Ken Olson recently had a guest post on the Jesus Blog, about the Testimonium Flavianum. Olson’s chapter on this subject, “A Eusebian Reading of the Testimonium Flavianum,” is online on Academia.edu. Jim Davila and Richard Carrier also discuss this topic.

Olson’s argument is summed up as follows: “The most likely hypothesis is that Eusebius either composed the entire text or rewrote it so thoroughly that it is now impossible to recover a Josephan original” (p.100).

As Olson points out (promising that he will address these matters in future articles), Origen mentions that Josephus was not a Christian, and without some reference to Jesus rather different than the current form of the Testimonium, there would seem to be no basis for such a statement. I would also add that, while there is indeed an awkwardness to the flow in the mention of Jesus here, it is not something that is uncharacteristic of Josephus in general or this chapter in the Antiquities more specifically.

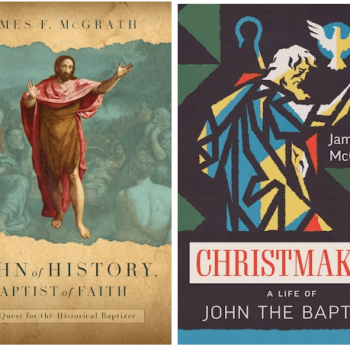

Vridar mentioned an article by Rivka Nir, which disputes the authenticity of the reference of John the Baptist by Josephus, on unpersuasive grounds. The article insists that there was a clear Jewish mainstream, rather than the diversity that most scholarship has concluded existed in this period. And Nir at times treats the immersion practiced at Qumran as fringe, other times as mainstream. And so it is hard to address the points made in the article when they seem at times to be self-contradictory.

Vridar mentioned an article by Rivka Nir, which disputes the authenticity of the reference of John the Baptist by Josephus, on unpersuasive grounds. The article insists that there was a clear Jewish mainstream, rather than the diversity that most scholarship has concluded existed in this period. And Nir at times treats the immersion practiced at Qumran as fringe, other times as mainstream. And so it is hard to address the points made in the article when they seem at times to be self-contradictory.

But in response to some of her points, it is worth considering (1) that John need not have been addressing something “mainstream,” and there may not have even been a clear mainstream in this period; and (2) the Mandaeans seem to provide precisely what Nir sees here, a wider Baptist context to which John was responding. Nir also mentions that the Pseudo-Clementine Homilies (2.23) identify John as belonging to the Hemerobaptists – i.e., those who immerse daily.

The similarities with Jewish-Christian baptism can of course be explained very well in terms of Jewish Christianity’s debt to earlier Jewish immersion rituals. Nir further writes:

The author of our passage speaks of Johannine baptism in terms paralleling

those used for expiation sacrifices in the temple cult, by means of which the person bringing the sacrifice asks God to accept it so that his sins may be forgiven.

The notion that baptism was a substitute for the Jewish sacrificial cult is manifestly Christian…

It seems on the contrary that Jewish sectarian groups, especially those that disapproved of the temple either on principle or as currently run, regularly substituted or supplemented temple sacrifice with other rituals. And so her conclusion, “the inevitable conclusion is that the description of John’s baptism, as provided in the passage under review, was not written by Josephus, but was rather interpolated or adapted by a Christian or Jewish-Christian hand” (p.62), scarcely seems to be justified by the evidence she presented.

In looking at this issue in writing this blog post, I came across a doctoral dissertation by Max Aplin, on whether Jesus was ever a disciple of John the Baptist.

It is worth noting that, while it would be nice to have additional information from Josephus about both John and Jesus, having a letter from someone who met Jesus’ brother, as well as accounts of Jesus’ life which historical criticism shows to not be entirely fictional, are enough to demonstrate that there most likely was a historical Jesus of Nazareth. The situation with John the Baptist is somewhat weaker, but still adequate. And so the question of whether John and Jesus were historical figures is independent of the authenticity of these particular passages in Josephus.

It is worth noting that, while it would be nice to have additional information from Josephus about both John and Jesus, having a letter from someone who met Jesus’ brother, as well as accounts of Jesus’ life which historical criticism shows to not be entirely fictional, are enough to demonstrate that there most likely was a historical Jesus of Nazareth. The situation with John the Baptist is somewhat weaker, but still adequate. And so the question of whether John and Jesus were historical figures is independent of the authenticity of these particular passages in Josephus.

On these topics elsewhere in the blogosphere, Ari’s Blog of Awesome recently had several posts related to mythicism, including one with video of John Barclay talking about Josephus, and another about how Robert Price promotes himself. Tom Verenna mentioned that Is This Not The Carpenter? has been released in North America. And a Hindu Patheos blogger offered thought on whether it matters whether Jesus existed.