I shared many of my thoughts about the Ehrman-Price debate verbally in the conversation afterwards. But there are more points that I jotted down during the debate and/or thought of afterwards, and so I’ll share them here. Hopefully a video of the debate will eventually become publicly available online at some point.

First, I really do think that Ehrman made some of the key points with particularly impressive precision and succinctness. The point about it not being plausible that “brother” means “fellow Christian” in Galatians when referring to “James the Lord’s brother,” since he is contrasted with Peter, a Christian. The unlikelihood that the early Christians, if they invented a Davidic messiah from scratch, would invent that he was crucified.

One of his opening points – that a figure being conformed to an ideal type has no bearing on their historicity, since we see it happen time and time again to historical figures – is also crucial, and has some interesting aspects that are worth highlighting. First, one can think of other examples. Princess Diana was conformed to the “ordinary girl marries handsome prince” type even though she didn’t fit it, and in fact had more English noble ancestry than Prince Charles. Second, conforming individuals and stories about them to familiar patterns was an aid to memory, and so even though it distorted information in the process, it is not simply bad news to the historian. It is better for information to be preserved through such transformation than for it to be lost.

Although Ehrman’s point about having multiple independent sources was made in a way that reflects the consensus about the Synoptic Problem, it doesn’t depend on it inherently. If Matthew used Mark and Luke used Matthew, and John used any or all of them, we still have independent sources. Among our extant literary sources, Mark and Paul would represent independent witnesses. But because we have good reason to conclude that Matthew did not simply invent all of the teaching of Jesus he adds to Mark’s account from scratch, we would still have a third witness in the form of that oral tradition. Be that as it may, as was highlighted during the debate as well as afterwards, there is material that fits well the religious, geographical, and linguistic context of Jesus. If certain authors show a lack of direct awareness of the time of Jesus, pre-70 religious concerns, and the language he spoke, then that is all the more reason to view details that are precisely accurate – for instance, accurately recording the distinctive way Galileans pronounced certain words – as evidence that the author has access to earlier sources.

Many of the questioners at the end asked “how do we know?” and seemed to think that a lack of absolute certainty is a reason for simply believing nothing, or anything. But that is a standard denialist tactic, one that attracts only lazy thinkers. For everyone else, the hard work of analysis of evidence, and the probabilistic conclusions that result, are or should be the basis for our views of the past.

I was as disappointed as Ehrman that Price’s notion of what it meant to say that Jesus was an ordinary individual reflected not the perspective of modern historians, but the outlook of liberal Protestant clergy from more than a century ago. When Price made reference to Kenneth Copeland and Joseph Smith, however poor the analogy in certain respects, such individuals do illustrate how people who fail to impress those outside their circle of followers nevertheless can achieve a significant following and substantial influence. The choice is not between a Jesus who walked on water and one who strolled by the sea. The historical Jesus is a human individual of a well-documented sort that exists in the world today: the kind of charismatic individual who so impresses certain people that they believe they have encountered the divine through contact with that person and experienced miracles such as healing. There is nothing historically implausible about this at all.

Price was at his strongest when he emphasized that (contrary to Ehrman) scholars do propose that there may have been interpolations and alterations even when we do not have evidence in the extant manuscripts. What I think Ehrman should have said is not that no one ever proposes such things, but that (1) when there is no strong evidence either in the manuscript tradition or in the style and other features of the text, few are persuaded by such proposals, and (2) when a scholar consistently treats all material reflecting a view that they disagree with as later interpolation, it is appropriate to accuse them of special pleading.

It was interesting to hear Price speak appreciatively of the older view (associated with Bultmann, Reitzenstein, Schmithals, and others) that pre-Christian Gnosticism has influenced the New Testament. Ehrman was absolutely right to say that the texts we have were composed later, and that this view has gone out of fashion. Now, as someone who has been working on the Mandaeans, I do think that some aspects of these older views merit being revisited. But even if Mandaean literature preserves some very archaic traditions, there is simply no way to read them as the background to the New Testament, given how much later they came to be in the form in which we now have them, and given that the Mandaean texts themselves suggest that their movement started out in a non-Gnostic form. And so reading Gnosticism as the explanation to everything in the New Testament simply doesn’t work. (For a funny story about the “pan-Gnostic theory” see this earlier post.)

The appeal to much later texts was even more egregious when Price suggested that the story of Jesus’ baptism was borrowed from Zoroastrianism. In his book The Incredible Shrinking Son of Man where he makes that claim in more detail, he cites the Dinkard, which is from almost a millennium later than the time of Jesus.

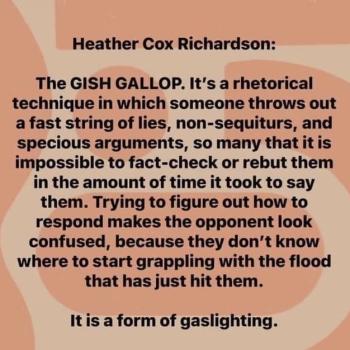

Given that Price is a Trump supporter, his dismissive statements about the academy, saying that the consensus of scholars means nothing to him, reminded me of Trump’s refusal to say that he’d abide by the outcome of the election. Scholars should by all means try to challenge the consensus. But when we can’t persuade our peers, it is not insignificant, and while by all means we may continue to believe that we are right and continue trying to make our case, we should not ever be dismissive of the collective insight of our peers in the academy.

I was also struck by Price’s attempts to characterize the community of academics as strict gatekeepers of something akin to orthodoxy, and himself as a radical and a rebel who won’t play by their rules. In fact (apart from his propensity for publishing in the Journal of Unification Studies in recent years) he has published for the most part in the same kinds of venues as others would. He may be a gadfly, and the academy needs such individuals and hopefully appreciates their importance. But he has not abandoned academia for something else, nor has it driven him from its ranks.

Those are probably enough thoughts. I’ll just conclude by saying that I appreciated the suggestion made by one of the people who asked questions at the end that celebrity or pop star might be a closer analogy than superhero comics. People think that they have seen Elvis even though he died. Perhaps because nowadays religious figures tend to be placed in that category to the exclusion of others, we forget the extent to which an ancient prophet was social critic, pop star, often a musician but at the very least a poet, and much else besides.

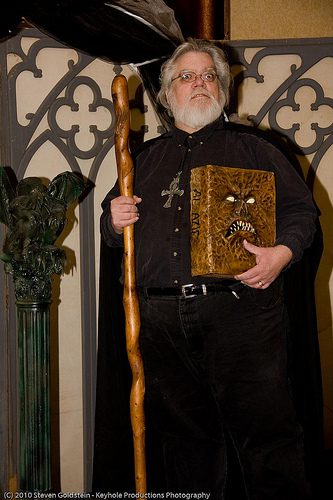

One last thing. Let me add that I appreciate the fact that Price, like myself, finds it interesting to explore other kinds of literature, including Lovecraft and comic books, and that (also like myself) it occasionally leads him to wear interesting costumes: