“Living Theology: Knowing and Following Our Resurrected Lord”

This is a talk I gave at the recent MissioAlliance Gathering in Alexandria, Virginia. The forum topic was “Living Theology: Knowing and Following Our Resurrected Lord.” (The theme of the Gathering this year was “Resurrection Life.”) I was one member of a panel; each member gave his or her own talk on the topic. I was the first to speak; two panel members used some of their time to disagree with my talk. After the “talk” (essay) below I will respond to their critiques. One said that she thought it ironic that her talk—on pacifism—followed immediately mine. (Obviously she thinks that any talk about “warfare” is somehow contrary to pacifism.) Another said that he disagrees with me about Christians being called to go out into the world to engage evil powers and deliver people from their domination. According to him, I guess, Christians are only called to do this within the confines of the church. I will respond to these two objections to my essay (now a blog post) immediately following it:

My MissioAlliance forum presentation on “Living Theology: Knowing and Following Our Resurrected Lord”:

“Living theology” is many things, but chief among them is spiritual warfare. Because of the resurrection of Jesus we know and confess that “Jesus is victor!” But, as we also know, that does not mean that everything is as God wills. The world is still deeply disordered by dominations of many kinds that keep people enslaved. “Living theology,” “spiritual warfare,” is resurrection theology in action; it is the body of Christ seeking in the power of the Holy Spirit, the gift of the risen Jesus, to free men, women and children from every bondage that enslaves them. The enslaving “powers and principalities” are defeated but still fighting. The resurrection calls us into battle against them.

Prophet Christoph Blumardt wrote that

What matters is that people are delivered, cut free, and torn away from false masters, from…domination. God’s sovereignty opposes human dominion. That is the point, and that is why the struggle in us and around us is so hard. If God’s kingdom exists only to give us joy in heaven, if we were meant simply to put up with the way things are and accept all laws as they are, it would be an easy matter. Then all we would have to do is accommodate ourselves to the world. We could stupidly accept that the our whole history of war and hatred is part of God’s order, that violence quite naturally belongs to human life…. There thus arises a world god, whom the Savior calls the prince of this world. He claims our allegiance. But Christ, too, claims our service; he rises up in the name of God and shapes life on earth in opposition to that power that has established itself over the centuries. This is why it is such a struggle for God’s kingdom to advance on earth.[1]

“Living theology,” then, must include, perhaps even as its first task, exposing the enslaving, de-humanizing powers of the world system of domination, ministering deliverance to its victims, and developing a radically alternative form of life that is the true church, the outpost, the prolepsis of the coming perfect reign of God which is total freedom.

We “normal evangelicals” have become far too complacent about the demonic, the natural and supernatural powers that dominate and enslave people. We fear being considered fanatics if we engage in spiritual warfare either through political protest or deliverance ministry through prayer. Our beloved New Testament, however, is absolutely filled with narrative descriptions of such—in both the gospels and the Acts of the Apostles. Our beloved Old Testament prophets specialized in speaking truth to power—about justice for the poor and oppressed. The whole Bible teems with imperatives to the people of God of all times and places to not only pay lip service to the lordship of God but to implement the lordship of God among ourselves and to denounce everything that contradicts it and announce the Kingdom will of God for freedom to be human. Jesus and the apostles were not satisfied, however, to denounce and announce; they engaged the powers of evil in what John Wimber called “power encounters.”

Based on the resurrection of Jesus that announces Jesus as victor (!) we must stop reducing our Christianity to “learning and serving” and begin living the theology of the conquering Christ in acts of deliverance that foreshadow the perfect freedom of the coming Kingdom of God. Living theology founded on the resurrection means nothing less than revolution against the de-humanizing, demonic powers of domination that still keep people loved by God and for whom Christ died and rose again in chains.

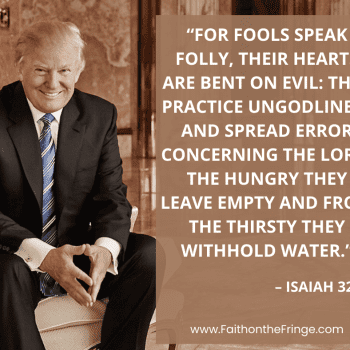

This living resurrection theology of freedom must be extended beyond the realm of human freedom to liberation of the earth from the corruptions of human civilization. That means we must stop being soft about environmentalism and say a definite “No” to those among us who deny what is happening to nature, the home God has given us that he intends to liberate from bondage to decay. Christian environmentalism must become an added dimension to spiritual warfare. Deniers of the danger must be denied a voice among us and we must step boldly forward to protect God’s good creation.

Please understand that, like Blumhardt, I am not talking merely about social work or political activism on behalf of an ideological agenda devised by worldly powers. I, like Blumhardt before me, am talking about engaging the evil powers and principalities that rule this fallen world system with spiritual force. This takes the courage of actions based on convictions that will inevitably result in some unfortunate or perhaps fortunate departures from our ranks. A smaller but more theologically correct and spiritually effective church is better than a Christian army without a clear vision or battle plan. We must decide who our enemy is and use every spiritual power given us by God to defeat it. Jesus is victor! We must join him in his final defeat of evil with resurrection power. (End of panel presentation)

Now I will respond to the two other panel members’ critical responses.

First, nothing about biblical spiritual warfare or what I said stands in any tension with Christian pacifism. Christian pacifism appeals to the teaching and life of Jesus; Jesus engaged in spiritual warfare. Christian pacifism opposes Christian use of deadly physical force; Christian spiritual warfare does not use deadly physical force. Christian spiritual warfare, as I described it (following Blumhardt) has nothing to do with physical violence and it is doubtful that its practices could ever be called violent in any ordinary sense of the word. The panel member who suggested that her Christian pacifism might be in tension with my description of spiritual warfare emphasized “reconciliation” as the most important practice of “living theology.” I certainly agree that reconciliation among people is an important practice of living theology. However, I would put that under the umbrella concept of spiritual warfare—opposing powers and principalities that tear people apart and pit them against each other. Ironically, then, Christian pacifism (including the practice she mentioned of “peacemaking teams”) is a form of spiritual warfare. I believe many Christian pacifists misunderstand “warfare” in the term “spiritual warfare.” Like “Onward, Christian Soldiers” (banned from many mainline Protestant hymnals due to a misunderstanding of its message as promoting physical war), “spiritual warfare” has nothing whatever to do with literal war or violence. And I assume even the Christian pacifist (a woman Mennonite minister) on the panel would not regard the biblical injunctions for Christians to engage in spiritual warfare as something to be ignored or cut out of Scripture. (I refer, for example, to Matthew 10—which I will mention below in response to the second critic of my talk.) I suppose one response (that I anticipate appearing here) is that “warfare” has become so closely connected in most people’s minds with physical violence, death and destruction, that it is best to drop the term altogether. I disagree—insofar as we qualify it with “spiritual.” Virtually every biblical and theological word is essentially contested in our pluralistic and largely post-Christian society. I do not believe in dropping everything of the “language of Zion” just because of widespread ignorance about its meaning. The language of spiritual warfare is so deeply embedded in the Bible that to simply drop it because it might be misunderstood is to alter Christian tradition at its very roots. A deeply committed Christian pacifist can and should engage in spiritual warfare in its New Testament meaning.

Second, in response to the other panelist, the New Testament itself includes commands to engage in and examples of spiritual warfare against “powers and principalities” outside the church. He argued that Christians are not called to go out into the world (presumably meaning outside the confines of the church) to deliver people from bondage to the powers and principalities that oppress them. Really? Before even mentioning the New Testament, I would ask if he seriously thinks Christian involvement in fighting against human trafficking is wrong. Of course not. But, given my description of spiritual warfare, fighting against human trafficking is a form of spiritual warfare. I assume he was focusing, though, on “deliverance ministries” in the common sense of exorcism which I do include under spiritual warfare. But even then, Jesus certainly did not limit his deliverance ministry, not did the apostles in Acts, to demonized people who came into the circle of Jesus’ disciples, the synagogues or the churches. The same is true with Jesus’ and the apostles’ healing ministries. Matthew 10 is a locus classicus of Jesus’ commission to his followers to engage in spiritual warfare outside the confines of religious organizations. I also regard Matthew 16:18 as support for my contention that “living theology” includes going out into the world to engage in spiritual warfare. What else could “the gates of hell” not “prevailing” against the church mean? The imagery used by Jesus there is clearly the church battering down the “gates of hell.” What are the “gates of hell” there, in Matthew 16:18? I would say they are all the powers and principalities, literal evil beings and social systems, that oppress and enslave people. It’s one thing to urge caution in how Christians engage in spiritual warfare outside the confines of the church; it’s another thing to suggest that Christians ought never to engage in spiritual warfare or even deliverance ministries outside the church. In fact, I suspect had we had more time the critic and I would have found greater agreement than perhaps audience members thought existed between us.

The background “point” of my talk about “living theology” as engaging in spiritual warfare, very broadly defined, is my constant question to my fellow American evangelical Christians (and other kinds of Christians in America especially). That question is: Have we not demythologized and “normalized” our Christianity so that it is not even recognizable as New Testament Christianity? What would the apostles think of us? How can we read the Acts of the Apostles and reconcile their “living theology” with ours? Cessationism is, of course, one way. But even most Christian cessationists believe in spiritual warfare—elsewhere (not here in “civilized America”). I am looking for New Testament Christianity in twenty-first century America and having difficulty finding it. Most of those (churches and ministries) that claim to have retrieved it and practice it seem extremist and fanatical to me. But maybe that’s just because I’m an Enlightenment-influenced, modern person.

The great irony I see in today’s Christianity is our American evangelical fascination with “Global South” (what used to be called “Third World”) Christianity which engages in spiritual warfare and believes in an invisible world of spiritual powers that Christians ought to oppose with all might and spiritual force. The irony is that we applaud it “down there” and “over there” but don’t want it here. We still think that we, America, are so “civilized” that we don’t need what they have. They are so “uncivilized” and “primitive” that they need what we don’t. This strikes me as an especially pernicious form of American exceptionalism and cultural accommodation.

[1] Christoph Friedrich Blumhardt, The Gospel of God’s Reign: Living for the Kingdom of God, trans., Peter Rutherford, Eileen Robertshaw, and Miriam Mathis, eds., Christian T. Collins Winn and Charles E. Moore (Eugene, OR: Cascade Books, 2014), 17.