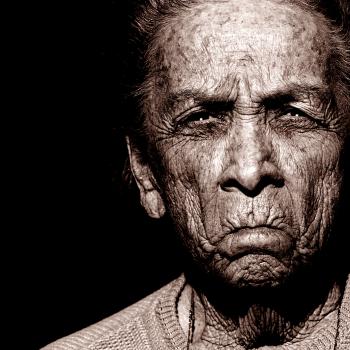

There’s an old joke about politics: conservatives hate people in general but love them in particular, and liberals are exactly the opposite. This cheeky barb might bring to mind, say, your socialist roommate in college whose passion for total equality somehow never seemed to extend to household cleaning, or your Fox News-watching aunt whose principled disdain for immigrants is bafflingly hard to square with the warmth she showers on family. Fascinatingly, a new paper from a team of moral psychologists offers evidence that this stereotype – conservatives care more about close social circles, while liberals care for wider circles at the expense of the smaller – isn’t just a cranky witticism.

Led by Northwestern University psychologist Adam Waytz, the team, which included New York University’s Jonathan Haidt, first analyzed survey data gathered at their well-known website, YourMorals.org. The popularity of this site meant that they had lots of data to chew on – anywhere from two to fourteen thousand participants per study – for exploring relationships between ideology and social values. Let’s get right into what they found.

Moral Circles and Dots

The first study used a measure that examined respondents’ feelings toward romantic partners, family, friends, and humanity at large. For example, one item asked subjects whether “there are times in my life when I’ve felt strong feelings of love for all people, not just the specific people I’m close to.” As expected, conservatives felt significantly less love toward people at large, indicating that their “moral circles” – a concept popularized by philosopher Peter Singer to refer to the breadth of one’s perceived in-group – were smaller and more constrained than those of liberals. Conservatives also felt more love toward family and less toward friends than liberals, although these effects were small. Matching up with stereotypes, conservatives seemed to care more about the people closest to them, and liberals about the wider circles of humanity.

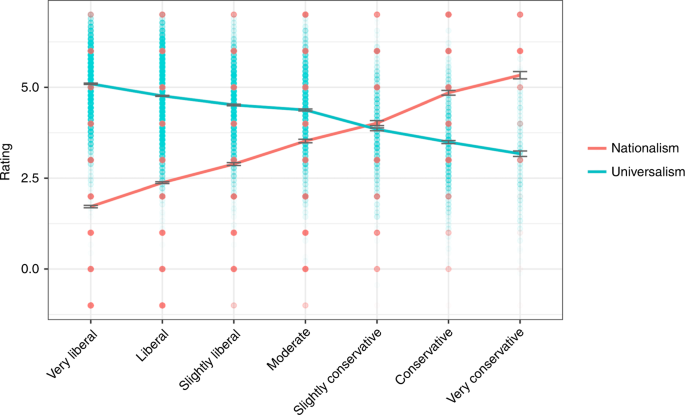

A second study used a different measure to confirm that conservatives were much less universalistic and more nationalistic than liberals, while a third used a measure called the “Identification with All Humanity Scale” to show that conservatives identified more strongly with their local communities and with their own nation-states than liberals, who identified more strongly with “the world.” (See the figure below.)

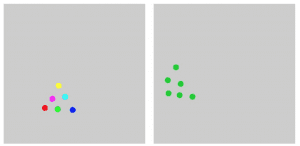

The next set of studies took things in a slightly different direction. Reasoning that the differences between conservative and liberal sensibilities might reflect a deeper distinction in cognitive processing styles, Waytz and his colleagues analyzed data from a visual task in which participants indicated which shapes they liked better – tight geometric structures or loose, less coherent ones (see the next image below). As predicted, conservatives preferred the tighter images. The authors concluded that conservative values may stem from deeper, more basic cognitive preferences for order, predictability, and clear boundaries.

(Contrary to predictions, liberals did not show a significant preference for multicolored – internally “diverse” – images, which would have been a neat and totally expected little finding. Oh well.)

A subset of the participants who completed the shape-preferences studies had also completed the surveys on social values and ideology. Using these combined data, the authors found that preference for ordered shapes mediated – helped explain – conservative ideology’s effect on the size of participants’ moral circles. That is, conservatives’ smaller, tighter moral circles seemed to emerge out of their more fundamental preference for order and clarity.

Of Parents and Paramecia?

The final set of studies, conducted on a different online platform, asked participants to imagine that they had “moral units” that they could hypothetically distribute to a range of recipients. “Moral units” is a deeply unintuitive concept,* but you can think of the moral units like time and energy. Each day, we only have so many free hours and resources to devote to caring for different people. Do you prioritize your wife or husband, devoting more of your limited time and energy to him or her than anyone else? Or your children? Your friends, coworkers, students, distant relatives?

Hypothesizing that liberals’ capacious moral circles might even extend to the nonhuman – and potentially even nonliving – worlds, Waytz and his colleagues showed participants a set of concentric rings that represented potential recipients of care and concern. Participants then chose where they would invest their artificially limited store of 100 moral units. The concentric rings ran from the very innermost circle – “immediate family” – to the very outmost, “all things in existence.” Along the way were such categories as “all people in your country,” “all animals on earth including paramecia and amoebae,” and “all natural things in the universe including inert entities such as rocks.”

You read that right – paramecia and rocks.

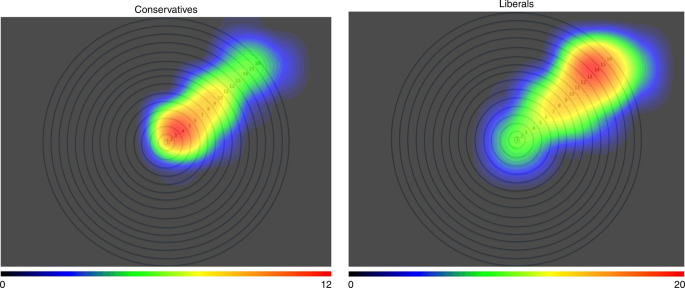

You can see the striking differences between conservative and liberal ideologies in the heatmap image at right (Figure 5 in Waytz’s paper), which shows the highest average allocations in red and the lowest in light green. The big red splotch centered near circles  3 and 4 on the left shows that conservatives tended to devote most of their care to subjects in the innermost four rings, from extended family to friends and acquaintances. By contrast, the almost completely inverted heatmap on the right shows that liberals invested the bulk of their hypothetical care near ring 14: “all living things in the universe including plants and trees,” with minimal allocations to close family. (Note that the center of this red spot was two rings further out than the paramecia, which languished in a mere orange patch in ring 12.) A second study with unlimited moral units replicated the same basic pattern, showing that the pattern in the heatmap images wasn’t simply due to artificially restricting the possible amount of care and consideration subjects hypothetically had at their disposal. Waytz et al. concluded that:

3 and 4 on the left shows that conservatives tended to devote most of their care to subjects in the innermost four rings, from extended family to friends and acquaintances. By contrast, the almost completely inverted heatmap on the right shows that liberals invested the bulk of their hypothetical care near ring 14: “all living things in the universe including plants and trees,” with minimal allocations to close family. (Note that the center of this red spot was two rings further out than the paramecia, which languished in a mere orange patch in ring 12.) A second study with unlimited moral units replicated the same basic pattern, showing that the pattern in the heatmap images wasn’t simply due to artificially restricting the possible amount of care and consideration subjects hypothetically had at their disposal. Waytz et al. concluded that:

these findings demonstrate that liberals and conservatives differ not in the total amount of moral regard per se but rather they differ in their patterns of how they distribute their moral regard…This difference manifested in conservatives exhibiting greater concern and preference for family relative to friends, the nation relative to the world, tight relative to loose perceptual structures devoid of social content, and humans relative to nonhumans.

You couldn’t get a more powerful illustration of the basic conservative and liberal orientations toward in-groups, respectively. Conservative thinkers throughout history have indignantly accused liberals and progressives of relying too much on abstractions and grand theories, while real relationships and communities go neglected in their own backyard. Liberal thinkers have retorted that conservatives are parochial snobs, caring only for their limited in-group instead of the greater good. This study – and especially the telling heatmap images – concretely demonstrates that, whatever their other flaws, liberal and conservative thinkers aren’t wrong about each other here: conservatives really are parochial, and liberals really do (claim to) care more about the welfare of outsiders than of their neighbors.

Reality Check

Of course, real liberals – with maybe a few exceptions – actually do care more about their grannies and neighbors than about single-celled lifeforms in an ocean steam vent somewhere. While progressive ideologies might idealize broad moral circles, the fact is that we’re embodied creatures who depend on particular families and groups of friends for our wellbeing – for our very lives, even. These limiting facts of our human biology and sociality mean that, from our limited perspective, certain people are just always going to seem more important than others.

Liberals might respond that, yes, this may be how it has to be, but it’s a tragedy. Ideally, we should dream persistently of a world where everyone loves everyone else equally, even if we have to concede the practical, if ugly, necessity of prioritizing family and friends – at least in this unhappy dispensation. Liberalism (in Waytz et al.’s sense) sees moral parochialism as, at best, a necessary evil.

By contrast, paradigmatic conservatives see it as a positive good. What would the world be like if everyone cared more about the strangers living over the next hill than their own parents and next-door neighbors? It would be a lonely, arid, and unhappy place, with none of the close friendships and shared loyalties that make life worth living. More to the point, it would be completely free of…humans. We can’t live on our own – as an increasing body of research confirms, we hairless, weak-muscled, sharp-teeth-and-claw-lacking human animals are completely, helplessly dependent on cultural knowledge, instruction, and mutual aid for our very survival. You take the smartest, strongest Dwayne Johnson lookalike and toss him alone into a strange forest halfway across the world, with no knowledge whatsoever of the local flora or fauna, and give him a box of energy bars, and you know how long he’ll live? Well, how many energy bars are in that box?

All across the world, nobody possesses all the knowledge they need to survive alone. You learn how to hunt the particular animals that live in your particular corner of the world from your elders, who know the animals’ ways, know how to trap them, know which ones are poisonous. You learn how to farm by following your farmer parents around the homestead, absorbing their tacit knowledge: this kind of soil is good for barley, that one is better for garden vegetables. Along the way, you come to owe these people something: they’ve taught you how to survive, how to make it in the world.

As such, conservatives see liberal moral universalism not as a noble cri de coeur condemning close-minded nepotism, but as a canny means of squirming out of the obligation to be available to those concrete others on whom they, personally, depend. In other words, it seems like a bit of a racket. Liberals who hold universalistic ideals depend on family and friends just as much as everyone else does, but by pretending to care more about abstract groups of strangers than about their own social circles, they awaken conservatives’ fear that they’ll take from concrete others – friends, family, and nation – without giving back.

Of course, to liberals this sounds absurd – who’s willing to pay more taxes to support society? Who wants to fund education? But this leads us to a whole different battlefield, and I think we’ve already covered enough ground for one day. After all – as conservatives would admit – you only have so much of yourself to spread around.

–––––––

* And one that poignantly illustrates the unfortunate way in which the social sciences are almost forced, by their very nature, to be rhetorically barbarous, in the exact way that poetry isn’t.

–––––––

I’m at the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion conference in St. Louis this weekend. If you’re around, come say hi! Oh, and all figures from the Nature Communications paper by Waytz et al. are open access creative commons.