I really like this thought from the late Kim Fabricius:

Information is power. Alas, so too is misinformation.

It’s one of the things that I focused on when I taught a Speaking Across the Curriculum course at Butler University on religious rhetoric and communication, and it is something that I continue to focus on in many other contexts. The truth can be conveyed in ways that are uncompelling, and falsehood can be presented in ways that are persuasive. And so how to we do our best to render truth effective, and at the same time to combat the weaponization of falsehood? Will our era come to be known as the “Age of the Charlatan”?

Sheila Kennedy also shared thoughts on information and education, including the following:

When an “education” is limited to the transmission of technocratic skills–when we are teaching students how to derive the one correct answer to that math problem or the one correct way to program that computer–there is a very real danger that we are creating a culture in which every issue has a “right” answer and a “wrong” answer.

The humanities teach us to appreciate the complexities of human cognition, emotion and interaction. They require us to wrestle with ethical and moral questions in thorny and confounding context, and challenge us to see different perspectives and appreciate new insights.They deepen our humanity, our capacity for critical analysis, and our humility.

You can be well-trained without ever studying the humanities, but you can’t be well-educated–and we desperately need a well-educated citizenry.

Healthy student cultures at colleges and universities are generous, even as they are critical; they are open to inquiry and compromise even though they sometimes erupt into loud demands for tangible change. I don’t see only coddled snowflakes or ironic hipsters dominating these cultures. Instead, I find many studious undergrads taking time to work with refugees around the world or making room in their schedules to tutor poor children in local elementary schools. I find athletic teams raising money for cancer research, and activists volunteering their time to tutor incarcerated men and women. At campuses across the country, students are working to reduce suffering and to create opportunity.

In this time of rampant cynicism and flamboyant government corruption, students across the country are refusing to retreat from the public sphere. They refuse the dismissal of norms for telling the truth or the labeling of anything one doesn’t like as “fake.” They refuse stifling limitations on speech and action by creatively responding to changing community norms. They refuse the caricature of political correctness by listening carefully to those with whom they disagree, prepared to broaden their thinking rather than merely reinforcing their pre-conceived notions.

There is a good case to be made, today more than ever, that it is both a bad idea and badly off target to pit the humanities and the sciences against one another. 3QuarksDaily had a long piece with many quotes related to science and the humanities.

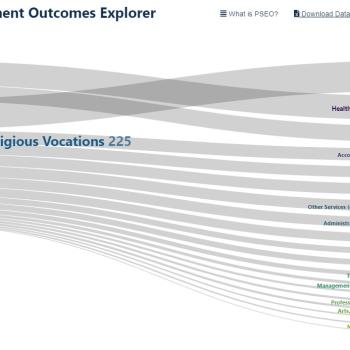

Earlier, Forbes highlighted the underemployment of business majors, emphasizing that this isn’t a phenomenon that is either unique to or even predominates in the humanities.

The Council for Foreign Relations highlighted the importance of religious literacy. Matthew Milliner did something similar, emphasizing how much of “secular” London won’t make sense without an education about religion.

Here is a toolkit making the case for the value of the humanities.

Of related interest, see Mark Grabe’s thoughts on information as educational resource, as well as the following:

OPINION: Embracing the uncertain, scary future — with a liberal arts degree

Reviving Higher Education: What I Learned by Building a University