice versa. This is inconvenient, but there you go.

For each of us, there are certain people, and categories of people, whom we find it difficult to consider with empathy. By that, I don't just mean people with whom we disagree, but people we just plain don't get — people we just don't understand.

It's quite possible to disagree with someone without finding them strange and alien. I disagree with libertarians, but I get where they're coming from. Their ideology and the values that inform it are rather straightforward. So, while I disagree with some of that ideology, libertarians are not, to me, inexplicably other and I don't find it that difficult to consider their perspective with empathy or to understand what they want and what they value.

But, to take an extreme example, I have no idea what to make of someone like the Rev. Fred Phelps. What he wants, and why, and why he wants it so very badly, is a mystery to me. I find it nearly impossible to try to view the world from his perspective. And I find it unpleasant to try. "Tell me about it if it's something human." In Phelps' case, I'm not sure it is something human.

I mentioned earlier that acting is, among other things, an exercise in empathy. The Rev. Fred Phelps is, intriguingly, a character in the play The Laramie Project. All the "characters" in that play are real people, and their lines are all words they really said. It's a remarkable play, and I'd love to be in it if I get the chance. But I wonder what I'd do if I had to play the part of the Rev. Phelps. It would be easy to play him as a caricature — he seems to be a caricature — and I wonder if I could get beyond that and portray him as an actual human being. Doing so would probably involve some kind of radical choice — playing him as a repressed homosexual, or as himself the victim of some horrific abuse, or as an Iago-like cipher of motiveless evil. But such a choice wouldn't arise naturally from the character himself because I just can't figure this guy out at all.

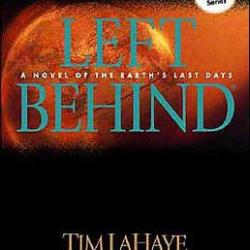

The apostle of hatred is, as I said, an extreme example. But there are many other people that I just don't understand, people I find it difficult to view with empathy. One such category of people would be those who — like our friends LaHaye and Jenkins — do not themselves seem to regard empathy for others as a valuable or necessary commodity.

Then there's that other inconvenient thing about the difficulty and necessity of empathy: there are also probably lots of people that I don't understand that I don't know I don't understand. (If you've been reading this blog for a while, you may actually have a better idea of who those people are than I do.) Tricky thing about empathy — even at its best, it only allows us to know others as well as we can know ourselves.