Venturing into Middle America to see what middle Americans find entertaining has become a right of passage for cultural critics. We intellectuals often find ourselves in states of shock, obnoxious ostentation, and occasionally, are emotionally moved by our visits to roadside tourist sites in the Flyover States. Having visited—indeed gone on a three-day pilgrimage—to see the Precious Moments Chapel in Carthage, MO, over Independence Day weekend, I was filled with tales to tell my educated friends about the religio-consumer habits of the proletariat. Only to find the first two people I called had been to the Museum of Earth History, a creationist museum in Dallas, and the Christian kitsch palace of the headquarters of the Trinity Broadcasting Network in Orange County, CA on the same weekend. My tour of a “Sistine Chapel” dedicated to figures of teardrop-eyed urchins was fascinating but hardly original.

Italian semiologist Umberto Eco beat us all to the Middle America pilgrimage in his 1986 book, Travels in Hyperreality, in which he visited Disneyland, the (now closed) Palace of Living Art, and the (now closed) Museum of Magic and Witchcraft on Fisherman’s Wharf in San Francisco. Eco labeled America as the home of the hyperreal—or as he describes it: “those instances where the American imagination demands the real thing and, to attain it, must fabricate the absolute fake” (8). It’s a lens we Americans see the world through, in which something must be “real,” but somehow better than real. It must always be recreated to have even more of the substance we like.

The Precious Moments line of figurines, dolls, greeting cards, books, videos, and home decorating items are the most popular collectables in the United States, so it seems fitting that someone would create a place where these figures lived. In the case of these sentimental expressions of Red State Christianity, the ‘real thing’ and ‘absolute fake’ is most appropriately a chapel and a memorial garden, reflecting on the ultimate “precious moment”—death.

What Precious Moments, Inc., founded by artist Sam Butcher, has done in addition to creating a hyperreal space for its figurines, is to create hyperreal children. Precious Moments children are like children, but better. They’re pastel-colored and clean, usually light-skinned and fair-haired (the American ideal of beauty). They’re always in adorable poses, with puppies and kittens, or playing dress-up as doctors or teachers. Their shoes and clothes are patched and faded to make them look like lovable ragamuffins. And they usually reflect some Bible verse or Christian virtue in the most innocent, un-self-conscious way. Although they are sometimes depicted as mothers and fathers—even as grandparents—or doing adult work or driving cars, they are always large-headed and pre-pubescent.

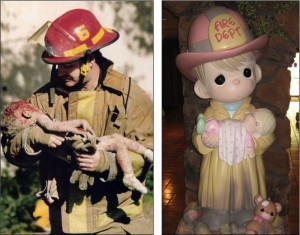

The Precious Moments complex, fittingly, begins with a gift shop, and a kind of castles-and-maidens fantasyland in which dolls dance around in clunky animatronic movements. There are also several sculptures of giant Precious Moments figures, their teardrop eyes staring blankly as you walk by. One large sculpture is a figure modeled on the famous news photo of a fireman holding a dead baby found in the rubble of the Oklahoma City bombing. The figurine of the statue was never cast or sold because of objections from parents of the young victims of the bombing.

The Oklahoma City firefighter is just one of many juxtapositions of kitsch and death on the grounds of the chapel. Butcher had seven children, but has lost two of his sons, one just last year. Much of the building itself is dedicated to Butcher’s son Philip, who died in 1990. There is mural in a room of the chapel that shows what appear to be children surrounding the bed of Philip, looking sad and confused as he is taken up into heaven. Philip himself is depicted as a blond child, being given toys upon his entry into the afterlife. It takes some real investigation to figure out that Philip was in fact 27 when he died, and some of the “children” in the mural are Philip’s own wife and children.

The chapel itself impresses the viewer with color and light; gospel hymns in contemporary instrumental style drone in the background, creating a peaceful, if not tasteful, aura. The paintings on the sides of the chapel mostly represent Bible stories or parables. The largest painted piece at the far end of the nave and is called Hallelujah Square—a Precious Moments answer to Michelangelo’s Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel. As erotic, chaotic, dynamic, and frightening as Michelangelo’s fresco is, Butcher’s “Last Judgment” is correspondingly sexless, droll, passive, and reassuring. The Heavenly Gate is really more of a turnstile, as an angel named Timmy “Welcomes” you “to your heavenly home” and promises, “No more tears.”

In other parts of the chapel, it is explained that many of the children in the Hallelujah Square are actual people Butcher knew who died – again, many of them as adults. Visitors are encouraged to leave comments in log books remembering people they have loved who have died, and can buy bricks to be placed as memorials in the plazas outside the chapel. The company has even licensed Precious Moments caskets and tombstones.

As with most stories of “artists” who create collectables, Sam Butcher’s background is more complex than the squeaky-clean mythology the company creates around him. According to research around the ‘Net, Butcher is divorced, spends most of his time in the Philippines, and has struggled with alcoholism and bipolar disorder. Now in his mid-70’s, he has mostly had to discontinue his artwork because of a stroke.

The chapel itself and the grounds around it were well-kept, but there seems to be some faded glory in the gift shop section. I expected the shop to be stuffed with collectables, and the company has recently launched some successful licensing deals with Disney, Major League Baseball, and Raggedy Ann characters and logos. But parts of the shop were also selling purses and earrings—a strange addition to what seemed to be an under-stocked store.

The company fell on hard times a few years ago, when the bottom dropped out of the collectables market and the company that had made the figurines for 25 years, Enesco, went bankrupt. Precious Moments suddenly had to take on making and shipping the figurines themselves. Around that time, other features of the chapel theme park closed, including the Precious Moments Wedding Island, (yes, you could get married in an official Precious Moments ceremony), the Precious Moments RV park, and a Las Vegas style fountain and light show.

As an observer, I found myself unsure how to react to the expressions of grief in several of the spaces of the chapel. I find it strange that an artist, or his collectors, could be seemingly incapable of processing grief except through these tear-eyed figurines. And what is the obsession with children as heavenly creatures? Children are wonderful and offer great spiritual and human insight. Obviously Jesus recognized this, which is why children hold a special place in the Gospels. But do we really become less-than-heavenly beings when we go through puberty? And must we regress to pre-adolescence before we are able to be “welcomed to our heavenly home?”

What seemed obvious to me was that certain manifestations of the brand were completely inappropriate. There is nothing “precious” about a terrorist strike and mass murder. The fact that Butcher would feel moved to create a Precious Moments Oklahoma City firefighter suggests all the poor artistic instincts that purveyors of kitsch have been accused of for at least a century.

But I also couldn’t ignore the observation that for many people, a visit to the chapel was a genuinely cathartic act. This, along with experiences of the deaths of my own relatives, has convinced me that for all its artistic shortcomings, kitsch is sometimes the spiritual glue that holds us together. Death is difficult and confusing; it leaves us incapable of processing greater abstract truths about the universe. When coping with death, most of us seek comfort in familiar food, music, or art. Kitsch, an art form that is based purely on emotion, sentiment, and sensation, is tailor-made for these moments. This why you’ll frequently find sign-in books by Thomas Kinkade at a funeral home viewing, or Precious Moments collectables commemorating the death of a loved one.

As I left the chapel, I couldn’t help but enjoy the irony of seeing a mom with her two small kids, shouting at one while the other pulled up American flags from the grounds around the chapel. Beyond expressions of grief, maybe that’s part of the appeal of the hyperreal children created by Precious Moments. Parents can gaze on these perfect children, forever frozen in poses of innocent insight and unconditional love, while their real children destroy the house, ride the dog like a pony, and slap-fight over Legos and action figures. In this case, kitsch and the hyperreal become vehicles for momentary escape. And who doesn’t need that every once in a while?