First published at By Their Strange Fruit

Our God is a multicultural God. We see this in the Trinity. We see it in whom God chose to write the scriptures. We see it in the people Jesus spent His time with. We see it in the early church. We see it in verses like 1 Corinthians 12:12-31 and Revelations 7:9. To worship in such a setting is a great blessing that reveals the fullness of who our God is. I believe in the multicultural Church.

But like so many of God’s blessings, we often don’t deserve it. We fall short. We mess it up. When a white man violated the sacred space of Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, he boldly demonstrated why God’s vision for the multicultural church is still so far from our grasp. His violence reminded Black Christians that nowhere is safe, not even their church home. What he did was unconscionable. But in many smaller ways, white Christians send a similar message every single day.

You see, one of the best arguments I’ve heard against the multicultural church is the need for sanctified space for those of God’s people who are oppressed, marginalized, or in the minority. All through the week people of color are under the white gaze, immersed in white culture, navigating white power. This takes a great social, emotional, and spiritual toll, and it is important to have a reprieve–a day of rest– if only once per week, in which to fellowship and worship with folks that share your lived experiences.

Historically, the Black church has been such a refuge, allowing for this essential, sacred communion. It’s where folks can be themselves, worship as they desire, talk about what is relevant, raise up brilliant leaders…all apart from the oppressive gaze of white supremacy. Indeed it is its role in such subversion that is one of the reasons why Emanuel AME was such a symbolic and grievous target.

And the importance of such a setting is also a strong argument against the multicultural church. If we, as the Body of Christ, are to come together in diverse and unified worship, it will require tremendous and disproportionate sacrifice on the part of Christians of color.

The multicultural church comes at a great cost for the oppressed and the marginalized, much greater than for those coming from power and privilege. To be sure, white folks will have to sacrifice their comfort and preference to be a part of multicultural worship. But in contrast, Christians of color end up sacrificing their rest, their privacy, their autonomy, their self-care, their safety, their sanity, indeed sometimes their very humanity.

The multicultural church is a wonderful vision, but on June 17th, 2015, nine beautiful saints paid the ultimate price for it. By the grace that Christ taught, into their holy space a stranger was welcomed. And he killed them.

While it may not always result in direct and immediate death, the ongoing oppression of people of color (even and especially in houses of worship) is emotional, spiritual, and physical violence acted upon them. The consequences are long lasting. The need for sanctuary is real. Thus, there is a strong argument for mono-ethnic and mono-racial churches.

If churches do enter into a journey of multicultural worship, it is essential that safe refuge be available for congregants of color. This is also why it is important that when such endeavors are undertaken, they not ultimately be headed by white pastors and leaders (and they so often are). It’s why we must hedge toward the marginalized culture in planning worship services and events, rather than compromising squarely in the middle. Because there is no ‘happy medium’ when one group is so disproportionately abused.

After tragedies like these, I often hear it suggested that white Christians go visit Black churches for a Sunday or two as an act of reconciliation. But please consider that this act may be perceived as an invasion rather than as a gesture of love. Worship can begin to feel instead like cultural tourism, one that once again centers whiteness for its own edification and entertainment.

No doubt, it is good to displace one’s self from majority and comfort. It is good to be led by preachers and teachers of color. If invited, please do join a choir or bible study that affords these opportunities. If invited, please do go with your friend to their Black church. If invited, please do embark on the complex journey that is multicultural worship.

But I reject the notion that that white people’s colonization of Black space is the path to God’s multicultural justice and reconciliation. Indeed, too often it is simply a means of assuaging our guilt, a sacred culture co-opted for white people’s own sense of redemption.

A similar principle applies privileged folks’ moving into hard-living neighborhoods, often with a sense of saviorism that is difficult to combat. I say this, knowing the popular values of relocation and incarnation, and having myself moved to the block several years ago. Sometimes it’s good. Sometimes it works. But these are often acts of colonization, rather than of reconciliation (see also, Christena Cleveland’s ‘Urban Church Planting Plantations‘)

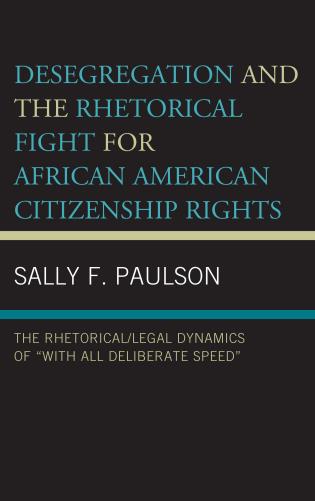

Studies show that most multicultural churches tend to be culturally more white than anything else. As power and “default” biases creep into our sanctuaries, racial hegemony kicks in (things to notice: how often does the choir sing? how is the offering collected? How long is the service? How long are the songs? What is the style of preaching?). Too often we are simply perpetuating the cultural dominance of the world around us under the guise of reconciliation.

I do love the multicultural Church. I believe it is ultimately where God is calling us as a Body to be. But at what cost? And for whom? We must indeed be prepared to make great sacrifices if this experiment on earth is to succeed. White people will need to sacrifice greatly. But it will always be Christians of color that bear the greatest burden. For Emmanuel AME the hope of a reconciled world cost them their lives.

Katelin Hansen is the editor of By Their Strange Fruit; a blog devoted to facilitating justice and reconciliation across racial divides from a Christian perspective.