Robert Nicastro on Teilhard de Chardin

On Monday, April 7, 2025, Robert Nicastro slew the dragon. The dragon came in the form of a dissertation defense at Villanova University. The dissertation tile? The Future as Sole Support: Metaphysics, Hyperphysics, and the Theology of Teilhard de Chardin. The faculty committee was chaired by the erudite systematic theologian, Ilia Delio, OSF. The readers of Nicastro on Teilhard included New Testament scholar Peter Spitaler along with Georgetown sockdolager John Haught. And, of course, me.

Well, you might ask: what was Nicastro’s thesis? Here is the preamble.

“Given the unique and ongoing forms of innovation and creativity that color the evolutionary process, this dissertation seeks to give serious and proper attention to the future than either science or religion by themselves has presently given that.”

Well, I certainly want to see science and religion engage one another. And I certainly give credence to a future oriented approach to divine creativity. So, what’s next? Here is the thesis proper.

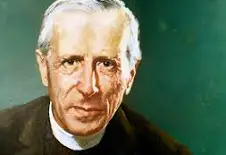

“The principal thesis of this dissertation is that such a synthesis is found in the hyperphysics of Jesuit scientist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin. In his comprehensive philosophical system, we are invited to see the cosmos as that which resonates with and gives rise to what is deepest in ourselves, which Teilhard referred to as a principle of personalization within each and every element of existence” (Nicastro 2025, 7).

To buttress this thesis, Nicastro guides us on a tour through the reductionistic and materialistic limitations of standard science as well as the unnecessarily spiritualized or disembodied inheritance of traditional Western Christianity. Nicastro applauds the innovative integration of Jesuit paleontologist and theologian, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (1881-1955).

“science cannot reach the full limits of itself either in its impetus or in its constructions without being tinged with mysticism and charged with faith” (De Chardin, The Human Phenomenon 2015, 203).349

Might we credit Teilhard with pioneering what today we call theistic evolution? Let’s take a closer look.

Who is God, Really?

A century after Teilhard began his career in scientific research, theistic evolutionist John Haught demanded that contemporary systematic theologians take evolutionary biology into account. In fact, what our context requires is an evolutionary theology. “Evolutionary theology discerns in evolution a most illuminating context for our thinking about God today” (Haught, God After Darwin 2007, 36). Haught is cashing in on the inheritance bequeathed to us by Teilhard de Chardin.

Among today’s options we find Theistic Evolution. What is it? Here is a definition supplied evolutionary biologist Martinez Hewlett and me. Theistic evolution is “a family of theological positions that see a convergence between Darwinian evolutionary theory including natural selection with the doctrine of creation” (Peters 2009, 97).

Let’s pause to think through what theism might mean within theistic evolution. Does Teilhard fit here? Evolution? Yes, definitely. Theism? Well, let’s look more closely.

Teilhard saw the existing theistic image of God as in urgent need of redefinition. A static notion of the universe has given way to a dynamic understanding of reality and therefore requires the pursuit of a new God: a God no longer simply draped with the world, but a God who is the Centre of a Universe in movement (Nicastro 2025, 176).

In contrast to the idea of divine simplicity,” obsrves Nicastro, “the realization that transcendence is found precisely in the movement of the world—physical, chemical, biological, social, scientific, artistic, religious, etc.—brings us face-to-face with the need for complexity as a new metaphysical category not only in science and philosophy but also in theology. As a result of Teilhard’s cosmic Incarnational mysticism, we are led to conclude that both the infinite and the finite are thoroughly present and entangled, each in its own proper way, and that the whole is one single flow of Spirit- matter.”

This implies, Nicastro observes, that “there is nothing outside of this whole, which includes both the infinite and the finite. All is inside the one flow—the metaphysical order of which is not simply what is but what is complex: Nature’s dynamic becoming is God’s dynamic becoming” (Nicastro 2025, 170). Nicastro denies creatio ex nihilo and substitutes an evolution of the divine in concert with the evolution of creation. “God’s creating is not one of ex nihilo from without, but rather a process of mobilizing continuous self-creativity from within” (Nicastro 2025, 187).

The result is something distinguishable from garden variety theistic evolution. Theism usually entails belief in a divinity that transcends – stands outside of – the created world. Teilhard, instead, place God exhaustively at the center of the whole of created reality. “In the course of evolution … which is our reality … God can only be defined as a centre of centres. In this complexity lies the perfection of [God’s] unity—the only final goal logically attributable to the developments of spirit-matter. Complexity of God, we have just said. Let us not be frightened by this deduction. The expression is right” (De Chardin, Human Energy 1969, 68, Teilhard’s italics).

Ilia Delio, following in the Teilhardian tradition, places God within – not beyond – the evolutionary advance. For Delio, God becomes just as the world becomes.

“By bringing together the birth of God in time and the emergence of Jesus, the Christ, Teilhard brings together the Christian hope of new creation and the evolution of complexity-consciousness. We are not outside God’s becoming. On the contrary, we are integral to the convergent and emergent process of theogenic evolution. God is being born from within. God emerges in the form of a person and has a personality marked by love. Such a position does not diminish God but “contributes something that is vitally necessary to God.” God’s self-sufficiency is paradoxically God’s dependency. God does not need matter to be God; yet, without matter God cannot be God. God is entangled with created being and created being is entangled with God … God is active and alive in a new way as new potentials for wholeness are realized. God is not utter simplicity, Teilhard suggested. God complexifies in evolution, as consciousness attains higher levels. The more consciousness is unified, the more the world converges—but only love can unify” (Delio, The Not-Yet-God: Carl Jung, Teilhard de Chardin, and the Relational Whole 2023, 207,210).

According to Delio, God is generated. God is birthed by an evolutionary midwife.

This position shared DNA with the family of theistic evolutionists, to be sure. But it might be considered a distant relative.

God does not yet exist. Really?

My own introduction to Teilhard came from two Lutheran theologians in Chicago, Joseph Sitler and Philip Hefner. They emphasized the role of the future in theological cosmology as well as the importance of evolutionary history. My next step was to become enamored with Wolfhart Pannenberg’s claim that God is the power of the future. On the one hand, this means – in a way not unlike Teilhard or Delio – that “God does not yet exist” (Pannenberg 1969, 56). On the other hand, you and I do not construct God nor does evolution create God. Rather, once the creative process of evolution and history have attained their full quiddity, then it will be clear that God has always been God. Pannenberg is an eschatological holist in much the same way Teilhard and Delio are. “To speak of the definitive unity of the world means that all events are moving ahead to meet, finally, a common future” (Pannenberg 1969, 59).

The Retroactive Power of Eschatological Being

Helpful in sorting through the issues at stake here is the distinction we find in Jürgen Moltmann and Carl Braaten between the future understood as futurum and adventus. When thought of in terms of futurum, the future is the product of growth. We plant a tulip bulb in the garden. In April, it grows into a lovely tulip blossom. All the potential originally resided in the bulb. The future blossom is the product of original potential that becomes actualized over time.

Adventus, on the other hand, points to a future that arrives with something so new that it has no precedent in the past. The future as adventus smashes into the present moment with an eschatological reality that is transformative.

Over the three and a half decades I took to write God—The World’s Future, I attempted to draw out the implications of the future as adventus (T. Peters 2015).

Not unlike Nicastro on Teilhard, I assert that God is the world’s future. More. God’s final and consummate future takes the form of the new creation, symbolized in the New Testament as the Kingdom of God. The gospel message, then, is that we have grounds for hoping in the transformation of a world gone astray and that through faith in Christ the power of the future new creation and the justice of God’s future rule become part and parcel of our life today. “So if any one is in Christ, there is a new creation: everything old has passed away; see, everything has become new. . . . For our sake he made him to be sin who knew no sin, so that in him we might become the righteousness of God [δικαισύνη Θεоû]” (2 Cor. 5:17, 21; see Rom. 6:1-11).

Or, to say it another way, the new creation is God’s creation. We are not yet created. The power of God’s future is right now in the process of bringing us toward that which we will be. The present moment takes its definition retroactively from its place in the new creation.

Here is the contrast. Teilhard and his disciples rely on future as futurum, as growth toward actualization of previous potentials. When I speak of God as the world’s future, I rely also on adventus, the future as radically new and, thereby, both transformative and retroactively definitive.

Conclusion

Spring for me is the time of the year when I greet both tulips and dissertations in blossom. If you follow my Patheos series, you know that Hyung-Joo Lee and Sang Pil Yun have already produced creative doctoral dissertations. (Links below)

Gotta git ‘m finished in time to graduate in May, ya know! I find this phase of teaching most rewarding. Why? Because we can harvest the ripening fruit that has been growing for years in the fertile soil of library research. Congratulations, Robert!

Just to stay up to date, you might check out a recent book edited by Robert Nicastro along with Ilia Delio and Noreen Herzfeld, Religious and Cultural Implications of Technology-Medited Relationships in a Post-Pandemic World (Delio, Herzfeld, and Nicastro 2023).

Patheos ST 2029 Robert Nicastro on Teilhard de Chardin

SR 5025 Big Bang and the Bible: Hyung-Joo Lee

ST 2028 What is Vocation? Ask Sang Pil Yun

Substack 2008 Two Scares of Superintelligence

▓

For Patheos, Ted Peters posts articles and notices in the field of Public Theology. He is a Lutheran pastor and emeritus professor at the Graduate Theological Union. His single volume systematic theology, God—The World’s Future, is now in the 3rd edition. He has also authored God as Trinity plus Sin: Radical Evil in Soul and Society as well as Sin Boldly: Justifying Faith for Fragile and Broken Souls. In 2023 he published. The Voice of Public Theology, with ATF Press. This year he has published an edited volume, Promise and Peril of AI and IA: New Technology Meets Religion, Theology, and Ethics (ATF) and along with Arvin Gouw an edited collection, The CRISPR Revolution in Science, Religion, and Ethics (Bloomsbury 2025). See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com and Patheos blog site on Public Theology.

▓

References

Bohm, David. 1975. “On the Intuitive Understanding of Nonlocality as Implied by Quantum Theory.” Foundations of Physics 5 93-109.

Braaten, Carl. 1969. The Future of God: The Revolutionary Dynamics of Hope. New York: Harper.

De Chardin, Pierre Teilhard. 1971. Christianity and Evolution. New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich.

—. 1969. Human Energy. New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich.

—. 2015. The Human Phenomenon. Brighton: Sussex Academic Press.

Delio, Ilia. 2023. The Not-Yet-God: Carl Jung, Teilhard de Chardin, and the Relational Whole. Maryknoll NY: Orbis.

Delio, Ilia; Noreen Herzfeld; and Robert Nicastro. 2023. Religious and Cultural Implications of Technology-Mediated Relationships in a Post-Pandemic World. Lanham: Lexington.

Haught, John. 2007. God After Darwin: A Theology of Evolution. London: Routledge.

—. 2015. Resting on the Future: Catholic Theology for an Unfinished Universe. London: Bloomsbury.

Moltmann, Jürgen. 1996. The Coming of God: Christian Eschatology. Minneapolis MN: Fortress Press.

Nicastro, Robert. 2025. The Future as Sole Support: Metaphysics, Hyperphysics, and the Theology of Teilhard de Chardin. Unpublished Dissertation, Villanova University.

Pannenberg, Wolfhart. 1969. Theology and the Kingdom of God. Louisville KY: Westminster John Knox.

Peters, Ted. 2015. God–The World’s Future: Systematic Theology for a New Era. 3rd. Minneapolis MN: Fortress Press.

Peters, Ted, and Martinez Hewlett. 2009. Can You Believe in God and Evolution? Nashville TN: Abingdon.

Rolston III, Holmes. 2010. Three Big Bangs: Matter-Energy-Mind. New York: Columbia University Press.

Smolin, Lee. 2014. Time Reborn: From the Crisis in Physics to the Future of the Universe . Boston: Mariner Books.