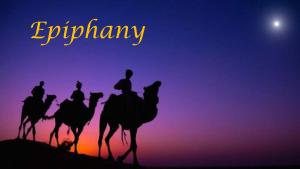

What is Epiphany? Oh, yes, the three wise men on camels show up at Jesus’ manger with gold, frankincense, and myrrh. But the significance of epiphany here is that knowledge of God’s plan of grace has now spread from Israel to Iran (Persia) and the wider world. We celebrate this event each year on January 6.

What is Epiphany? Oh, yes, the three wise men on camels show up at Jesus’ manger with gold, frankincense, and myrrh. But the significance of epiphany here is that knowledge of God’s plan of grace has now spread from Israel to Iran (Persia) and the wider world. We celebrate this event each year on January 6.

What is epiphany? Try 2 Timothy 1:10 for an answer. “It has now been revealed through the appearing [epiphany] of our Saviour Christ Jesus, who abolished death and brought life and immortality to light through the gospel.” Patheos columnist Mark Roberts alerts us. “If you were reading this verse in Greek, you’d find the word epiphaneia where we have ‘appearing’. God has made all of this plain to us through the epiphany of Christ.” Now we ask: is what God made plain through the epiphany of Christ still so plain?

In America, January 6 has become remembrance day for Donald Trump’s assault on the U.S. Capitol. Not the arrival of the three kings. What is happening?

What our global communications network needs most right now is a divine epiphany. We need an epiphany which establishes what is sacred, what is ultimate, what is central. Without a sacred, we find ourselves ducking in a crossfire of wholesome worldviews with destructive worldviews, information versus disinformation, science battling pseudoscience, cute kitties contrasted by Satanic monsters, and harmony trying to combat acrimony. Social media is social bedlam.

A Center plus a Horizon make a Worldview

There is no center. There is no sacred. There is no point of orientation. There is no horizon.

There is no center. There is no sacred. There is no point of orientation. There is no horizon.

Our forbearers lived in a cosmos with a sacred center: God’s epiphany in Jesus Christ. Or, at least in other religious traditions a corresponding sacred. It takes a center surrounded by a horizon to provide a lifeworld (Lebenswelt), a worldview. [Art by Gloria Baker Feinstein]

Today’s global plurality is hostile to the sacred Christ. And to all other centers as well. Our planetary society has been unable to orient itself around any center. Not even Planet Earth functions as a center. All is profane.

The pioneer history of religions scholar, Mircea Eliade, observed that „The completely profane world, the wholly desacralized cosmos, is a recent discovery in the history of the human spirit“ (Eliade 1957, 13). Today’s social media only makes obvious the underlying cultural pandamoniam.

What is epiphany? Is it planting a flag?

One way to create a center is to plant a flag. Armies plant flags after they conquer. A flag symbolizes that the new center will be the empire or emperor. What is sacred will be determined by bully domination, by the the totalitarian state.

The new evangelical atheists have adopted this flag planting strategy. „If ya want knowledge,“ says the general in the atheist army, „ya gotta come to me. Knowledge belongs only to science. And I say there ain’t no religious knowledge.“

Like so many among the Patheos columnists, I enjoy the toe-to-toe interactions on social media. I’m a member of one group where atheists and theists go back and forth. I’ve run into a number of ideological materialists who base their atheism on science. Here’s a recent post almost but not quite verbatim. „I only believe what is logical. Either A, or not A. Science is the only path to knowledge. All in religion is myth, fable, or lies.“

Let’s ponder this position for a moment. An epistemological flag has been planted. This flag says that science has won a total victory over all other contenders. Science, it is claimed, holds an exclusive patent on knowledge. Religion or art or poetry or history dare not infringe on this patent.

There’s a term for this ideology. It’s scientism. By adding an „…ism“ to „science,“ we get an ideology. Strident materialist Peter Atkins expresses the attitude. “Science is the only path to understanding. It would be contaminated rather than enriched by any alliance with religion” (Atkins 2006, 124).

Genuine science provides knowledge that we all celebrate, to be sure. But, science as science need not be an all-inclusive ideology with the flag of hegemony planted in religious territory. Science, yes. Scientism, no.

One of my mentors, University of Chicago’s Langdon Gilkey, believes science and theology speak two complementary languages. “My critique is not of science…The view of science that I criticize (1) sees science as the only way to know reality and so the only responsible means for defining reality for us and (2) views the results of science as providing an exhaustive account of reality or nature and hence as leaving no room for other modes of knowing such as aesthetic, intuitive, speculative, or religious modes” (Gilkey 1993, 2). Gilkey would say that belief in the patent on knowledge is not in itself scientific. It’s an act of faith. Worse. It’s an act of faith without a sacred center.

Here’s what’s relevant to this conversation on epiphany. The material world made known by scientific research is homogenous, uniform, uninterrupted by human subjective meaning. Everything is profane, so to speak. Not evil, to be sure. Just not sacred. Or, in more common parlance, it’s difficult for a materialist atheist to formulate a worldview with ultimate meaning. Before smug Christians start throwing “I tol’ ya so” darts, let’s continue considering what is at stake.

To be human today is to live informed by the homogeneous knowledge of science but still to look for the disruptive sacred to orient a robust worldview. „The manifestation of the sacred ontologically founds the world“ (Eliade 1957, 21). A Christian wants a worldview where the sacred center vibrates and emanates the grace of the true God.

God’s Epiphany

Should a religious army plant its worldview flag and demand that everyone else see it as sacred? Should Christian epistemology bully other epistemologies? Well, that just won’t work. Sacred bullying does not befit God’s grace. Nor does it respect the persons to be graced. So we must ask again: what is epiphany?

A genuine or authentic center is not subject to bully rule. The sacred cannot be forced on the human spirit. The sacred comes to us, according to Eliade. „Something sacred shows itself to us“ (Eliade 1957, 11). [Art: El Grecco]

To put this theologically, a genuine epiphany rather than a military flag belongs to God’s initiative. Not ours. The late Tübingen theologian, Christoph Schwöbel, put it this way. “God can only be known when and where God makes Godself known” (Schwobel 2018, 349).

Or, according to Kristin Johnston Largen, former editor of Dialog, A Journal of Theology. “It is God first and foremost who makes knowledge of God possible” (Largen 2013, 133).

If God does not reveal the divine self, then we simply will know nothing truthful about God. Oh, yes, we could imagine and project and blather on about what we want the transcendent to be like. But, to learn that our creating and redeeming God is gracious, that takes an epiphany.

What is epiphany? It includes both Object and Subject

Knowledge of God does not just sit in reality waiting for someone to discover it. Knowledge of God is not an item on a menu waiting for us to read it. For God to be revealed, God must reveal the Godself to somebody. Epiphany is an event that includes the revealer, what is revealed, and the one to whom revelation is revealed.

“Since there is no revelation unless there is someone who receives it as revelation,” announces Paul Tillich, “the act of reception is part of the event itself” (Tillich 1951-1963, 1:35). God, the object of revelation, is received by the subject who participates in the revelation.

The matter gets more complicated. What is revealed first about God is that God is mysterious. Scientific research routinely reduces mystery. Whereas scientific research replaces mystery with knowledge, epiphany enhances mystery. What we get from epiphany is not so much knowledge, but rather a relationship with God. Epiphany increases mystery. Is this paradoxical? You betcha.

The mystery does not disappear even in the event of revelation. “Revelation does not remove the mysteriousness,” says Lundensian theologian Gustaf Aulen (Aulen 1960, 83). God is revealed as impenetrable mystery. Yet the time and place of this revelation marks the sacred. Where and when the epiphany happened marks the center of a religious worldview.

And to make it still more complicated, a genuine epiphany from the genuine God upsets what we previously believed. “A considerable part of the effect of the Christian revelation will be a shaking up of what is apparently ‘right’ and what is apparently ‘wrong’,” observes theologian James Allison (Allison 2010, xi). Sometimes an epiphany shocks us. Shock or no shock, the epiphany centers us so that our horizon broadens and our mind integrates our experience into a meaningful lifeworld.

Conclusion

World peace is at stake. Planetary survival is at stake. Racial justice is at stake. Human flourishing is at stake. The crossword puzzle that makes up global communications is being blown about by a hurricane of disintegration. For the sake of both survival as well as sanity we desperately need a centered worldview.

In this series of Patheos column posts, I’ve repeatedly assigned to public theology the task of worldview construction. Such construction might take two forms. First, the public theologian could identify and reinforce existing commitments to ecological ethics, racial justice, economic justice, human dignity, and respect for scientific knowledge whenever and wherever possible. Let’s build on existing foundations. Let’s construct a worldview on existing positive social thrusts.

So, what if this accentuation of existing positive thrusts does not suffice? It might not. Why? Because our planetary society lacks a center. More importantly, it lacks even the impulse to find a center. There is no sacred to orient our planetary community. There is no pole of truth around which our perceptions of reality can be oriented. Nor, does there seem to be a yearning for that sacred center.

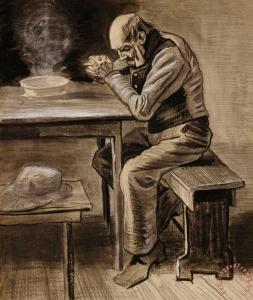

What’s a public theologian to do? My answer, secondly, is this. Pray. [Art: 1882 Vincent Van Gogh]

Yes, pray. Ask God to provide an epiphany that only God can provide. And, while we’re waiting for God to provide this epiphany, the public theologian should continue to encourage what is already healthy, protean, and beautiful. Accompanying this public encouragement, a prayer request is quite appropriate. Let’s try a short prayer on for size.

“God of our creation and redemption, provide our world with an epiphany. Assure our entire planetary society that our reality is grounded in divine grace. Amen.”

Works Cited

Allison, James. 2010. Broken Hearts and New Creations: Intimations of a Great Reversal. New York: Continuum.

Atkins, Peter. 2006. “Atheism and Science.” In The Oxford Handbook of Religion and Science, by eds., Philip Clayton and Zachary Simpson, 124-136. Oxford UK: Oxford University Press.

Aulen, Gustaf. 1960. The Faith of the Christian Church. Minneapolis MN: Fortress.

Eliade, Mircea. 1957. The Sacred and the Profane. New York: Harcourt Brace and World.

Gilkey, Langdon. 1993. Nature, Reality, and the Sacred: The Nexus of Science and Religion. Minneapolis MN: Fortress Press.

Largen, Kristin Johnston. 2013. Finding God Among Our Neighbors: An Interfaith Systematic Theology. Minneapolis MN: Fortress Press.

Schwobel, Christoph. 2018. “The Eternity of the Triune God.” Modern Theology 34:3 345-355.

Tillich, Paul. 1951-1963. Systematic Theology. 1st. 3 Volumes: Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

▓

Ted Peters is a Lutheran pastor and emeritus seminary professor. His one volume systematic theology is now in its 3rd edition, God—The World’s Future (Fortress 2015). He has undertaken a thorough examination of the sin-and-grace dialectic in two works, Sin: Radical Evil in Soul and Society (Eerdmans 1994) and Sin Boldly! (Fortress 2015). Watch for his forthcoming, The Voice of Public Christian Theology (ATF 2022

Ted Peters is a Lutheran pastor and emeritus seminary professor. His one volume systematic theology is now in its 3rd edition, God—The World’s Future (Fortress 2015). He has undertaken a thorough examination of the sin-and-grace dialectic in two works, Sin: Radical Evil in Soul and Society (Eerdmans 1994) and Sin Boldly! (Fortress 2015). Watch for his forthcoming, The Voice of Public Christian Theology (ATF 2022