What is Comparative Theology?

In a previous post, ST 2022: Pope Francis vs Jesus as the Only Way?, I faulted the turbid supra-confessional universalists – otherwise known as religious pluralists — for disrespecting confessional religious traditions. The disrespect comes in the form of superimposing a non-religious concept of “the Real” or the “noumenon” or the “God with many names” upon the tradition-specific symbols of Brahman or Allah or Yahweh or even Venus or Thor.

In that post I advocated a position dubbed “confessional universalism.” Accordingly, a Christian or Muslim or Hindu makes universal claims on the basis of a specific symbol system. The ultimacy indicated by each inherited symbol system deserves respect for what it is, namely, a claim to universal truth. Without the claim to universal truth, a religious tradition is stripped of its authenticity.

This brings me to ponder a related academic discipline: comparative theology. Might comparative theology provide a fitting method for the confessional universalist? Author of the fine systematic theology, Finding God in Our Neighbor’s Faith, Kristin Johnston Largen, would answer in the affirmative (Largen 2013).

Meet Charissa Jaeger-Sanders

On the Feast Day of St. Francis of Assisi (October 4, 2024), Charissa Jaeger-Sanders passed her special comprehensive examination with distinction. Charissa is pursuing a Ph.D. in the department of Theology and Ethics at the Graduate Theological Union (GTU) in Berkeley. Her focal field is comparative theology. Her faculty mentors included me, Robert John Russell, Francis X. Clooney, and her chair, Rita D. Sherma.

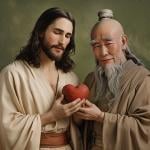

Here’s what is important for our discussion in this post: Charissa is a confessional Methodist pastor who studies Hinduism. She is not a confessional Hindu. Nor is she a supra-confessional universalist like the famed John Hick. Rather, Charissa believes her study of the goddess tradition – Devī Māhātmya – provides one source for her pursuit of Christian theology.

What are her theological sources? The Wesleyan Quadrilateral, of course, which designates Scripture, Tradition, Reason, and Experience. So, for Charissa, the goddess tradition within Hinduism provides a source for better understanding what it means to be a Christian.

What about Meta-Confessional Comparative Theology?

What is important about Charissa’s method, I repeat, is this: she takes a confessional Methodist stand while crossing over to understand from within how a Hindu disciple within the Śākti goddess tradition thinks and feels.

Might it be advantageous to abandon one’s confessional stand to engage in a meta-confessional theology which, according to Catherine Cornille, “uses the teachings of different religious traditions to pursue a more encompassing or universal truth” (Cornille 2020, 11). Not exactly. There is a problem here. Note what Cornille presupposes. She presupposes that truth is quantitative. That is, the more traditions one studies the more encompassing and universal are the truths one assembles. Is this sound?

I doubt that it works this way. Truth, I suggest, is found in the depth of meaning when qualitatively examined. It is not necessarily found by subordinating one’s own confession to seek truth in someone else’s confession. Nor is universality found this way. Universal truth is more likely found through depth analysis of rich religious symbols that are ready-to-hand.

According to Harvard’s Francis Xavier Clooney, genuine comparative theology is “mutually enriching.” This is due to the deep learning component when we cross “religious borders.” The comparative theologian seeks “to learn deeply across such borders” (Clooney 2010, 5). Deep learning requires deep reflection, not simply learning the history and thought of a different tradition. “If we are trying to make sense of our situation amidst diversity and likewise keep our faith, some version of theological reflection is required” (Clooney 2010, 3). Crossing over to engagement with the other prompts reflection upon returning home. Depth, meaning, and universality are found in reflection. Not merely in surveying a variety of religions or spiritual traditions.

Of particular interest to the comparative theologian is transformative truth when and where it can be found. “Transformative truth is available in a variety of traditions,” avers John J. Thatamanil (Thatamanil 2020, 64). Transformative truth will certainly draw the attention of the comparative theologian.

Boundary Issues

On one occasion a few decades ago, my University of Munich colleague Michael von Brück and I visited the sainted Mother Krishnabai (1903-1989) at Ananda Ashram in India. There I took the opportunity to meditate in a temple dedicated to Śiva. Sitting quietly, I could hear the chants of the Shaivite monks (including om namo śivāya). I attempted to join the chant, copying the words I could pronounce. I was actually worshipping Śiva.

After a time, I ceased active speaking and returned to passive listening. I did not want the worship of Śiva to enter my soul. I am a person who worships God in the name of Jesus Christ. Not Śiva.

At that moment I wished to understand Shaivism as empathetically as I could. But I did not want to commit idolatry. This is what confessionalism requires, I think.

Francis Clooney believes a boundary exists between religious symbol systems. Those boundaries admonish us to respect each other and to respect ourselves as well.

Conclusion

Here I have argued that comparative theology is a fit method for those who hold the confessional universalist understanding of their own religious tradition.

Perhaps more importantly, I congratulate Charissa Jaeger-Sanders on her victory. Hooray!

ST 2025 What is Comparative Theology?

ST 2023 Pope Francis vs Jesus as the Only Way, Part 1

ST 2024 Pope Francis vs Jesus as the Only Way, Part 2

ST 2025 What is Comparative Theology?

2023 Parliament of the World’s Religions: Ultimate Unity

▓

For Patheos, Ted Peters posts articles and notices in the field of Public Theology. He is a Lutheran pastor and emeritus professor at the Graduate Theological Union. He co-edits the journal, Theology and Science, with Robert John Russell on behalf of the Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences, in Berkeley, California, USA. His single volume systematic theology, God—The World’s Future, is now in the 3rd edition. He has also authored God as Trinity plus Sin: Radical Evil in Soul and Society as well as Sin Boldly: Justifying Faith for Fragile and Broken Souls. See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com.

▓

References

Clooney, Francis. 2010. Comparative Theology: Deep Learning Across Religious Borders. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell.

Cornille, Catherine. 2020. Meaning and Method in Comparative Theology. Hoboken NJ: Wiley Blackwell.

Largen, Kristin Johnston. 2013. Finding God Among Our Neigbbors: An Interfaith Systematic Theology. Minneapolis MN: Fortress Press.

Peters, Ted. 2015. God–The World’s Future: Systematic Theology for a New Era. 3rd. Minneapolis MN: Fortress Press.

Thatamanil, John. 2020. Circling the Elephant: A Comparative Theology of Religious Diversity. New York: Fordham University Press.