In a recent interview, Mandip Gill (the actress who plays Yaz on Doctor Who) was asked: “If you could go anywhere in the TARDIS, where would you go?”

Her answer was, “I would go to the beginning of time and see how the world really was created!”

That seemed worth mentioning, before proceeding to talk about this week’s episode of Doctor Who, “Arachnids in the UK.” The episode does not have nearly as prominent religious themes as another famous episode with giant spiders, the final episode of the Jon Pertwee era, “Planet of the Spiders.” Looking back for my earlier post about the episode, I discovered that it also made a list of the “Top Ten Stories of Doctor Who with Religious Elements and Themes” on another Patheos blog, that of Henry Karlson.

The Doctor returns her friends to Sheffield half an hour after they left – which explains why Yaz hasn’t received any messages on her phone, but also shows why Doctor Who is a nice symbolic illustration of the experience of travel even on Earth. We return to the place we came from, and it seems not to have changed at all, while (as the Doctor tells her friends at the end of the episode, when they ask if they can continue to travel with her), “You’re not going to come back as the same people that left here.” That experience of reverse culture shock would surely be more disconcerting if one had previously been to alien worlds and to witness Rosa Parks sparking a major moment in the civil rights movement, but the same can be said even if you go live in another country for an extended period. I highly recommend it.

The Doctor makes like she is going to leave, but everyone seems to share the desire not to say goodbye. And so when Yaz invites the Doctor for tea, everyone is happy. As the Doctor tries bungling attempts at small talk, she explains that she is socially awkward, still trying to figure herself out.

Yaz’s father has been gathering evidence of some strange substance seeping into their building, which he says is proof of a conspiracy. The Doctor says, “I love a conspiracy.” He makes pakora. For some American viewers, a British family with Pakistani roots and Islamic art on the walls is the closest they have come to international travel. Yet there are familiar elements, such as Yaz’s tensions with her sister (which lead the Doctor to quip about sisters and say “I used to be a sister…”).

Eventually we get to see what the title of the episode ensured we would expect: there are giant spiders around. In discussing the strength of spider webbing (which is why research was being undertaken to breed larger spiders) the Doctor mentions that she and Amelia Earhart had had to deal with a very large spider web and discovered that it could indeed stop a plane in flight. Science fiction allows one to take such abstract facts and turn them into story.

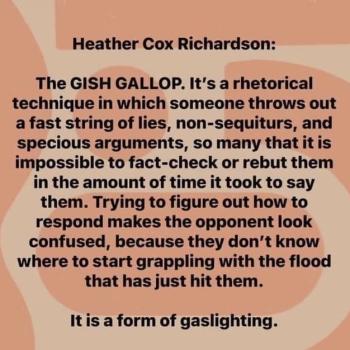

Early in the episode we had been introduced in the briefest of fashion to Jack Robertson, an American businessman that we later learn might run for president in 2020, mainly because he hates Trump. While everyone else knows who he is, the Doctor doesn’t (and asks whether he’s that Ed Sheeran she’s been hearing so much about). Robertson struck me as too much of a caricature, a cardboard cutout villain who lent no depth and so whose callous actions seemed dramatically uncompelling.

We learn that he has been building hotels over repurposed land, in this case over a coal mine, and to make efficient use of the space, the coal mine was also being repurposed for landfill. And so that explained the gigantic spiders: some not quite dead spider carcasses had been entrusted to a waste disposal company, which had taken those and other mutation-causing toxic waste, and buried them in the ground there. And so it turns out that the spiders aren’t aliens or the result of something alien, but are the result of human action. As so often, greed and other aspects of capitalism are singled out for criticism on Doctor Who: cutting corners can be efficient, or deadly, and sometimes both, but when the bottom line of profit is the primary concern, human lives will be sacrificed. The Doctor leads the way in confronting the situation (“I eat danger for breakfast” she says at one point) but seems to have a larger team that is more involved in figuring out what is going on, and in finding solutions, than has sometimes been typical in newer Doctor Who episodes, but is once again very much in keeping with the show’s earliest history.

Because these are normal spiders that have been transformed without wishing to, the Doctor wants to ensure that their death is humane. Robertson suggests getting a gun and shooting things “like a civilized person.” When the Doctor points out that the largest of the spiders is suffocating to death because of its transformation, Robertson shoots it anyway and calls it a mercy killing – to which the Doctor says she sees no mercy in him. His response is to say, “This is what the world needs right now. This is what’s going to get me into the White House.” Graham says about that, “God help us all.” That mention of God is the only explicit religious reference in the show, unless one includes the Islamic art in Yaz’s apartment (in British English, flat).

But on a subtler level, there is more that connects with religious and spiritual themes. The moral issues related to treatment of animals, humaneness, and business dealings as they impact both humans and animals all connect at least indirectly, as does the impact of travel. Towards the end of the episode, Graham mentions that his apartment is “full of Grace,” his wife, who he keeps imagining is there with him. Being with the Doctor helps Graham with his grief. He isn’t trying to forget – he has spoken about Grace constantly over the course of the recent episodes. He just doesn’t want to sit around doing nothing except missing her. Travel can help with that. So too can adventure, and even more so, working to help others. The Doctor’s creation of a community that does mundane things like eat and look for a parcel delivered to the wrong address, but which springs into action when it recognizes that something is going on that is harming others (even if not yet themselves directly) is a model that deserves discussion in any sort of religious, spiritual, and/or humanist context. For all the sense I had that the episode was based on a rather weakly contrived excuse for a bit of action and suspense, its vision of neighbors who don’t just turn away from others in distress, who check on an individual who hasn’t shown up at work, who challenge the unjust dismissal of an employee, who do not simply accept immoral business practices – that part is as inspiring and relevant as ever.

What did you think of “Arachnids in the UK”?