I decided to break what had been one very long post about two mythicists into two shorter ones (although I will be the first to admit that neither is particularly short, which gives you a sense of why I thought it best to split them). The first was yesterday’s about Richard Carrier.

Today’s takes its point of departure from discussions around another mythicist, Earl Doherty. Jonathan Bernier pointed out (in a post which he subsequently deleted, but which Neil Godfrey nevertheless chose to comment on at length) that mythicists are really engaged in Christology, offering a reinterpretation of early Christian sources in a manner that is theological rather than historical. And so that is much more readily viewed as a work of reform rather than an attack, in the same sense that Luther attacked various authorities and practices, but in the interest of re-envisaging and changing.

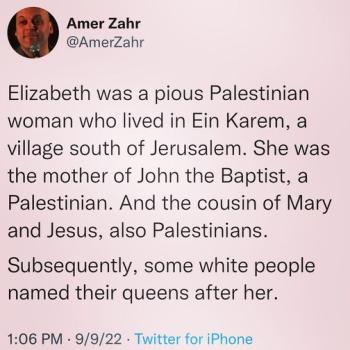

Matthew Green made a similar point in a comment on the blog a while back, suggesting that, while mythicism is at odds with what most Christians think, to the extent that many Christians are open to revising their views in light of evidence, if mythicism did turn out to be true, all that would likely happen would be a shift to focusing on learning what the celestial Jesus rather than the historical one taught. Indeed, for many Christians Jesus is a celestial figure who still speaks to them in the present day. For atheists to try to use mythicism as though it were an argument against Christianity makes no sense.

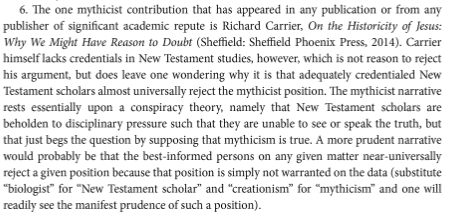

Since Jonathan Bernier’s blog post disappeared, and yet his points are always interesting and insightful, let me share a couple of great quotes from his book The Quest for the Historical Jesus after the Demise of Authenticity: Toward a Critical Realist Philosophy of History in Jesus Studies. This first one is from p.57 n.6:

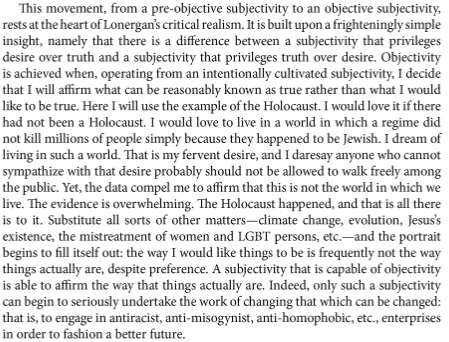

This quote from p.160 also encapsulates his point in the book as a whole, as well as in relation to mythicism:

I should also perhaps mention what an individual that I recently had to ban here sent me by email. It wasn’t an apology for his behavior, but just more of the same (although nothing as bad as what he has aimed at Larry Hurtado on his blog). His email including the following:

As to your response to Carrier, you said,

“If so, then what would it indicate if Paul singled out James as ‘the brother of the Lord’ in a letter in which he also mentions other Christians?”

Which he answers in his book: Paul did that to distinguish James in 1:19 from James the apostle. Alternately, if we assume that James the apostle was the “James, brother of the Lord” mentioned in 1:19, then a biological interpretation is falsified by the fact that Luke-Acts knows of no biological brother James who held an active role in the church.

This is typical of mythicists – being satisfied with any counterclaim without paying attention to or even giving much thought to the details. In this example, for instance, isn’t it obvious to everyone else, and not only to me, that if “brother of the Lord” means “Christian” then it is no more useful as a way of contrasting one Christian James from another who happens to be an apostle, than it is useful as a way of distinguishing between the James and Peter mentioned in Galatians?

See also the chain of bait-and-switch reasoning recently at Vridar on the same topic, with no attention to details, dates, or even references to or citations of primary sources where those would be crucial.

Jonathan Bernier also wrote a response to Joseph Atwill’s nonsense making an appearance in the news once again a while back. So too did Eldad Keynan.

See also Simon Joseph’s recent post about the crucifixion as historical bedrock and as icon.

Craig Evans’ debate with Richard Carrier from last year will likely also be of interest, the video of which is online.

Also relevant is Larry Hurtado’s discussion of being a Christian and a scholar:

Despite what some have claimed, Amazon’s Echo is not a mythicist.

Finally, mythicists are among those who are prone to misuse the term “refuted,” and thus could benefit from the linked article.