Connor Wood

In my last article, I dissected the study that went around the Internet claiming that children who have been exposed to religion (like swine flu) can’t tell the difference between reality and fiction. Those findings were less than convincing, as I and others pointed out – because kids who had been to Christian Sunday school were virtually guaranteed to recognize the “fictional” stories as versions of Bible narratives. So the research actually only showed that religious kids believe religious things – which, duh. Take a step back, though: the hand-wringing commentariat worried that the faithful might be dangers to society, due to their supposed disconnect from reality. But does believing impossible things, in principle, constitute such a terrible threat? Do we even want a world where people can accept only the facts?

In our era of scientific triumph, this seems like a positively sacrilegious question. Scientifically proven facts are the difference, we’re told, between cowering in caves and living comfortably in climate-controlled homes, between endless religious wars and landing on the moon. Of course we want a world where people only believe the facts, right?

Yes, of course, but for one little detail: facts change.

Sounds absurd, right? Facts are supposed to be facts. Incontrovertible truths. The opposite of opinion. Not hearsay. For example, it’s a fact that the atomic weight of elements is a function of the number of protons and neutrons in their nuclei. It’s a fact that airplanes fly due to Newton’s laws of motion and the conservation of energy and momentum.

But not that long ago, the educated consensus was that flight was an impossibility. And we weren’t even sure there were atoms – Einstein only proved the atomic theory of matter using Brownian motion 110ish years ago. What’s more, in Einstein’s early years it was a fact that, if atoms did exist, they were indivisible. (That’s what the Greek root of the word “atom” means.) So when, between 1908 and 1913, the physicist Ernest Rutherford showed that atoms were actually comprised of dense, charged nuclei surrounded by a less-dense shell,* he changed the facts. And when the Wright brothers flew their first flight at Kitty Hawk in 1903, they changed the facts, too.

Don’t misread me. It wasn’t reality that changed. It was our understanding of reality that did. But facts are never anything but our current, best understanding of reality. When our understanding of the world shifts, we need to be ready to reevaluate what’s true or possible. If we’re too rigid to reconsider our understanding of the facts, we end up with unfortunate phenomena like, say, conservative climate denialism.

Imagination, in other words, is necessary for the progress of knowledge. You have to imagine a new perspective before you can evaluate it or design a crucial experiment. This is why a researcher with a slightly kooky view of reality is a great asset to any scientific team. And why an engineering student whose view of fact and fiction is slightly blurry might be the first one to solve our longstanding energy conundrums. Openness to the impossible – and I mean the really impossible, the opinions that makes your colleagues look at you funny – is a prerequisite for truly radical advancement. Every great step in the march of genius is taken by some damn fool who either refuses to concede to, or is simply ignorant of, what’s impossible.

What’s interesting is that the authors of the religion-and-reality study, led by Boston University researcher Kathleen Corriveau, suggest that religious stories might actually enhance this imaginative faculty. They wonder whether exposure to Biblical miracle stories might foster “greater inclination to imagine circumstances in which an intuitively unlikely event could happen,” and they suggest that

It is possible that religious instruction helps children to engage in such imaginative reflection with respect to impossible events… Thus, it prompts them to think about ways an otherwise impossible event could happen even if their immediate intuition is that it could not.

Imagination is not a luxury good; it’s a necessity. People need imagination to creatively solve the problems of life, and civilization needs imagination to thrive and grow. If Corriveau is onto something above, then the apparent fictions that religions foist on their faithful are a sort of lifelong practice at entertaining impossibility. In fact, she is right – religions are humanity’s oldest tools for exercising the muscles of the imagination. Sure, this can lead to dangerous outcomes. But a world where no one could imagine the impossible – and again, I mean the really impossible, the kind of stuff that makes your friends shake their heads when they talk about you – would be even more dangerous. By far.†

Nevertheless, there is a growing movement to simply banish imagination from the human world. One writer, Rob Brezsny, calls this movement the global “genocide of the imagination,” and I think he’s spot-on. Ostensibly, this war is being waged because, after 9/11, thinkers like neuroscientist Sam Harris decided that religion and fantastical thinking leads to wars and myopic, illiberal opinions, and must be stopped. But don’t forget (as the Gmork sneered in The Neverending Story) that people with no imaginations are easy to control. A world of people unable to fantasize alternatives – incapable of seriously entertaining apparent impossibilities – would be one with no rebellions, no revolutionary scientific breakthroughs, no history-forging leaders. It would be a world that never changed.

Boy, that sounds like a blast.

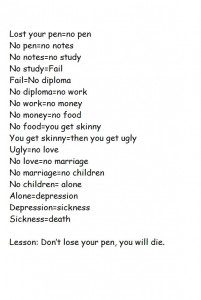

Even at the everyday level, the symptoms of a strangled imagination are grave. Our brains are machines for producing cause-and-effect stories – we input our experiences, and our craniums spit out causal schematics whose purpose is to give us maps of reality. To us, these cause-and-effect stories always seem plausible and logical. In fact, they’re so plausible that if we don’t learn to question them they can easily become all-convincing – see the much-shared image to the right for an example. Lose your pen, and that darn iron chain of cause and effect leads to your inevitable death.

Ridiculous, isn’t it? Except anyone who’s ever experienced serious depression or mental illness knows that this is exactly how our minds work. Our brains trick us into believing absurd, dangerous stories all the time. How about this one: “You’re an idiot. You’ve never been able to do anything right. That’s why people don’t like you. And since people don’t like you, you’ll never have an enjoyable life.”

Notice that every link in the chain of this nasty little story seems to flow logically from the one before it. On its own terms, this story is completely compelling to the person whose brain is telling it. And so the more a person hears a story like this from her own brain, the more that story becomes “fact” – an incontrovertible truth, bound by the laws of cause and effect.

And so, paradoxically, the solution to breaking free from our brains’ death grips is not to be cold-bloodedly loyal to the facts, but to be imaginative enough to question whether the facts are true. It takes a sudden burst of fantasy to break through the stone walls of our minds’ dreary stories. It requires a robust exercise of the imagination to suddenly realize that what seems impossible is, in fact, possible – that we could, for example, do some things right and find friends who care for us. A lot of mental torture is caused not by unrestrained fantasy, but by unexamined and sedentary fact. Imagination is what dissolves these facts – shows us which of them are useful and which of them are simply trying to kill us.

So what happens when we extinguish the imagination – when we teach all children to only accept the plain facts, and to impatiently dismiss all fictions? Well, the facts become tyrants, and what’s accepted as impossible stays that way. Fundamental physics never goes anywhere. There was no Big Bang. And we’ve never put a single bootprint on the moon. Until our understanding changed, it was simply fact that all physical events were fully determined, that the universe was eternal and changeless, that flight and manned space travel were absurd. Anyone contesting these thoughts was thought to be woozy, possibly not the sharpest knife in the drawer. Albert Einstein himself – arguably the greatest physics genius of all time – was especially severe in his criticisms of quantum physics and the idea of the Big Bang. Why? Because the cause-and-effect stories he accepted about the universe were so rich, so well-informed, so complete, that they couldn’t let anything else in – not even new evidence.

If you think that historical scientific mistakes like this were just unfortunate early bloopers in our inevitable climb toward knowledge, but that now we’ve achieved enlightenment, that now everything we lucky 21st-century moderns believe is – finally – the real truth, then I have some fast-sinking real estate in South Florida I’d like to sell you. It’s not just likely that we’re wrong about some of the things we currently hold to be fact. It’s an absolute certainty. We don’t know which ones. But if we decide to start calling it mental illness or subpar mental performance when anyone entertains a different version of reality than the currently accepted one, we’ll run out of genius pretty quickly. (This might already be happening in the Ivy League, where competitive, under-pressure students are taking fewer creative risks and rocking the boat less and less.)

Common sense says that religious stories are absurd. This is true – they are absurd. But they are not valuable in spite of their absurdity. They’re valuable because of it. In the long phalanx of history, genius always stands right next to foolishness – both refuse to accept that what’s “true” is necessarily what’s real. Both tear unlikely holes in our settled webs of cause and effect. Without the fools, the ones willing to introduce the patently absurd into the collective life of the mind, we’d never learn a thing about the world. There wouldn’t be anyone with enough imagination to ask the outlandish questions. There would be no one to reshape our conception of what’s ludicrous. So it’s not that religion is a panacea for our cultural ills. But with its pointedly fantastical tales and symbols, it might be the frontline defense against the genocide of the imagination.

_____

* Which turned out to be electrons in orbits around the nucleus. Until we realized we were wrong about that, too, and we replaced the electron orbits with nested electron shells, and replaced orbital trajectories with field equations that described electrons’ (probabilistic) locations. Facts, man. They’re slippery things.

† This view of religion puts pressure on my claim last year that religiousness can make people less creative. But I think creativity is throttled by too much rationalistic positivism just as much as by too much religious conformity.