Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith

When on July 1, 2023 Pope Francis appointed Archbishop Victor Manuel “Tucho” Fernández to head the Vatican’s Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith, His Holiness said two things I’d like to ponder aloud. First, the pontiff addressed his Argentinian friend: “The dicastery that you will preside over in other epochs came to use immoral methods.” Second, the pontiff described Archbishop Fernández’s role as one of “promoting theological knowledge” rather than “chas[ing] after possible doctrinal errors.”

Quite earnestly, I endorese promoting theological knowledge within the wider culture for the sake of the common good.

What were those ”immoral methods” of the Inquisition?

As you may know, what today we call the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith was recently known as the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. In previous centuries it was called the Inquisition, or Supreme Sacred Congregation of the Roman and Universal Inquisition from 1542 to 1908.

What was the Inquisition again?

From the Latin inquirere, meaning “to look to”, the Inquisition was an ecclesiastical institution for combating or suppressing heresy. Heresy trials, imprisonment, torture, and execution became the Inquisition’s methods for suppressing heresy.

In the Middle Ages the Vatican took aim at heretical targets such as Catharism, the Knights Templar, Judaism [1], and Islam. In the sixteenth century, Protestants found themselves in the Inquisition’s cross hairs.

How many Lutherans were tried for heresy and died at the hands of the inquisitors during the Spanish Inquisition? Out of perhaps 150,000 persons tried and 5000 executed in Spain and the Americas over nearly three centuries, only 120 Lutherans were put to death. The executions took place in Seville and Valladolid between 1558 and 1562. Now, of course, as a Lutheran I’ve forgotten all about this. I don’t need to mention it nor bring it up. Sigh.

Maybe Pope Francis is asking his new dicastery director to avoid such “immoral methods” to eliminate Lutheran and other heresies. Whew. I can sleep more soundly tonight.

Promoting Theological Knowledge by the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith

The term, dicastery in Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith, comes from δικαστής, ‘judge, juror’. This decastery’s mission is “to promote and safeguard the doctrine on faith and morals in the whole Catholic world.” Traditionally this means “reproving” errors, heterodoxy, and heresy. But, Pope Francis has a different emphasis, namely, promoting theological knowledge.

I heartily embrace the pontiff’s positive emphasis on promoting theological knowledge. Distinguishing between orthodoxy and heresy is part and parcel of a systematic theologian’s everyday duties, to be sure. But, employing the distinction between orthodoxy and heresy as a criterion to justify putting a heretic to death does not exemplify the spirit of Jesus.

Perhaps the new dean of the Jesuit School of Theology of Santa Clara University, Agbonkhianmeghe E. Orobator, S.J., comes closer to the spirit of Jesus.

“I define theology as faith seeking understanding, love, and hope” (Orobator, 2018, p. 5).[2]

Jesus and the Systematic Theologian

Jesus was a teacher. But his teachings were cryptic, sibylline, and enigmatic. The metaphorical twists in Jesus’ aphorisms and parables were intended to shock our psyche into seeing transcendent truth hidden beneath what is very ordinary.

Today’s systematic theologian picks up where Jesus left off.[3] The task of pointing to the transcendent within the framework of ordinary human experience remains, to be sure. Since Immanuel Kant defined the Enlightenment two and a half centuries ago, however, we are no longer allowed to make literal descriptions of the furniture of heaven. All theological discourse becomes a construction based upon this-worldly experience.

So, the theologian constructs speech about the other-worldly through this-worldly terms.[4] But our speech about the other-worldly returns to shed new light on what is this-worldly too.

The theologian’s agenda is to provide knowledge that relates all things in heaven and earth to the one God of grace. At least this is what St. Thomas Aquinas thought.

“But in sacred science all things are treated of under the aspect of God, either because they are God Himself, or because they are ordered to God (sub ratione Dei) as their beginning and end” (Aquinas, 1485, p. I:1:Q.7).

I think Thomas was right.

Remind me: what is theology again?

“Theology is logos on theos,” Roman Catholic fundamental theologian David Tracy tells us (Tracy, The Analogical Imagination, 1981, p. 51). That is, theology is reasoning about God.

I doubt if the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith will ask me how to reason about God. Yet, if I would be consulted, what follows is the nub of my answer with regard to one kind of theology, namely, systematic theology. Oh, yes, we need practical theology, pastoral theology, philosophical theology, fundamental theology, historical theology, and liberative identity theologies such as feminist theology, queer theology, and such. But it’s systematic theology specifically that is tasked with the construction of a vision of God’s relation to our world that is applicable, comprehensive, logical, and coherent (Peters, 2015, p. Chapter 2). That’s a big job.

-

Systematic theology must be applicable.

By applicable I mean that there are some instances of actual contemporary experience to which theology applies. This is the bite, the point where theology digs into real life. Theology is not simply the telling of stories about other people in other times and places. There must be at least one or more present personal experiences for which theology gives the decisive—the most existentially meaningful—explanation.

There are two experiences to which applicability applies. The first is the experience of the NT disciples and apostles with the incarnate Son of God. The second is your and my everyday experience and how we reflect on it. Do these two interpret one another?

Applicability obtains for common human experience, to be sure. But it obtains also for specifically contextualized experience. The context of oppression within which loss of dignity leads the oppressed to cry out for liberation provides the bite, the point of connection between the biblical Jesus and the follower of Jesus. American Black Theologian, the late James Cone, invokes contextualized applicability.

“The finality of Jesus lies in the totality of his existence in complete freedom as the Oppressed One, who reveals thorugh his death and resurrection that God himself is present in all dimensions of human liberation” (Cone, 1970, 210).

-

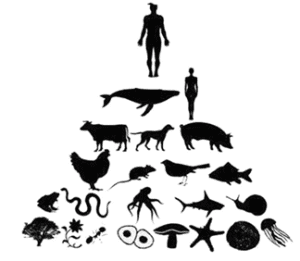

Systematic theology must be comprehensive.

By comprehensive I mean that there are no significant experienced realities that in principle are not interpretable and explainable according to the theological scheme. Because of the finite limitations of every thinker, it is impossible and unnecessary to explain every individual aspect of reality. Nevertheless, the texture of the proposed system should be porous to admit new experience with honest and meaningful incorporation.

Lutheran Philip Hefner reiterates what St. Thomas has already said about comprehensiveness.

“The essence of theology is the task of relating everything in the world to God” (Hefner 2022, 62).

Comprehensiveness inspires the church’s mission to minister to the entire creation. That’s the vision of the World Council of Churches.

“The mission of the Church is to prepare the banquet and to invite all people to the feast of life. The feast is a celebration of creation and fruitfulness overflowing from the love of God, the source of life in abundance. It is a sign of the liberation and reconciliation of the whole creation which is the goal of mission.”

Comprehensiveness is perhaps the most severe challenge confronting theology in our pluralistic era. In the pluralistic setting of contemporary life, we are well aware of competing symbol systems, many claiming to give expression to an experience with ultimate reality. One must ask critically whether behind this there are in fact different experiences. Does there exist a conflict of experiences or just a conflict of symbolizations of a common experience?

This places the systematic theologian in a dilemma. On the one hand, the theologian recognizes that we humans thirst and desire for truth. We naturally press toward an understanding of a single whole of reality. On the other hand, the theologian must begin reflection with the given, which is a collection of primary symbolizations of human experience. And these symbolizations often conflict with one another. This makes the theological task infinitely more difficult. But intellectual honesty forbids changing the criterion simply because of the difficulty in meeting it.

-

Systematic theology must be logical.

By logical I mean that theology should seek to be consistent, to avoid self-contradiction. As philosopher Alfred North Whitehead would say, “The term ‘logical’ has its ordinary meaning, including logical consistency, or lack of contradiction.” (Whitehead, 1929, 1978, 3).

If reality presents itself in experience as mysterious or as paradoxical, then this mystery or paradox should be reflected by an appropriate timidity in the system. Logic does not demand that all the bumps and wrinkles be ironed out. But it does require that what is argued avoid fallacious reasoning and that it draws only warranted conclusions. It further requires that what is asserted in one place not contradict and thereby nullify what is said elsewhere.

-

Systematic theology must be coherent.

If reality is itself relational and connected, so should theology be relational and connected. Fordham’s Elizabeth Johnson puts it this way: “”As [the Big Bang] story of the universe makes clear, everything is connected with everything else; nothing is isolated” (Johnson, 2015, p. 54).

Brazillian ecofeminist theologian Ivone Gebara not only affirms the interconnectedness of life, but she emphasizes it’s a nonhierarchical interconnectedness. It’s time to emphasize relationality minus anthropocentrism and androcentrism.

The term coherent reflects in the theologian’s mind this relationality, connectedness, unity. Coherence refers to the intrasystematic criterion that various principles within the system complement one another. Cambridge University theologian Sarah Coakley reminds us that systematic theology “is an integrated presentation of Christian truth…wherever one chooses to start has implications for the whole, and the parts must fit together” (Coakley, 2009, p. 3).

Critique of Coherence by Constructive Theology

To cohere, the various doctrinal loci need to presuppose one another and to imply one another. One should be able to enter the system through any doctrinal door and be ushered gracefully throughout the entire conceptual house. A more coherent system is more adequate than an incoherent collection.

The principle of coherence has come under fire by those calling themselves ‘constructive theologians‘. Why? Because, when the systematic theologian attempts to develop a coherent theory running through the various doctrinal loci, the system may steam roll over nuance, flattening out a plurality of experiences and perspectives.

The principle of coherence has come under fire by those calling themselves ‘constructive theologians‘. Why? Because, when the systematic theologian attempts to develop a coherent theory running through the various doctrinal loci, the system may steam roll over nuance, flattening out a plurality of experiences and perspectives.

So, there is risk in pursuing coherence. The risk is that certain positions and perspectives may get forced into a presupposed structure. This forcing may distort. Heeding such a risk alerts the systematic theologian to be cautious, watching for natural coherence rather than distorting perspectives just to make them fit the doctrinal system.

The result is that self-defined constructive theologians prefer a pluralistic approach. Accordingly, perspectives of previously marginalized groups–postcolonial studies along with political, feminist, mujerista, queer, and black theology–are collected and placed side by side. No attempt is made to systematize. Coherence is eschewed in order to guard against intellectual hegemony on the part of any one systematic theologian.

Heeding this caution, it is still my opnion that we dare not eliminate the principle of coherence. Why? Because the rational mind rests only when attending to the truth. And rational truth presents itself to the mind as coherent.

Therefore, systematic theology is rational, conceptual, rigorous, and poses hypothetical–that is, systematic theology is already constructive–explanations. Even so, we dare never forget that the subject matter of theology–namely, God–remains ever mysterious.

That God remains mysterious even in revelation has been the salient theme of Jesuit sockdolager Karl Rahner, S.J.

“For what does Christianity really declare? Nothing else, after all, than that the great Mystery remains eternally a mystery, but that this mystery wishes to communicate Himself in absolute self-communication–as the infinite, incomprehensible and inexpressible Being whose name is God, as self-giving nearness–to the human soul in the midst of its experience of its own finite emptiness” (Rahner, Theological Investigations, 1961-1988, p. 5:6).

Systematizing the Mysterious

Eight centuries ago, Thomas Aquinas could describe theology as a science. Can we do this today? Yes. But we need to acknowledge some differences.

Whereas modern scientific exploration attempts to eliminate mystery; theological reflection begins with mystery and ends with mystery. Theology is built on “the inconceivable majesty of God which transcends all our concepts,” says Wolfhart Pannenberg.

“It must begin with this because the lofty mystery that we call God is always close to the speaker and to all creatures, and prior to all our concepts it encloses and sustains all being, so that it is always the supreme condition of all reflection upon it and of all the resultant conceptualization. It must also end with God’s inconceivable majesty because every statement about God, if there is in it any awareness of what is being said, points beyond itself. Between this beginning and this end comes the attempt to give a rational account of our talk about God” (Pannenberg, Systematic Theology, 3 Volumes, 1991-1998, p. 1:337).

Systematic theology is measured by its relative adequacy.

Contrary to widespread rumor, the systematic theologian is not in the business of rendering absolute or unchangeable truth. Because theology is constructive, at best the theological system can be more or less adequate, always subject to further revision.[5]

How can one know if a theological scheme is more or less adequate? If it makes more sense. How does it make more sense? It makes sense by meeting four criteria—that is, by being applicable, comprehensive, logical, and coherent.

Public Systematic Theology

Is systematic theology a way the church thinks about what it believes? Yes.

Is systematic theology an academic discipline subject to the critique of the university? Yes.

Might systematic theology have any value to the wider culture, to the general public? Yes. When this obtains, I then call it Public Systematic Theology. I’m nudged in this direction by David Tracy.

“Theology is distinctive among the disciplines for speaking to and from three distinct publics: academy, church, and the general culture” (Tracy, The Role of Theology in Public Life: Some Reflections, 1984, p. 230).

This has led to my own thrust in public systematic theology which I define thusly. [For resources in Public Systematic Theology, click here and click here.]

Public theology is conceived in the church, critically reasoned in the academy, and offered to the wider culture for the sake of the global common good.

Now, we know that the Curia has many dicasteries. But our focus is on this one, where public systematic theology has a built in entelechy to engage not only the Church but also the academy and the wider culture. Will the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith address only the Church? Or also the academy and the wider culture for the sake of the common good?

Conclusion

The Church, the academy, and the wider culture could benefit from engaging theological knowledge. I rejoice that Pope Francis is committed to quality theological thinking within the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith.

In this Patheos post I’ve offered my own criteria by which we can measure the success of systematic theology: applicability, comprehensiveness, logic, and coherence.

Let’s pray for the success of the dicastery ministry of Archbishop Victor Manuel Fernández.

ST 2006. An Adventure in Public Systematic Theology

▓

Ted Peters is a Lutheran pastor and emeritus seminary professor. He is author of Short Prayers and The Cosmic Self. His one volume systematic theology is now in its 3rd edition, God—The World’s Future (Fortress 2015). His book, God in Cosmic History, traces the rise of the Axial religions 2500 years ago. He has undertaken a thorough examination of the sin-and-grace dialectic in two works, Sin: Radical Evil in Soul and Society (Eerdmans 1994) and Sin Boldly! (Fortress 2015).

For Patheos, Ted Peters posts articles and notices in the field of Public Theology. Watch for his new work, The Voice of Public Theology (ATF 2022). See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com.

Ted Peters’ fictional series of espionage thrillers features Leona Foxx, a hybrid woman who is both a spy and a parish pastor.

▓

Notes

[1] According to the Jewish Encyclopedia…During the cruel persecutions of 1391 many thousands of Jewish families accepted baptism in order to save their lives. These converts, called “Conversos,” “Neo-Christians” (“Christaõs Novos”) or “Maranos,” preserved their love for Judaism, and secretly observed the Jewish law and Jewish customs. Many of these families by their high positions at court and by alliances with the nobility excited the envy and hatred of the fanatics, especially of the clergy….On Sept. 27, 1480, two Dominicans, Juan de San Martin and Miguel de Morillo, were appointed the first inquisitors [of the new Spanish Inquisition]…. This tribunal, the object of fear and terror for nearly 300 years, began its work; and on Feb. 6, 1481, the first auto da fé at Seville was held with a solemn procession on the Tablada. Six men and women were burned at the stake.

[2] Saint Pope John Paul II says the same thing, but in a much more complex way.“Theology is structured as an understanding of faith in the light of a twofold methodological principle: the auditus fidei and the intellectus fidei. With the first, theology makes its own the content of Revelation as this has been gradually expounded in Sacred Tradition, Sacred Scripture and the Church’s living Magisterium. With the second, theology seeks to respond through speculative enquiry to the specific demands of disciplined thought (Pope 1998, §65).

[3] Christian theology constructs a worldview based on general principles just like philosophy. Yet, the Christian begins at the point within history where a revelation has occurred. Dogmatic theology, avers Wolfhart Pannenberg, “explicates the universal meaning of the particular individual event studied by the historian, viewing this in relation to the whole of reality and thus speaking in terms of the act of God that occurred then in the history of Jesus” (Pannenberg, Basic Questions in Theology, 2 Volumes, 1970-1971, p. 1:200).[4] Theology even in its dogmatic form does not provide literal or apodictic truth. Rather, theology incorporates constructive speculation prescinding from the historical gospel of Jesus Christ. “Doctrine is a human social construction that takes into its compass particular views of reality, both divine and human” (Helmer, 2014, p. 149), says Christine Helmer at Northwestern University. This means we measure the success of theology by its relative adequacy that can change as cultural context changes.

[5] The constructive component to theology does not leave the theologian floating aimlessly in a sea of cultural relativity. There is reference. Critical Realism is my term for the theologians method. Theological method holds “together two ideas: (1) social construction…and (2)…a reality beyond itself that social constructions attempt to convey” (Helmer, 2014, p. 160).

Works Cited

Aquinas, T. (1485). Summa Theologica (https://www.newadvent.org/summa/ ed.). Paris: New Advent.

Coakley, S. (2009). Is there a future for gender in theology? Criterion, 47(1), 2-8.

Cone, James (1970). A Black Theology of Liberation. New York: Lippincott.

Helmer, C. (2014). Theology and the End of Doctrine. Louisville KY: Westminster John Knox.

Johnson, E. (2015). Jesus and the Cosmos. In e. Niels Henrik Gregersen, Incarnation: On the Scope and Depth of Christology (pp. 133-156). Minneapolis MN: Fortress.

Orobator, A. (2018). Theology Brewed in an African Pot. Maryknoll NY: Orbis.

Pannenberg, W. (1970-1971). Basic Questions in Theology, 2 Volumes. Minneapolis: Fortress.

Pannenberg, W. (1991-1998). Systematic Theology, 3 Volumes. Grand Rapids MI: Wm B Eerdmans.

Peters, T. (2015). God–The World’s Future: Systematic Theology for a New Era (3rd ed.). Minneapolis MN: Fortress Press.

Rahner, K. (1961-1988). Theological Investigations. New York: Seabury.

Rahner, K. (1978). Foundations of the Christian Faith. New York: Seabury Crossroad.

Tracy, D. (1981). The Analogical Imagination. New York: Crossroad.

Tracy, D. (1984). The Role of Theology in Public Life: Some Reflections. Word and World 4:3, 230-239.

Whitehead, A.N. (1929, 1978) Process and Reality. Critical Edition. New York: Macmillan, Free Press.