In 1958, Malcolm Boyd, an Episcopal priest and former Hollywood writer, soon to be known as author of the bestselling prayer book Are You Running with Me, Jesus? offered a contemporary assessment of 1950’s biblical epics. In Christ and Celebrity Gods: the Church in Mass Culture, he called the films “orgiastic, lengthy, overwhelming spectacles that have as little relation to ‘religion’ as orange juice stands have to a cocktail bar.” He went on to lament the genre’s “wildly imaginative excursions of script, the lavish bad taste of garish sets, [and] objectionable treatments of sexuality as against Puritan taboos identified with the will of God.” Specifically criticizing the rapturous approval of clergy to DeMille’s The Ten Commandments (1956), Boyd said that attempting to point out the many negatives of the film had “become, almost, a kind of McCarthyism in terms of strictly ecclesiastical circles. Honest expression was lacking. One felt an absurd, but threatening, kind of fear of speaking out against the film.”

Those few clergy like Boyd who objected to the Commandments were spitting into a hurricane of Paramount-produced publicity. Prior to his release of the film, DeMille had lined up endorsements from Eugene Carson Blake, president of the National Council of Churches of Christ; legendary Baptist minister W.A. Criswell; Abraham Feldman, president of the Synagogue Council of America; Bishop Gerald Kennedy, the most prominent Methodist of the era; Raymond Lindquist, president of the National Board of Missions of the Presbyterian Church; David O. McKay, president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints; Ralph W. Sockman of Christ Church Methodist in New York, preacher of National Radio Pulpit on NBC radio from 1928 to 1962; and Cardinal Francis Spellman of New York City. Another way to describe this assemblage, using the language of the time, was that DeMille had brought together the most powerful “churchmen” of the era to endorse his film. In the face of these figures, a negative review of the film could quite literally be understood as heresy.

Boyd’s evocation of McCarthyism was also not far from the historical reality of the times. Pulsing through the wave of adulation surrounding the Commandments was an understanding that America was under serious ideological threat from the forces of atheism and Communism abroad, and social disorder at home (often placed in terms of the ultimate 50’s domestic hobgoblin, “juvenile delinquency.”) Political, religious, and cultural figures tried to find common symbols that could unify resistance to these threats, and the Ten Commandments were a worthy symbol of American civil religion. In particular, this civil religion, often referred to as “Judeo-Christianity” was a theologically bland spiritual soup that encouraged belief for the sake of belief, for the benefit of nationalistic goals and social cohesion. It was creed which could inspire the words of Dwight Eisenhower that “America is founded in a deeply felt religious faith—and I don’t care what it is.”

Those who invoked the Judeo-Christian tradition in the 1950’s (and those who invoke it today) ignore the fact that anti-Semitism was widely practiced and socially accepted prior to World War II. In short, before the late 1940’s there was no “Judeo” in the perceived American civil religious tradition. Bruce Feiler, in his exploration of the influence of Moses in America, America’s Prophet, claims that the DeMille film helped shape acceptance of Judeo-Christianity. (Other biblical films of the 50’s and 60’s, especially Ben Hur, had the same effect.) “The Ten Commandments,” Feiler says, “both mirrored and molded the mainstream acceptance of different faith traditions,” into the idea of this unified interfaith American religion. The sheer number of viewers that have seen The Ten Commandments attest to its influence. Feiler estimates that with 98.5 million people seeing the film at the box office by 1959, and the annual television showings around Easter and Passover, it is the most viewed film of the 1950’s.

It was in this setting of anxiety about irreligious tendencies at home and abroad that a little-known judge in St. Cloud, Minnesota helped set in stone–literally– one of the lasting legacies of The Ten Commandments. In the 1940s, wishing to avoid sentencing to a juvenile reformatory a teenage boy who had stolen a car, Judge E.J. Ruegemer instructed the boy to find and keep a copy of the Ten Commandments. Inspired by the eventual success of this alternative sentence, Judge Ruegemer began distributing copies of the Commandments nationally through the Fraternal Order of Eagles, of which he was a member, starting in 1951. The F.O.E. distributed 100,000 printed copies of the Commandments and 250,000 copies of a comic book called “On Eagle’s Wings” promoting the organization’s belief in the transformative power of learning about the Commandments.

In 1956, DeMille contacted Ruegemer with hopes of using the judge’s service project to help promote his epic film. Funded in part by publicity money from Paramount, DeMille and Ruegemer ordered granite monuments with the Commandments engraved on them to be placed in front of courthouses and in public parks across the country. As seen in the picture to the left, DeMille often sent stars from the film to the dedications. Consistent with DeMille’s claim that the Ten Commandments were the charter of American liberty, the monuments included patriotic symbols like the bald eagle and the American flag, and even the Enlightenment-Masonic symbol of the all-seeing “third eye.”

Several of the monuments still exist around the country, although some were removed as part of community and judicial conflicts over the separation of church and state. In 2005, the Supreme Court case found the F.O.E. monuments constitutional, in a case involving one of the monuments that was placed on the grounds of the Texas state capitol.

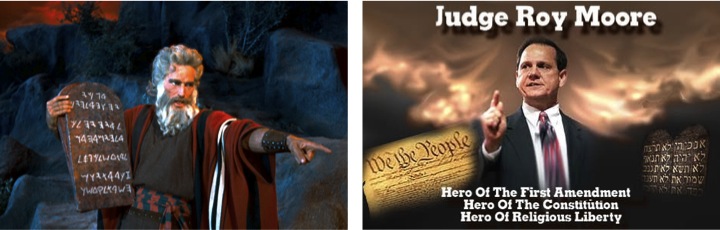

In 2001, forty-five years after the release of DeMille’s film, a more serious constitutional crisis over public displays of the Ten Commandments played out in the South. Unrelated to the campaign of the Fraternal Order of Eagles, Judge Roy Moore, the newly-elected Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Alabama, commissioned a 5,280 pound granite monument to the Ten Commandments. In violation of United States Supreme Court statutes, he placed it inside the rotunda of the state court building. As with the F.O.E. sculptures, inscribed on the monument were passages from the Declaration of Independence, the national anthem, and other writings central to the founding of the United States. Moore announced the placement of the monument using suitably DeMillian language:

“Today a cry has gone out across our land for the acknowledgement of that God upon whom this Nation and our laws were founded, and for those simple truths which our forefathers found to be self-evident…May this day mark the restoration of the moral foundation of law to our people and the return to the knowledge of God in our land.”

The point of the display was obvious: the Mosaic Law was the basis of the founding principles of American democracy. Anyone who has watched The Ten Commandments would find this argument familiar. At the beginning of the film, DeMille makes a personal introduction, beginning with the line, “This may seem an unusual procedure, speaking to you before the picture begins, but we have an unusual subject: the story of the birth of freedom, the story of Moses.” As with DeMille’s film, Moore’s monument (nicknamed “Roy’s Rock”) conflates the Mosaic law with the charter of American democracy.

As with the rhetoric around the Cold War, Moore combined national security interests with fear of moral degradation at home when he invoked the terrorist attacks of 9-11 as an example of the need for moral clarity through religious law:

“Since September 11, we have been at war. I submit to you that there is another war raging—a war between right and wrong.” Then, paralleling the Exodus story, he stated, “For over forty years, we have wandered in the wilderness like the children of Israel. In homes and schools across our land it is time for Christians to take a stand.”

It’s worth noting that for serious scholars of the Bible the concept of the “Ten Commandments” only serves as a synechdoce for a complex matrix of Judaic law as set out in the Pentateuch that addresses everything from food preferences to cultic requirements to community relations among an ancient people. The laws in scriptural form should not be seen as a serious guide to navigating the complexities of modern life. Even the famous passages from Exodus 20, which Judge Moore cited in the creation of his Commandments, had to be heavily redacted in order to be placed on his monument. If taken as the basis for modern jurisprudence, “Thou shalt not covet,” might raise some serious questions about property law once one reads the entire verse in the King James translation:

“Thou shalt not covet thy neighbour’s house, thou shalt not covet thy neighbour’s wife, nor his manservant, nor his maidservant, nor his ox, nor his ass, nor any thing that is thy neighbour’s.”

Under what measure of current law would one’s wife be considered a part of one’s property, equivalent with a piece of livestock?

Those who read, “Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image,” might have serious questions about Moore’s ability to judge cases fairly if they were to read the continuation of that verse:

“I the LORD thy God am a jealous God, visiting the iniquity of the fathers upon the children unto the third and fourth generation of them that hate me.” (KJV)

In Judge Moore’s court, would children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren, and great-great grandchildren be subjected to punishment for the infractions of their ancestors?

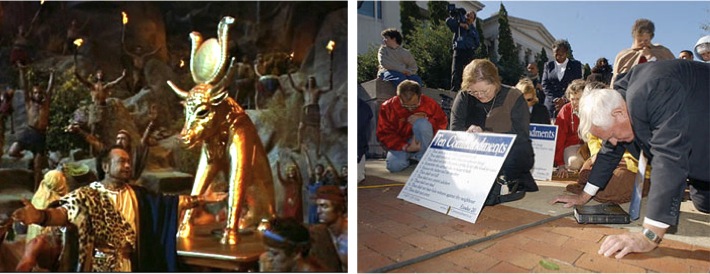

These petty distinctions between what the Bible actually says and what the public perceives as a scripturally based instructions for contemporary living did not stop conservative Christians from turning out in force to support Roy Moore and to venerate Roy’s Rock, some even bowing in worship to the “graven image” Moore had created.

At some point, the distinction between the Mosaic Law as printed in the Bible, and the societal perception of the Ten Commandments has broken down. I would suggest that this is in part because of the tremendous popularity of The Ten Commandments. DeMille’s wildly creative but ultimately misleading adaptation of scripture has insinuated its way into societal perception of scripture until those who have seen the movie find themselves interpreting the scriptural passages through lens of the film. DeMille both exploited and created a cultural reading of the Hebrew scripture and the Exodus story, and was so successful he shaped the perception of this story for generations to come, even up to the modern-day “culture wars” and the stand taken by Judge Roy Moore. During the controversy over Roy’s Rock, a British newspaper referred to Moore as the “Moses of Alabama.” A more accurate statement would be that Moore was Charlton Heston playing the Moses of Alabama.

Clearly Moore believes in the Bible according to DeMille: the conflation between America’s freedom and the Ten Commandments, and the necessity of a religious moral foundation to civil law. But is there a direct connection between “Roy’s Rock” and the Ten Commandments movie? Research into Moore’s statements about the controversy, and a painful read through his autobiography do not reveal an expressed connection; at no point does he say, “I saw this film and it changed my life.” Judge Ruegemer saw a connection, however, between his own and DeMille’s work to promote the Commandments, and the Commandments, and Judge Moore’s monument. In an interview he gave to the Minneapolis Star Tribune in 2003 at the age of 101, Ruegemer stated that, “You could say this big mess in Alabama, where the judge refused to obey a federal court order to remove the Ten Commandments, you could say that all started with that 16-year-old St. Cloud boy.” Whether he realized it or not, Judge Moore was not simply upholding a philosophical concept of the relationship of scripture to civil law, but continuing what is perhaps the longest promotional campaign in the history of film.