From the Revised Common Lectionary this week, a reflection on Acts 11:1-18 and John 13:31-35.

A common and pervasive misunderstanding of Christianity maintains that theology never changes. (An equally common and pervasive notion, to consider at another time, is that God never changes.) This is the most basic definition of theological conservatism. By contrast, progressive Christianity understands that theology is fluid and dynamic, never static.

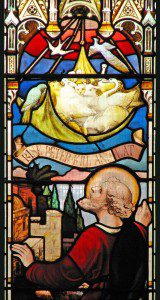

Of the biblical traditions we can use to demonstrate this reality, perhaps none is more relevant to today’s theological debates than the gradual acceptance of Gentiles into the fold of Jesus’ earliest followers. Our picture of Jesus himself is rather ambiguous when it comes to ministry among non-Jews—the mixed messages of the gospels are no doubt the result of the earliest Christian communities struggling with this issue. And while Paul becomes the most influential missionary among the Gentiles, it was Jesus’ closest disciples, Peter, who first preached the good news among the Gentiles in Caesarea and witnessed the Holy Spirit filling them in the same way as had been experienced by the Jewish followers of Jesus in Jerusalem.

While the story of Peter at Caesarea is recounted in Acts 10, in Acts 11 we find the theologically conservative Jewish Christians in Jerusalem criticizing Peter’s inclusion of non-Jews. Peter defends his actions by sharing with them the vision narrated in the previous chapter, in which God signals the radical reversal of centuries of theological divisions between the children of Israel and the rest of the world. Peter also shares that the Gentiles at Caesarea experienced God in the exact same way that they had on Pentecost. This convinces Peter’s more conservative friends and they end up praising God for this remarkable turn of events.

The parallels to today are clear. In recent memory the Bible and theology were used to claim that people of African descent were designed by God as inferior and to prevent women from serving in leadership roles in the church. Sadly, in some Christian circles these ideas persist. But most Christians have progressed beyond these mistakes of the past.

Our most public debate now is about the full inclusion of LGBTQ people in the life of the church. A handful of biblical texts—a line of thinking much less represented in the Bible than the division of Jews and non-Jews that was undone in the earliest days of Christianity—are used to maintain the exclusion of people who have experienced the Holy Spirit in the exact same way as their non-LGBTQ siblings. We are experiencing the same kind of radical shift in our theological tradition today as Peter and Jesus’ Jewish followers experienced when Gentiles were first recognized as children of God.

Among the theological and interpretive strategies used by progressives to discern the ongoing work of the Holy Spirit in the church and world is the centrality of love in the way of Jesus, exemplified this week in the new love commandment of John 13. As a hermeneutical guide, we often associate this with Augustine’s “rule of love”:

Whoever, then, thinks that he understands the Holy Scriptures, or any part of them, but puts such an interpretation upon them as does not tend to build up this twofold love of God and our neighbour, does not yet understand them as he ought. (On Christian Doctrine, 1.36.40)

I like to think of the rule of love as our theological trump card when it comes to understanding difficult passages of the Bible and theological traditions that now seem in conflict with the ongoing revelation of God’s nature and will for the world.

As you study these passages with your youth, consider these questions:

- Is the notion that theology changes unsettling or does it give you hope?

- What other things “that have always been this way” might the Holy Spirit be leading us to reconsider?

- How can the rule of love guide your reading of the Bible and study of theology?

- How can the rule of love guide your everyday living?