How I Tried on Liberal Christianity and Why It Didn’t Fit

You know the experience. You see a sweater (or other piece of clothing) at a store and you like it a lot and you really want to own it. It’s not exactly your size, but you convince yourself maybe it will shrink or stretch and you buy it and try wearing it during the first cold days of winter. You like it a lot, well, sort of. It’s fashionable, “cool,” attracts compliments. But even after several wearings and washings it just doesn’t fit. Either it’s too baggy or it’s too tight. Finally, you do what you suspected you might have to do when you bought it—give it away.

I grew up in what many people would consider a very fundamentalist denomination. We did not call ourselves “fundamentalists” because fundamentalists in our region were those dispensationalist, cessationist, King James Bible only, hard shell Baptists (and others like them). We were Pentecostals but we preferred to call ourselves “Full Gospel.” And we didn’t have the systems of theology or lengthy doctrinal standards many fundamentalists had and have. But, still, nevertheless, we were fundamentalists in our basic approach to the Bible (literalism), attitude toward modern, secular culture (anti-), and harsh disdain of “mainline churches” (“nominal Christians” at best).

Our two favorite “study Bibles” were the Scofield Reference Bible and the Dake’s Study Bible. In college I learned to discard those and use a “modern translation” (both of those were and are KJV)—the American Standard Version. I was shocked by many things I learned in “our college” including that Moses did not write the Pentateuch. But during my college years I never really encountered true liberal Christianity. I heard of it, but the main name given allegedly associated with it was Karl Barth.

I enrolled in a moderately evangelical Baptist seminary and it was a wonderful experience. I was sad to graduate. There I learned that Barth was not liberal and our main textbook for systematic theology was Emil Brunner’s three volume Dogmatics. During seminary I was introduced to the writings of George Eldon Ladd (New Testament), Donald G. Bloesch and Bernard Ramm (systematic theology), Berkley Mikkelsen (hermeneutics), and other great “lights” of moderate-to-progressive evangelical biblical studies, theology, and ethics of the 1960s and 1970s. On my own I picked up and read Dietrich Bonhoeffer, G. C. Berkouwer, Jürgen Moltmann, Wolfhart Pannenberg, and other “big names” in Protestant theology outside of American evangelicalism. I took an independent-guided study with my academic advisor Dr. Ralph Powell of radical theologians such as Paul van Buren, John A. T. Robinson, Harvey Cox, Thomas Altizer, William Hamilton and others. I stepped outside my own seminary and took two courses through a local extension of Luther Seminary—one about process theology and the other about liberation theology. Both were taught by proponents of those theologies. Through those courses I encountered the writings of John Cobb and Gustavo Gutierrez and other process and liberation theologians.

*Sidebar: The opinions expressed here are my own (or those of the guest writer); I do not speak for any other person, group or organization; nor do I imply that the opinions expressed here reflect those of any other person, group or organization unless I say so specifically. Before commenting read the entire post and the “Note to commenters” at its end.*

I spent hundreds of hours in the seminary library reading magazines and journals and especially Christianity Today, Christian Century, The Post-American (which later changed its name to Sojourners), Agora (a short-lived independent journal of enlightened Pentecostal opinion that was shut down by the Assemblies of God), and The Other Side. My mind began to change; it began to open to new ways of thinking about Christianity.

During my doctoral studies in Religion at university I had professors of very different Christian persuasions and traditions: Eastern Orthodox, liberal Methodist, moderately evangelical/neo-orthodox, progressive Baptist, Roman Catholic, German Lutheran, and unknown (a philosophy professor). I joined the only American Baptist (ABCUSA) church in the city which happened to be very liberal. But I served on the pastoral staff of a Northern Presbyterian church (United Presbyterian). As part of my Ph.D. studies I studied with theologian Wolfhart Pannenberg in Munich where one of the only other American students was Philip Clayton. We spent a lot of time together in heavy discussions of Panennberg’s theology and theology generally.

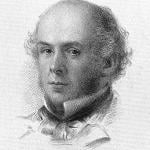

During my Ph.D. studies I read voraciously including the main writings of Karl Rahner, Mircea Eliade, Paul Ricouer, Hans Küng, David Tracy, Hans Georg Gadamer, Immanuel Kant (an entire semester seminar), et al. And I met and spent time with Dietrich Ritschl, grandson of the great liberal theologian Albrecht Ritschl.

At some point I began to read on my own Marcus Borg and John Shelby Spong—among other liberal, mainline Protestant theologians. I decided that I needed to “try on liberal theology” just to see if it fit me. My two churches—American Baptist and United Presbyterian—were liberal, but my wife and I attended a Vineyard church on Sunday evenings—to stay in touch with our Pentecostal-charismatic-renewalist heritage. We became very good friends with the pastor who later went on to be the national director of the Vineyard.

Jumping ahead a few years—past my extremely troubled two years on the faculty of Oral Roberts University which was then (early 1980s) trying to become a United Methodist university and seminary while keeping its charismatic “touch.” I finally arrived at the college and seminary to which I had felt called ever since my seminary days (if not before)—Bethel in St. Paul, Minnesota. Because my wife and I were members of an American Baptist Church in Oklahoma (the only one in that state then) we joined an ABCUSA church in the Twin Cities. Although Bethel was and still is moderately evangelical, our church was very openly liberal. A former pastor was Edwin Dahlberg who had served as Walter Rauschenbusch’s teaching and research assistant during WW1. He left his stamp on the church.

At church I heard sermons, Sunday School lessons, and Bible studies informed by liberal Protestants like Marcus Borg and John Shelby Spong (with whom I was familiar through reading their books). I would say the church was probably one the great American liberal theologian and pastor Harry Emerson Fosdick would have enjoyed attending. (But he was dead by then.) That was the kind of church it was—“evangelical liberal.” The pastor was a former Southern Baptist who did not believe in miracles or demons (among other things). I came to doubt whether he believed in anything supernatural. The whole emphasis of the church was on social justice and spiritual formation. Doctrine played virtually no role at all, whatsoever.

To a certain extent I internalized liberal theology while not teaching it. I seriously “tried it on” to mix metaphors. I gave it my best shot. I read great texts of liberal theology from Schleiermacher’s Christian Faith to the systematic theology of William Newton Clarke to Fosdick to Shailer Mathews to Borg and Spong. I regularly attended a society of theologians that met twice annually in Chicago; most of its members were liberal theologians who taught at the various seminaries clustered around the University of Chicago. I well remember liberal theologian Gary Dorrien coming down from Kalamazoo College (Baptist) to talk about his project of writing a three volume history of liberal theology in America. (He later moved on to Union Seminary in New York.)

At these day-long theological confabs I met and had personal conversations with Bernard Loomer, Paul Knitter, Philip Hefner, Anna Case Winters, and a host of other theologians I would classify as liberal. Eventually I was elected president of the society for one year.

During my fifteen years at Bethel I organized several “liberal-evangelical dialogue” events—including one memorable one with a professor of theology at a liberal UCC seminary. It did not go well. I took my classes to hear leading liberal theologians like Letty Russell at that UCC seminary and liberation theologians like José Miranda (Marx and the Bible) at a Lutheran college. I entered into correspondence with Marcus Borg and had my students read one or two of his books. I taught an elective course on feminist theology where we read Elizabeth Johnson’s She Who Is and engaged in correspondence with her.

I have read numerous books about liberal theology including Dorrien’s three volume history of American liberal theology and numerous books by liberal theologians from Washington Gladden to Adolf von Harnack to Henry Churchill King to Douglas Ottati (not to mention almost everything written by Borg and Spong).

I tried on liberal Protestant theology; it didn’t fit. I never felt comfortable in it. Some will say that’s because of my extremely conservative, pietist-Pentecostal upbringing. I will gladly admit that especially in my youth I had extremely powerful, life-transforming spiritual experiences that liberal theology could not explain to my satisfaction. But mostly I felt that liberal Christianity was thinly veiled secular humanism with a Christian veneer (to mix metaphors). After everything was removed that is supposedly inconsistent with modernity or postmodernity, nothing of classical, historical Christianity was left. But most of all, I suppose, I felt that liberal Christianity lacked transforming power. It was and is shallow, weak, almost empty. And I noticed that most liberal Christian churches and denominations were dying. I did not see any future in it.

Although I would not agree with much of fundamentalist J. Gresham Machen’s theology (especially his Calvinism) I have to agree with him and humanist Walter Lippman that liberal Protestant theology is not authentically Christian. And I came to the conclusion that there is something disingenuous about most liberal theologians and churches calling themselves “Christian.” Most recently I re-read Peter C. Hodgson’s Liberal Theology: A Radical Vision (2007) and realized again why liberal Christianity does not fit me. Toward the end of the book, after denying the orthodox doctrine of the person of Jesus Christ (p. 51) Hodgson writes that “God…becomes incarnate in Christ and other savior figures” and affirms the saving power in all the major world religions. He clearly did not (when he wrote this book) believe in anything like the traditional, orthodox “Chalcedonian” concept of the incarnation. For him, Jesus Christ was simply “the revealer of divinity and mediator of reconciliation, filled by the power of the Spirit to manifest love and endure anguish” (p. 51) But clearly, for Hodgson, Jesus was only that for Christians and not for everyone. He redefined the Holy Spirit and the Trinity along Hegelian lines, not as an eternal divine community of three co-equal persons but as “moments” in the divine process of self-actualizing through history.

I would never dare to judge Peter Hodgson’s or any other liberal theologians’ (or anyone’s!) salvation. That is solely up to God. However, I will dare to judge the theology articulated in that book not authentically Christian. In fact, in my opinion, for whatever it’s worth, it is a betrayal of true Christianity. Is Hodgson himself a Christian? I have no opinion about that as I do not know him well enough even to suggest an answer. I can only judge his theology—as expressed in this book. And I find that theology to be typical, with some exceptions, of liberal Protestant theology as a whole.

What is the crux of the matter? Christology. In liberal theology, however it is expressed, Jesus Christ is only a human being, different only in degree from other great prophets and spiritual revealers of God, not different in kind. Most tellingly, he did not preexist his birth from Mary (and according to Spong possibly from a Roman centurion) except in the mind of God. The very heart of true, historical, classical Christianity is the doctrine of the incarnation of God in Jesus Christ, as Jesus Christ, and the reality of Jesus Christ as God and Savior, the only savior of humanity.

Liberal Christianity cuts the cord of continuity between classical, orthodox Christianity and itself. Liberal Christianity is consistent with early (and sometimes later) Unitarianism, but not with Christianity. To be fully honest, liberal Protestant Christians should stop calling their theology “Christian” and call it “unitarian” or even “religious humanist.”

*Note to commenters: This blog is not a discussion board; please respond with a question or comment only to me. If you do not share my evangelical Christian perspective (very broadly defined), feel free to ask a question for clarification, but know that this is not a space for debating incommensurate perspectives/worldviews. In any case, know that there is no guarantee that your question or comment will be posted by the moderator or answered by the writer. If you hope for your question or comment to appear here and be answered or responded to, make sure it is civil, respectful, and “on topic.” Do not comment if you have not read the entire post and do not misrepresent what it says. Keep any comment (including questions) to minimal length; do not post essays, sermons or testimonies here. Do not post links to internet sites here. This is a space for expressions of the blogger’s (or guest writers’) opinions and constructive dialogue among evangelical Christians (very broadly defined).