How does Jesus save?

Part Six: The Happy Exchange

ST 2106

We have just undergone an exhausting exploration into Penal Substitution Theory or PST, which is one answer to the question: how does Jesus save? The Penal Substitution Theory was a variant on St. Anselm’s Satisfaction Theory. Whereas Anselm had distinguished between satisfaction and punishment, John Calvin equated them.

Now, we ask: is PST the only atonement theory that can make systematic theology coherent? No. Or, we ask: does Penal Substitution Theory define Reformation soteriology as a whole? No, not entirely. Let’s take a closer look.

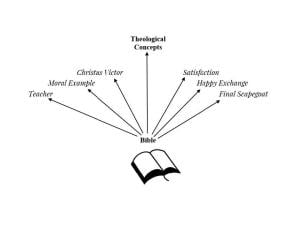

What are the alternatives in atonement theories? Here’s the list we have been working with. [See Video: Models of Atonement]

- Jesus as teacher of true knowledge

- Jesus as moral influence

- Christus Victor

- Jesus as victorious champion

- Jesus as liberator

- Jesus as Satisfaction

- Happy Exchange

- Jesus as the final scapegoat

In this post we’ll give primary attention to the Happy Exchange model, a child of the Satisfaction Theory and a sister to Penal Substitution Theory.

In this post we’ll give primary attention to the Happy Exchange model, a child of the Satisfaction Theory and a sister to Penal Substitution Theory.

5. The Happy Exchange Model

The Reformers in general developed their atonement theories in large part as extensions of Anselm’s notion of satisfaction. Here, in Luther’s Happy Exchange model, Christ suffers the penalty belonging to sinful humanity. And, in exchange, Christ bestows upon us his justice and his resurrected life.

John Calvin, recall, holds that the God of righteousness cannot love iniquity. Iniquity must be punished. Christ the mediator steps in as our substitute and takes the pain and penalties of sin unto himself. God then transfers—imputes—Christ’s righteousness to us. This, in Calvin’s view, is how Jesus Christ performs his priestly office (Calvin, Inst.II.xvi.3-6; III.xi.2). This is Calvin’s answer to our question: how does Jesus save?

Martin Luther (1483-1546) utilized all six of our atonement models at one point or another. Of particular interest to the systematic theologian in this post is the Happy Exchange (fröhliche Wechsel).

For Luther, the happy exchange relies less on satisfaction and more on the exchange of attributes (communication idiomatum). [1] In the atonement event on Calvary, the divine nature of Christ underwent suffering and death. In the Easter resurrection, the human nature of Christ took on the divine attributes of eternity and life. What is startling in the history of theology is that, according to the Happy Exchange model, the eternal divine nature suffers the vicissitudes of temporality, sin, and even death. “The pain of the cross determines the inner life of the triune God from eternity to eternity,” is the way Jürgen Moltmann puts it (Moltmann 1993, 160).

“That is the mystery which is rich in divine grace to sinners: wherein by a wonderful exchange our sins are no longer ours but Christ’s and the righteousness of Christ not Christ’s but ours. He has emptied Himself of His righteousness that He might clothe us with it and fill us with it.” (Luther, WA 1883, 5: 608)

Existentially, this can be difficult. We see death. We experience death. We don’t see resurrection. Yet, by faith we learn that an exchange is taking place. Anna Madsen, reflecting on Luther, explores the Theology of the Cross while grieving the untimely death of her husband.

“You see, that Jesus came to offer soteria, health, healing, and wholeness, suggests that the opposite is often more true: disease, decay, brokenness, and death. I am convinced that Jesus is risen from the dead. And I am convinced that in that event, he announced that death no longer has the last word—all evidence to the contrary” (Madsen 2022, 246).

Despite our feelings of despair, when it comes to application, this very exchange takes place in your and my faith. We feel the cross in our loss. Yet, God’s Word announces resurrection.

The Holy Spirit makes the resurrected Christ present in faith. The Christ who is present takes into himself your and my finitude, sin, despair, and death. We, in turn, take on Christ’s purity, faith, and resurrected life. The happy exchange takes place here and now in our faith.

The term, ‘exchange’, could be misleading. To be clear: you and I do not purchase anything. Rather, the exchange itself is a gift of divine grace. Reformation scholar Kirsi Stjerna is unequivocal on this point. “Luther’s major insight was that justification is a grace event where one is gifted freedom and forgiveness, solely by the act of Christ, who has made the reconciliation between God and human possible” (Stjerna, 2021, 65).

May I cautiously tender a further interpretation? Might we say that the Happy Exchange takes place twice? First, objectively, an exchange of divine and human attributes takes place at Golgotha in Jesus Christ. Second, subjectively, in our faith you and I exchange our human attributes with the saving attributes of the crucified and risen Christ. What do you think?

Gustaf Aulén shoots and misses

Gustaf Aulén does not include the happy exchange motif in his catalogue of atonement theories. Why not? Unfortunately, Aulén makes the mistake of saying that Reformer Martin Luther, flatly rejected the satisfaction theory and relied totally on the Christus Victor –the victorious champion–model. By throwing out satisfaction, Aulén also threw out Luther’s favorite atonement imagery, namely, that of the Happy Exchange.

The sources do not support Aulén, however. It is true that Luther employed the imagery of the victorious champion. But, certainly not to the exclusion of satisfaction or happy exchange. Luther was accustomed to using the term satisfaction and even payment and punishment when describing the work of Christ. More importantly, the notion of satisfaction underlies Luther’s doctrine of justification-by-faith (just as it does for Calvin).

The sources do not support Aulén, however. It is true that Luther employed the imagery of the victorious champion. But, certainly not to the exclusion of satisfaction or happy exchange. Luther was accustomed to using the term satisfaction and even payment and punishment when describing the work of Christ. More importantly, the notion of satisfaction underlies Luther’s doctrine of justification-by-faith (just as it does for Calvin).

Note how Luther combines Christus Victor and satisfaction motifs, including the notion of payment, in his exposition of the creed’s Second Article in the Large Catechism:

“[Jesus Christ] delivered us poor lost mortals from the jaws of hell, has redeemed us and made us free, and brought us again into the favor and grace of the Father…He suffered, died and was buried, that he might make satisfaction for me and pay what I owe, not with silver nor gold, but with his own precious blood. And all that in order to become my Lord. For he did none of these for himself, nor had he any need of it. And after that he rose again from the dead, destroyed and swallowed up death, and finally ascended into heaven and assumed the government at the Father’s right hand; so that the devil and all principalities and powers must be subject to him and lie at his feet, until finally at the last day he will part and separate us from the wicked world, from the devil, death, sin, etc.”

In Luther’s thought, the Christus Victor motif and the satisfaction motif intertwine like yarn in a Scandinavian sweater.

Luther on Satisfaction, Christus Victor, and Happy Exchange

We can see here that Luther faced the same problem Anselm confronted—that is, what is the relationship between divine forgiveness and the sufferings of the incarnate Christ? Forgiveness does not consist in a simple non-imputing of sin, as though God could have simply signed a heavenly decree henceforth absolving everybody of everything. If this were possible, then the sufferings of Jesus Christ would become unnecessary and superfluous. God’s struggle with the forces of estrangement and destruction would be a mere sham battle. What makes all this necessary, in Luther’s mind, is the need for satisfaction of divine justice—that is, the fulfillment of the divine law.

The mode of satisfaction that Christ uses on behalf of sinners is twofold: (1) he fulfills the will of God expressed in the law; and (2) he suffers punishment for sin—that is, he becomes a victim of the wrath of God. What Luther means by fulfilling the law is expressed in popular piety with the notion that Jesus was sinless. Jesus loved God and neighbor. Jesus obeyed when called to minister. Jesus did not yield to temptation. His faith was true, and he remained loyal even amid great pain and loneliness. He served God completely, even to surrendering his life.

More than this. Although he fulfilled the law, he still suffered the punishment that law ordinarily pronounces against transgressors. He was condemned to death as a law-breaker—as a blasphemer according to Jewish law and as a seditionist according to Roman law. He was innocent yet punished. It is interesting to note here that Luther goes farther than Anselm on this point. Anselm distinguished punishment from satisfaction. Luther, like Calvin, conflates the two. He assumes that it is through the punishment of Christ that satisfaction is made.

Luther thinks this through while commenting on what Paul had said in Galatians 3:13: “Christ redeemed us from the curse of the law by becoming a curse for us—for it is written, ‘Cursed is everyone who hangs on a tree.’” The curse of Deuteronomy 21:23 repeated by Paul is the punishment prescribed for someone who has committed a crime punishable by death. But Jesus Christ is innocent. How does this apply then to him? Luther’s answer: he suffers the curse for us, he receives the punishment for our capital offenses, and by doing so he satisfies the law and frees us.

God’s alien work and God’s proper work

At first glance, this may appear to stand in sharp contrast to Aulén’s Christus Victor interpretation, according to which the atonement victory consists in a triumph over the enemies of God, namely, sin, death, and the devil. When Luther is appealing to the satisfaction motif, the contest seems to be less with outright enemies of heaven than with God’s left hand. The enemy seems to be the “strange work” (opus alienum) of divine law and divine wrath. God’s “proper work” (opus proprium) is grace and forgiveness, and after all is said and done law and wrath are finally pressed into the service of salvation. The left hand ends up serving the right.

Would it be too much to hypothesize the following? For the dualism presupposed in the Christus Victor motif, sin, death, and the Devil are ontologically God’s enemies. For the monism of Luther, sin, death, and the Devil, are ontologically God’s left hand. Mmmmm?

If this obtains, demonic powers of wrath such as sin, death, and Satan are not simply and everlastingly God’s enemies. At some point, they are taken up into another dimension of divine activity and made to serve, even if unwillingly, God’s overall plan. Hence, Paul Althaus can say over against Aulén that for Luther “everything else depends on this satisfaction, including the destruction of the might and the authority of the demonic powers” (Althaus 1966, 220).

The whole mood of Luther’s understanding of Christ’s work is extremely dramatic, emphasizing the tragic depth of Emmanuelism (God with us). Jesus experiences (and here we are reminded of Irenaeus’s notion of recapitulation) all that humans experience: anxiety, fear, anger over injustice, loneliness, abandonment, God’s wrath, death, and hell. How deeply this hurt Jesus is vividly expressed in the fourth word from the cross: “‘Eli, Eli, lema sabachthani?’ that is, ‘My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?’” (Matt. 27:46). This is what Luther means by the descent into hell, by Anfechtung. So deeply does Jesus enter the human predicament that he experiences forsakenness by God, the curse of hanging from a tree.

Luther is not timid when it comes to the participation in sin by the sinless one. Christ takes possession of our sins and bears them. “Whatever sins you, and all of us have committed or may commit in the future,” Luther writes, “they are as much Christ’s own as if He Himself had committed them. In short, our sin must be Christ’s own sin, or we shall perish eternally” (Luther, LW 1955-1986, 26: 278).

Because God the Son was made sin and died, comments Patheos columnist Gene Veith, “the whole world was justified!”

Luther’s extended marriage metaphor

The value of this is that an exchange takes place. In addition to Christ’s bearing our sin, the righteousness and justice of Christ become transferred to us. Sometimes this is called the “ fröhliche Wechsel” “wonderful exchange” or “sweet exchange,” “happy exchange.” Luther describes it with a metaphor of marriage that can apply to the individual through faith or to the church as the bride of Christ:

“Faith . . . unites the soul with Christ as a bride is united with her bridegroom. By this mystery, as the Apostle teaches, Christ and the soul become one flesh (Eph. 5:31f). And if they are one flesh and there is between them a true marriage—indeed the most perfect of all marriages, since human marriages are but poor examples of this one true marriage—it follows that everything they have they hold in common, the good as well as the evil . . . Christ is full of grace, life, and salvation. The soul is full of sins, death, and damnation. Now let faith come between them and sins, death, and damnation will be Christ’s, while grace, life, and salvation will be the soul’s” (Luther, LW 1955-1986, 31: 351).

A feminist critique of Luther’s imagery

The marriage imagery is outdated. It suggests that the husband redeems the wife. Does the wife need redeeming? Perhaps friendship imagery would put both partners on an equal level, suggests St. Olaf theologian Deanna Thompson.

“I suggest a revisioning of Luther’s use of the metaphor of a fröhlicher Wechsel, or happy exchange between the bridegroom and bride, to understand atonement….In our contemporary setting…much of the power of this metaphor is muted or lost for women and men who cannot move past its sexism. The model of Christ rescuing humanity in the form of a deviant woman needs to be replaced in a cross-centered theology with a feminist sensibility. Rather than a happy exchange between Christ and the wicked harlot bride, I suggest a metaphor that communicates several key aspects of a feminist theologian of the cross’ understanding of atonement. It is the model of friendship; that God’s atoning work for us on the cross is done through Jesus’ befriending humanity.” (Thompson 2022, 103)

Whether a sixteenth century image of the perfect marriage or a twenty-first century image of a genuine friendship, the message of Luther’s happy exchange is what I elsewhere call Emmanuelism (God with us) (Peters 2015, 205-206). As God binds Godself to us, we become unbound as we are born anew into the divine freedom. This is how atonement works for Luther. It is this happy exchange combined with the mysterious unity we share with Christ through faith that underlies the doctrine of justification. If Christ is just, and if his justice is exchanged for our injustice, then we become declared just on account of Christ. It is here that we find the heart that pumps life and new life throughout everything having to do with the Christian faith. It is the gospel.

Conclusion

If the systematic theologian were a dendrologist, we might end up with the following extended metaphor: Anselm’s Satisfaction model provides a tree trunk with a fork. Calvin and Luther represent two branches. Calvin’s Penal Substitution Theory and Luther’s Happy Exchange model are both rooted in satisfaction. And both conflate satisfaction and punishment.

Luther’s branch relies much more heavily than Calvin’s on the communication of attributes (communicatio idiomatum). The physical presence of God in Christ and in our daily faith sprouts leaves one would not find on Calvin’s branch. The divine nature absorbs into itself the historical experience of physicality including suffering and death. In exchange, the divine nature cedes to the human nature healing and resurrection. The exchange takes place in the person of Christ on Calvary and then again between Christ and the person of faith here and now.

This is Martin Luther’s answer to the question: how does Jesus save? Imagine praying with Luther.

“Lord Jesus, you are my righteousness, just as I am your sin. You have taken upon yourself what is mine and have given to me what is yours. You have taken upon yourself what you were not and have given to me what I was not….” (Luther, LW 1955-1986, 48: 12-13)

▓

Ted Peters is a Lutheran pastor and emeritus seminary professor, teaching systematic theology and ethics. He is author of Short Prayers and The Cosmic Self. His one volume systematic theology is now in its 3rd edition, God—The World’s Future (Fortress 2015). His book, God in Cosmic History, traces the rise of the Axial religions 2500 years ago. He has undertaken a thorough examination of the sin-and-grace dialectic in two works, Sin: Radical Evil in Soul and Society (Eerdmans 1994) and Sin Boldly! (Fortress 2015). Watch for his forthcoming, The Voice of Christian Public Theology (ATF 2022). See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com.

Ted Peters’ fictional series of espionage thrillers features Leona Foxx, a hybrid woman who is both a spy and a parish pastor.

▓

[1] “Communicatio idiomatum as Luther explains, takes place in three ways: one, communication of attributes between the divine and human attributes in one person Jesus Christ; two, communication of properties between the two natures; and three, communication of attributes between God the Creator and God the redeemer is extended in the same manner to each human (believer) and the whole humanity” (Penumaka 2022, 125).

[1] “Communicatio idiomatum as Luther explains, takes place in three ways: one, communication of attributes between the divine and human attributes in one person Jesus Christ; two, communication of properties between the two natures; and three, communication of attributes between God the Creator and God the redeemer is extended in the same manner to each human (believer) and the whole humanity” (Penumaka 2022, 125).

Bibliography

Allen, David. 2022. “A Critique of Limited Atonement.” In Calvinism: A Biblical and Theological Critique, by eds David L Allen and Steve W Lemke, 71-128. Nashville TN: B&H Academic.

Althaus, Paul. 1966. The Theology of Martin Luther. Minneapolis MN: Fortress.

Anselm. 1966. Cur Deus Homo. LaSalle IL: Open Court.

Aulén, Gustaf. 1967. Christus Victor. New York: Macmillan.

Calvin, John. 1535. Institutes of the Christian Religion . Tr. Thomas Norton: https://www.ccel.org/ccel/calvin/institutes.toc.html.

Hultgren, Arland. 1987. Christ and His Benefits: Christology and Redemption in the New Testament. Minneapolis MN: Fortress.

Madsen, Anna, 2022. “Suffering and the Theology of the Cross.” Encounters with Luther.

Eds., Kirsi Stjerna and Brooks Shramm. Louisville KY: Westminster John Knox.

Luther, Martin. 1955-1986. LW. Luther’s Works, American Edition, 55 Volumes: St. Louis and Minneapolis: Concordia and Fortress.

—. 2016-2019. The Bondage of the Will (1525) / The Annotated Luther, 6 Volumes. Minneapolis MN: Fortress Press.

—. 1883. WA. D. Martin Luthers Werke: Kritische Gesamtaufgabe 69 volumes: Weimar: Hermann Böhlaus Nachfolger.

Moltmann, Jürgen, 1993. The Trinity and the Kingdom. Minneapolis MN: Fortress.

Penumaka, Moses. 2022. “Towards Interreligious Spiritual Hospitality: A Lutheran Perspective.” Religion and Sustainability. Eds., Rita D. Sherma and Purushottama Bilimoria. Switzerland: Springer; 115-133.

Peters, Ted. 2015. God–The World’s Future: Systematic Theology for a New Era. 3rd. Minneapolis MN: Fortress Press.

Stjerna, Kirsi. 2021. Lutheran Theology: A Grammar of Faith. Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark.

Thompson, Deanna, 2022. “Becoming a Feminist Theologian of the Cross.” Encountering Luther. Eds., Kirsi Stjerna and Brooks Shramm. Louisville KY: Westminster John Knox.