Theodicy is one of those odd theological words popping up. It is supposed to answer the problem of evil in a creation made by an omnipotent (all-powerful) and omnibenevolent (all-good) God against the clear evidence of evil in the world. It is a philosophical approach seeking to defend God’s providential care against the manifest indications that something is out to get us, and by any objective criterion, it is evil.

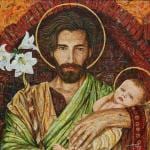

Why, if God is good, does He allow evil? Why save the baby Jesus and let the Bethlehem killings go forward? Could he not have saved both? Why does the Christmas Eve drunk go unscathed while the family of 5 he crashed into die?

That’s what theodicy seeks to explain.

That will take you in a lot of strange directions, but the Augustinian explanation, one form or another, seems to dominate.

Free will, said St. Augustine, that’s the problem. Most of our problem is from free will, starting with our primal Edenic forebears. Their first sin – distrust of God – is our sin and nobody else’s, and our sin messes with ourselves and everybody and everything else. The fabric of creation, through and through, is stained. St. Paul asserts the whole of the cosmos groans for redemption, for rescue, for relief as if in the pangs of childbirth (Rm. 8:22) and Augustine says that’s our fault. Thanks, Augustine.

But free will doesn’t answer everything. It handles a good part of everything, but not quite everything. What does free will have to do with cancer, unless that too is part of our primal distrust of God? Of course, as at least one theologian has it (featured in a column by a friend of mine), it ends up that “stuff happens.” You shrug your shoulders and move on, okay?

It has been examined with some greater speculation. The whole of it comes down to a few propositions, said to have been asked originally by a pagan philosopher, Epicurus (d. 270 BCE):

Is God willing to prevent evil, but not able? Then he is not omnipotent.

Is he able, but not willing? Then he is malevolent.

Is he both able and willing? Why is there evil?

Is he neither able nor willing? Then why call him God?

Epicurus wasn’t arguing against God (the Greeks often used “God” as a summary for all the gods and godlets). He wasn’t arguing a sort of atheism. He was dismissing the idea of divine providence. It is a question of whether God, in any sense, cares for creation. If He doesn’t, why worry about evil or good?

I don’t think the question of evil can be answered, nor is it satisfied by Augustine’s free will perverted by sin. “Why is there evil” is the wrong question from a Christian view. Evil just is, and inexplicable, finally. Like the guy said, “stuff happens.” In the chaos of random causality, all of us are potential casualties.

Yet amid all this “stuff,” I think we are entitled to ask of God, “What will You finally do about it?” If God is the “maker of heaven and earth,” then He is to some degree accountable, answerable to and for His creation. It’s a fair question.

I’m not the only one. There is an impatient strain of biblical prophets and psalmists demanding of God, how long will this go on before you get off your high throne and do something. Help your people. What will You do and when? If there were a customer survey available, I’m not sure how God would fair, 1 being poor and 5 excellent. If he has the answer to evil, it’s time to spill the beans.

Elie Wiesel (d. 2016) claims to have witnessed a rabbinical court that put God on trial in the in Auschwitz concentration camp. It is one of those stories that, if not true, ought to be. God was indicted for the suffering of the Jewish people, charged as a collaborator in murder. Witnesses were called, testimony was solicited, but in the end, the court was adjourned. It became a play, though an awkward one from critics and the plot itself left a verdict unspoken.

Then it came time for evening prayers. The rabbis adjourned and sang their prayers. The verdict was delayed. Evening prayers interrupted any resolution. But if there were a verdict, a sentence, would it look like Anthony Sacramone’s?

. . . our verdict – like Rome’s, like Jerusalem’s – is guilty. And their sentence is ours too: Crucify him. But make it quick. The Sabbath is coming. Pull him down quick. The guards are watching. Bury him quick. Darkness has fallen. “A sacrifice. A holocaust. And when a man sacrifices something, it must be the best. The most beautiful.” Roll the stone. Quick. The Sabbath is coming. Who was this Jesus? Didn’t you hear? Jesus was a Jew. A Jew before Pilate. Forsaken by God. Jesus was a Jew, a Jew before Torquemada. Forsaken by God. Jesus was a Jew, a Jew before Hitler. Forsaken by God. Jesus was a Jew, a Jew in Selma, a Jew in Sudan, a Jew in Orissa, a Jew in Tehran. And where is God? Quick. The Sabbath is coming. We’ll return Sunday. But to whom shall we go now? What do we do now? Now . . . we pray.

Russell E. Saltzman publishes every Tuesday and Thursday usually by noon Central Time. He can be reached on Twitter as @RESaltzman, on Facebook as Russ Saltzman, and by email: [email protected].