Connor Wood

Religion is confusing, right? Why do people do these weird things, like lighting candles next to statues of gods, praying to deities with names like “Krishna” and “Jesus” and “Buddha Amitabha,” and pursuing master’s degrees in theology? Everyone has an opinion. Some people think that religion arose to explain the frightening natural world, and now that we have science to explain things, religion is obsolete. Others think that religion is a cynical tool for elites to keep the masses down. Fortunately, we don’t have to just rely on speculations. There’s a massive, growing body of literature on religion, and learning about it can help us understand what religion is and where it came from.

Last week, I focused on functionalist theories of religion – that is, theories that assume that religion plays a functional role in human societies and individual lives. This week, I’m continuing roughly in that line, but the theorists I’m featuring are more focused on how ritual shapes beliefs. Here in the post-Protestant West, we tend to assume that what really matters about religion is faith, or beliefs, particularly in spirits and gods (or God). But while faith is clearly important in religion, the modern focus on the contents of religious beliefs often misses the fact that these beliefs don’t come from nowhere. Our beliefs and our worldviews are shaped not only by what we’re told or what we read, but also by what we do. This is why ritual matters so much – it doesn’t compete with our beliefs. It gives rise to them.

The four thinkers below have massively advanced our understanding of how ritual and beliefs intertwine, and particularly how religion both creates and destroys metaphorical boundaries or “walls” – between tribes, between life stages, even between good and bad. As Durkheim from last week’s post argued, the boundary between what’s “sacred” and what’s “profane” is the anchor of any religion. Drawing on this distinction, our first thinker sheds light on how religion generates ideas like “clean” and “not clean,” or “pure” and “impure” – which are fundamental religious distinctions found in all cultures.

Mary Douglas

In last week’s theory-of-religion primer, I sketched sociologist Émile Durkheim’s influential argument that what a society considers “sacred” or “set apart” – its gods, certain myths, the Black Hills, whatever – is the linchpin that holds the culture together. For Durkheim, the sacred is opposed to the profane, or the everyday or commonplace. Anthropologist Mary Douglas (1921-2007) took Durkheim’s ideas more than a few steps further, generating a new theory of ritual and culture that has changed the entire course of religious studies. Criticizing Durkheim for assuming that his sacred/profane distinction only applied to “primitive” cultures, Douglas forcefully argued that all cultures – including supposedly rationalistic, Western societies – depended on such distinctions. In her influential book Purity and Danger, Douglas’s penetrating analysis of purity – as against dirtiness or impurity – showed how rituals help to identify certain things as “clean” and others as “not clean.” All cultures have such pure/impure distinctions, and they’re nearly always a central concern for religion. (Think Muslims washing scrupulously before prayers, or Christians donning white clothing before baptism.) In particular, Douglas’s studies among the Lele people of the Congo convinced her that what people believe about purity is a direct reflection of what they believe, ultimately, about the universe:

Among the Lele I found that rules of hygiene and etiquette, rules of sex and edibility fed into or were derived from submerged assumptions about how the universe works.

Douglas famously defined “dirt” as “matter out of place,” or stuff that isn’t where it’s supposed to be. So, for Douglas, religious ideas about purity and dirt play an all-important role in maintaining boundaries between things. Contamination is dangerous because boundaries are what make the entire universe possible – you can’t have good without bad, winter without summer, men without women.* Interestingly, Douglas’s ideas presaged recent studies showing that religious belief might actually prevent the passage of germs across cultural lines: by making people more conservative and less open to outsiders (that is, more concerned with cultural boundaries), traditional religion might be part of a “behavioral immune system” that keeps contaminants – both literal and figurative – at a comfortable distance from a community and the people who inhabit it.

Victor and Edith Turner

Victor Turner (1920-1983) was a British anthropologist whose interactions with the Ndembu people of subsaharan Africa allowed him to craft one of the 20th century’s most influential theories of ritual and religion. Informed by his studies of Western theater, Turner’s work hinged on a view of society that emphasized social processes, or “dramas.” Undoubtedly his most famous contribution to religious studies is the idea that two complementary social modes underlie all social processes: structure and communitas. “Structure” is the everyday network of roles and statuses that we all take part in at work, school, or the market – it’s when we call our instructors “Professor” and cops “Officer.” “Communitas” is when people step away from their everyday roles and titles, interacting with one another as pure equals. This is when our professor becomes “Bill” and the cop is just “Sandy.” Turner argued that communitas is what ritual is all about – by creating spaces and times that are “set apart” from everyday social structure (Mary Douglas and Durkheim, anybody?), ritual allows people to experience sheer, undifferentiated social unity and spontaneity. Importantly, it also allows people to transition between structural roles; in Turner’s model, communitas is necessary for “liminality” (a word that comes from the Latin limen – “threshold”), or a time when a person is in between social roles, neither one type of person nor the other. The archetypal example is puberty: not yet an adult, no longer a child. Ritual, Turner argued, intentionally creates liminal experiences in order to shepherd people from one social role to another. For instance, many African societies have puberty initiation rites, where young people are taken away from the tribe for days or weeks. During this time, they are in “liminal” space, and in “communitas” with each other – neither children nor adults, lacking economic responsibilities, occupying no social roles, and complete equals.

Interestingly, Turner pointed out that there was a cross-cultural connection between poverty, liminality, low social status, and communitas, arguing that people who were seeking communitas – that is, social equality and spiritual renewal – “often begin by minimizing or even eliminating the outward marks of rank…(and) approximate in dress and behavior the condition of the poor.” Which explains some things about the American counterculture.

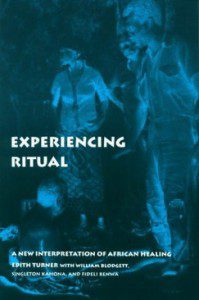

Turner’s wife, Edith (b. 1921) is an influential anthropologist in her own right. Her most famous work, Experiencing Ritual, is an important study of how religious healing rituals work among the Ndembu – by creating communitas through drumming, mildly psychoactive drinks, and song, the Ndembu enjoin spiritual influences to heal sick patients. But that’s not what’s really interesting. What’s really interesting is that these spirit-drumfests actually allow for the opening of boundaries between different levels of society. A person whose role is low-status might, through the ritual communitas experience, be enabled to express her grievances against higher-status folks in a way that otherwise would be impossible. In the Turners’ work, ritual and communitas make social boundaries – between high-status and low-status people, between men and women, and between older and younger – permeable. So is religion about creating and maintaining symbolic boundaries, or smashing them?

Adam Seligman

Both Mary Douglas and the Turners came to their understandings of religion through painstaking fieldwork with small-scale African societies. Now let’s zoom out. Adam Seligman (b. 1954) is a sociologist of religion whose work focuses on ritual and modernity. Similarly to Victor Turner, Seligman emphasizes a key distinction between two different major social modes: the ritual mode and the mode of sincerity. The ritual mode is formal, action-based, non-rational, collectivistic, and imaginative. The sincere mode is individualistic, “authentic,” word-based, rational, and private. Through ritual, humans generate “shared subjunctive worlds,” which are the communal, imaginative universes that focus on “as-if” ideas about how the world could be. For instance, the ritual action of saying “please” to a waiter creates a shared illusion that the waiter has a choice in whether to bring you more coffee (which, of course, he actually doesn’t). This is why the word “please” is polite – it lets the person on the receiving end feel pleasantly autonomous, even if actually he or she has no choice in whether to obey your request. So, for Seligman, social conventions like saying “please” and “thank you” are the ritual building blocks of everyday life – creating little flurries of illusions here and there, allowing the world to work smoothly.

Religion is this ritual process writ large. If saying “please” creates a momentary “as-if” illusion, then religion creates lifelong, even millennia-long, shared imaginative worlds, where “as if” dominates over “as is.” Seligman argues that this is how it has to be – a society that insists on relating to the world only as it is – that is, sincerely – will suffer from an inability to act adaptively, since correct action depends on imaginatively projecting plans and ideals into the future. Seligman accuses both liberal modernity and religious fundamentalism of relying too much on sincerity or “realism.” Ideally, sincerity keeps ritual from formalizing and rigidifying too much. All religious renewals and countercultural movements are thus rooted in sincerity, or the ability of the individual to clearly see the real truth, unfettered by the dogmas and empty rituals. But when taken to extremes, this sincere orientation leads both to empty materialism and blind religious fundamentalism – both of which overemphasize the individual and his or her “pure truth,” and downplay the vitality of living, imaginative ritual.

This was Part Two in a series of, I don’t know, five or six posts on theories of religion. In these posts, I’m sharing knowledge about respected theories and research on religion, as a way of showing that we don’t just have to speculate fruitlessly about religion – we can actually learn real things about it. Check back next week for more!

______

* Unless you are Hemingway