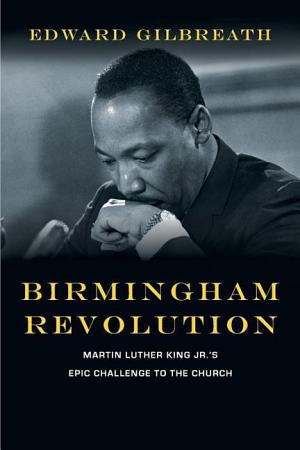

“Is another King book necessary?”

This is the question that Edward Gilbreath asks in the Acknowledgments at the end of his book Birmingham Revolution. Let me weigh-in with a decisive “Yes.”

This book’s contribution to the literature about Martin Luther King, Jr. meets a need in American Christianity and in America herself. This book reminds evangelicals (esp. white ones) that MLK was a true brother in Christ and it reminds secularists as well as liberal and progressive mainline Protestants of Mark Noll’s observation that the Civil Rights movement and “the religion of King and his associates was always more than just black evangelical revivalism, but it was never less.”

Gilbreath also seeks to re-radicalize Rev. Dr. King. Over the years, time, and a variety of conventional social forces have worked to reduce this great Christian social activist to being milquetoast, genteel, warm and cuddly “Santa Claus” type figure. Gilbreath reminds us that King was a true extremist for the sake of love and justice whose activism extended far beyond his dream of racial harmony. Gilbreath’s book provides a concise biography of King’s life leading up to his ministry at Dexter Avenue Church in Montgomery, AL and helps the evangelical community to more fully recognize Rev. King as a full brother in Christ. As a progressive Christian from a mainline Protestant tradition, I’ve never thought of Dr. King as not being a Christian (indeed, just the opposite, I’ve viewed him as an exemplary one), but this book helped me to realize more keenly how many evangelicals in the U.S. have had “a strained relationship” with MLK. Sadly, I’ve learned that this is an understatement.

The author doesn’t engage in revisionist history in his treatment of King. He eschews rose tinted glasses or hiding King’s skeletons and shadow sides. He does, however, pointedly remind us of the deep, authentic, and ardently Christian motivations and commitments of this great leader.

I learned some new things upon reading Birmingham Revolution. I learned that Claudette Colvin, is the name of the teenager who “preceded [Rosa] Parks by nine months in her refusal to give up her seat on a segregated bus.” I learned that “Birmingham was [Rev. Fred] Shuttlesworth’s house, King was just visiting.”

I learned how dire things got for King and those engaged in “the Birmingham campaign.” I learned that Albany’s police chief Laurie Pritchett studied King’s nonviolent methods and used them against King, telling his officers, “We’re going to out–nonviolence them.” And that “Bull” Connor learned from Prichett’s playbook and applied those lessons to Birmingham – almost causing King’s occupation of Birmingham to fizzle out, leaving the SCLC broke, and thus derailing the entire Civil Rights movement. Gilbreath vividly shows how the showdown in Birmingham was the main event in the multi-round prize-fight for civil rights for all American citizens.

One of the true gifts of Birmingham Revolution was how Gilbreath humanized the eight clergymen who wrote that infamous letter to the editor that King responded to with his famed letter from a Birmingham jail. Gilbreath showed how those religious leaders were not overtly racist or mean-spirited, but rather, were local pastors, area bishops, and a rabbi who genuinely cared about their people. They were concerned that King’s efforts to get their citizens to become actively engaged in ending segregation in such a visible manner was effectively leading the people of their flocks into temptation; i.e., the temptation to retaliate against those protesters with violence. They were also concerned about the well-being of those protesters. To a large extent, they were being understandably pastoral in their appeal for “gradualism.”

Gilbreath is at his literary best as he shares the riveting back-story behind King’s letter of response from that jail. He has readers palpably feeling King’s visceral rage and righteous indignation and see the theological wheels spinning in King’s mind in that jail cell as he took pen to paper to scrawl-out that potent and passionate pastoral epistle. As Gilbreath puts it, this letter was the culmination of King’s life and was “his real doctoral thesis.”

Ironically, even though the focus of this book is on King’s becoming emboldened and bluntly rebuking gradualism –- saying “the time is now!”– the author seems to pull his punches. Gilbreath lets readers connect their own dots. This might be wise politically, and even pedagogically, but I was still surprised by the contrast.

Gilbreath all but invites the Christian community to adopt King’s Letter from a Birmingham Jail as part of our canon – to make it part of the Bible. No, he didn’t actually say those words or posit an overt argument for that, but he provides a compelling momentum and flow for us to sail upon – and mentions that “others” posit such notions and think such thoughts (including me).

I appreciated Gilbreath’s King-like diplomacy and tact in encouraging the expanded application and full realization of King’s “Dream” of the “beloved community” beyond matters of race.

The author identifies part of the reason that many evangelicals have been slow to embrace King as their perception of his focus upon the Social Gospel – and, their perception that he wasn’t sufficiently concerned about personal salvation. In response, Gilbreath shows King’s very personal experiences with the living Christ and how that was the motivation for King’s work.

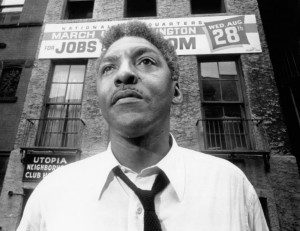

Gilbreath indicates that many evangelicals are finally getting it by applying Rev. King’s vision of social justice to the contemporary issue of immigration reform. I’ll add that a growing number of evangelicals today are also applying that vision to the social ills of sex slavery and human trafficking – and increasingly, to the environmental crisis of human-aggravated global warming and our utter failure to be good stewards of God’s Creation. However, Gilbreath failed to mention the obvious linkage to LGBTQI issues. He only mentioned Bayard Rustin in passing. Referring to him quickly as “controversial King adviser” – effectively leaving the architect of King’s largest rallies still in the closet.

To this progressive Christian’s eyes, Gilbreath dropped the ball in failing to name the elephant in our nation’s living room — the abundantly clear parallels between the racial segregation and Civil Right’s movement of the 1950’s and ‘60’s to the civil rights movement of our day – gay rights. As King’s late wife Coretta put it,

“Lesbian and gay people are a permanent part of the American workforce, who currently have no protection from the arbitrary abuse of their rights on the job. For too long, our nation has tolerated the insidious form of discrimination against this group of Americans, who have worked as hard as any group, paid their taxes like everyone else, and yet have been denied equal protection under the law.”

“I believe all Americans who believe in freedom, tolerance and human rights have a responsibility to oppose bigotry and prejudice based on sexual orientation.”

“I still hear people say that I should not be talking about the rights of lesbian and gay people and I should stick to the issue of racial justice. But I hasten to remind them that Martin Luther King Jr. said, ‘Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.’ “

“ I appeal to everyone who believes in Martin Luther King Jr.’s dream to make room at the table of brother- and sisterhood for lesbian and gay people.”

“We have to launch a national campaign against homophobia in the black community.”

“Homophobia is like racism and anti-Semitism and other forms of bigotry in that it seeks to dehumanize a large group of people, to deny their humanity, their dignity and personhood. This sets the stage for further repression and violence that spread all too easily to victimize the next minority group.”

“Gays and lesbians stood up for civil rights in Montgomery, Selma, in Albany, Ga. and St. Augustine, Fla., and many other campaigns of the Civil Rights Movement. Many of these courageous men and women were fighting for my freedom at a time when they could find few voices for their own, and I salute their contributions.” Source. See also.

Birmingham Revolution seeks to help evangelicals integrate the values and teachings of MLK; to help Gilbreath’s fellow evangelicals reassess, appropriate, and assimilate the profoundly Christian holistic gospel that King taught, lived-out, and modeled all the way to his death.

While I can appreciate that the author may’ve felt that bringing up the obvious connections to gay rights would detract from his mission of bringing evangelicals ‘round to fully appreciating MLK, his failure to name those connections ironically reminds me of the gradualism that Dr. King railed against in his letter from that jail.

Gilbreath didn’t quite name the racism of his evangelical community, but he did allow some of the people he interviewed to name theirs. This was probably a wise move. Racism is still a touchy subject today and, sadly, there’s still need to walk on egg shells.

Perhaps IVP publishing Birmingham Revolution is a sign of progress and yet another instance of the religion of the oppressor being held up by the oppressed to help that religion be its true self. As Gilbreath puts it “..it occurred to me that perhaps one of the reasons King’s voice now resonates more clearly with evangelicals is because the Baptist preacher was speaking a more authentic version of their language all along.”

xx Roger

This book is featured at the Patheos Book Club this month.

Rev. Roger Wolsey is an ordained United Methodist pastor who directs the Wesley Foundation at the University of Colorado at Boulder, and is author of Kissing Fish: christianity for people who don’t like christianity

Click here for the Kissing Fish Facebook page