I agree with the idea mentioned below that public servants ought to be paid well enough to insulate them from the temptation to corruption that financial hardship can bring. Call it the Eddie Cicotte theory — after the great White Sox pitcher who helped to throw the 1919 World Series.

But there's a problem with the Eddie Cicotte theory. It only applies to one type of greed, and the least troubling sort. The greed that arises due to financial hardship is need-based. If we ensure that public servants' financial needs are met, we can eliminate the problems caused by this type of greed.

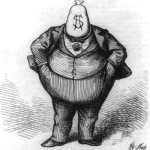

More pernicious, however, is the insatiable greed that has nothing to do with actual financial needs. This kind of greed cannot be avoided by ensuring that officials are paid enough because, by definition, those infected with this kind of greed can never have "enough." This is greed in its purest form, undiluted by the mitigating circumstances of need, despair and self defense that limit the former kind. It is acquisitive and it will not stop until it owns and controls everything.

We seem, perversely, more attuned to worrying about limited, need-based greed than to preventing greed in its unlimited form. If a lawmaker with personal financial struggles supports a bill that would, among other things, provide a $2,000 tax break for people like himself, his vote will be scrutinized as though he were caught taking a bribe. Yet when millionaire lawmakers pass tax breaks for all millionaires, no one bats an eye. President Bush personally reaped more than $40,000 a year from his 2001 tax cut, yet this windfall wasn't considered worthy of scrutiny because, after all, what's a mere $40,000 a year to a wealthy guy like George W. Bush?

Thus wealthy lawmakers have a blank check to keep writing themselves blank checks. And they do.

This is corruption. Blatant corruption far worse, and with far higher stakes, than anything the infamous Black Sox ever imagined.

For a current example, consider this fact sheet prepared by Rep. Henry Waxman, D-Calif., of the House Committee on Government Reform. It examines the personal benefits for the president and his cabinet if the estate tax is permanently repealed. Waxman notes that "it is impossible to know exactly how a person will structure his or her estate" or to know "exactly what assets a person will have at their death," so he provides a range of estimates. Here's a taste of what Waxman found:

George W. Bush: $787,193 – $6.2 million

Dick Cheney: $12.6 million – $60.7 million

Donald Rumsfeld: $31.8 million – $101.3 million

John Snow: $22.9 million – $69.8 million.

Let's just take the low end estimates there.

President Bush supports the abolition of the estate tax. This policy would cost the Treasury trillions of dollars over the coming years. It will cost the nonprofit sector billions of dollars a year, causing charities to shrink and cut back. President Bush offers no credible argument in support of this policy. If it becomes law, he will personally receive more than $787,000.

That's one hell of a bribe. $787,000 dollars. Yet we're supposed to believe that the prospect of reaping this huge sum of money has absolutely zero influence on George W. Bush's enthusiasm for this otherwise inexplicable piece of legislation.

Dick Cheney is also incapable of explaining why the estate tax should be repealed. But he's for it. Such a repeal would reap at least $12.6 million for him personally, but that, we're supposed to believe, has nothing to do with his position.

$12 million is enough of a bribe to tempt even the purest of saints. And Dick Cheney ain't no saint. Yet we're supposed to blithely accept that this $12 million windfall has utterly no effect on his decision-making.

I rounded down there, did you catch that? I rounded $12.6 million down to $12 million. That decimal point I knocked off there represents $600,000, or roughly what the average American family will earn over the next 10 years. If your bank account were to suddenly swell by this amount — $600,000 — you would have a very difficult time convincing a judge that it was meaningless, a trivial sum that had no influence on your actions and that you had done nothing questionable to acquire. But Dick Cheney will never have to stand before a judge to account for that $0.6 million, or for the $12 million before the decimal point.

George W. Bush and Dick Cheney aren't like Eddie Cicotte. Money does not, to them, represent an escape from financial hardship. It is not something they need, but it is something they love. Men like that won't sell out for a mere $10,000. But for $787,000? For $12.6 million?