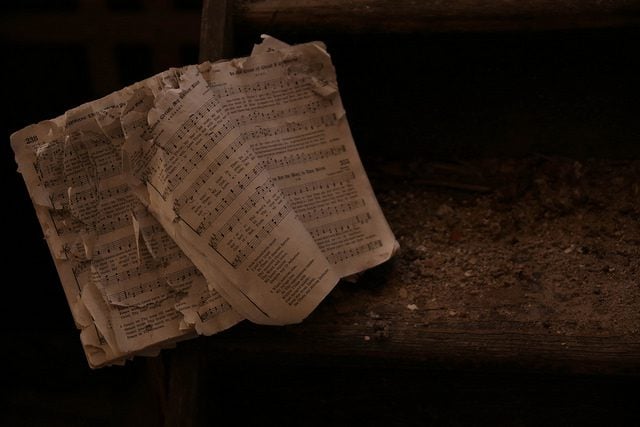

My recent post calling for a boycott of the worship industry seems to have struck a chord. It looks like it may soon become the most successful Ponder Anew post of all time, which I’m thrilled about. It was great to have over half a million people read my post about hymnals, but this one cuts closer to the heart of what it means to be a worshiping church, and the idea of gathered worship as the church’s ethical responsibility.

I’m certainly not against new music. Quite the contrary – I think there’s something drastically wrong if we’re not singing new music, both chronologically recent music and music that is new to us. I’m not against people making a living as a church musician or being compensated for the things they create. I am against the church’s worship being controlled by an industry, and I’m concerned about how that industry contributes to the continued withering of created beauty in gathered worship, and the overall loss of liturgical purpose.

A number of the comments I received on this post (before I ultimately had to shut them down) indicated that disarming the worship industry was a great goal, but that there seemed to be no alternatives other than a return to strictly hymn-based worship, which even if it were possible, it would cost careers and incite anger.

For those of us who already don’t rely heavily on the worship industry, a boycott isn’t going to be that difficult. Perhaps we refrain from buying its music for personal enjoyment, and we work diligently to maintain a strong tradition of congregational music-making. But for others of you, breaking free from the worship industry will take time, and in many cases, a complete boycott just isn’t immediately practical.

In that case, think of some practical steps you can take to move away from the pervasiveness of the worship industry. After all, at the core of this issue is allowing the people to be the primary voice in congregational singing. Step by step, help your congregation break its reliance on a Hillsongized method of doing music, where singing is something done to the people in the way of the commercial recording, instead of done by the people in enriching and varied ways. Here are a few suggestions.

Diversify Your Accompaniment

In other words, move away from the cover band and find ways to pull more confident and musical singing out of the congregation. Look for more acoustic options that are present in your congregation. In all but the smallest of churches, you likely have untapped resources.

Maybe you’re one of those fortunate congregations that still meets in a sanctuary with an organ. Dust off the console, and find ways to integrate the king of instruments. It’s palatte of sounds is immense and diverse, and it’s versatile enough to find a place in nearly every musical style.

Perhaps you have string players. You could use piano accompaniment in place of guitars or synthesizer. Maybe add brass and timpani, or a wind ensemble.

Scale down the percussion from time to time. The trap set does little to encourage good singing.

Try singing acappella. Yep. No band, no amplification. Just a congregation of voices proclaiming the sacred story through song.

Look for Other Streams of Congregational Song

Whatever instrumentation you use, help your congregation rediscover the riches available in the hymn tradition. Add one hymn on a Sunday, and occasionally choose one that most who attend commercial worship services won’t know. There are plenty of great choices on this list.

But you don’t have to stop there.

Sing new hymns. People are still writing them all the time, but because they’re produced outside of the worship industry, they haven’t found widespread appeal.

You can sing gospel and Sunday School hymns.

You can sing folk hymns.

You can sing Catholic renewal hymns.

You can sing songs from the Taize and Iona communities.

You can (and should) sing Psalms.

You can sing chant. It’s not really all that hard, and the results can be glorious.

You can sing African-American spirituals.

You can sing world music.

You can write our own songs in any of these styles.

You could even extemporize new songs among ourselves (like the spiritual songs Paul was talking about).

Vary Your Method of Singing

Sing loudly. Sing softly.

Alternate men and women singing stanzas themselves. Or maybe children. Or sing antiphonally. Or have a solo vocalist sing one. Or have a choral stanza. Or an instrumental stanza. Or an interlude.

You can sing unison. You can sing harmony. You can sing with a soprano descant. Or an instrumental obbligato.

You can crescendo to a full, robust, earth-shaking final stanza. Or decrescendo to a prayerful whisper.

You can vary the harmonization. We can modulate. Hillsongized bands can too, of course, be we can do so in so many different ways.

Above all, break the dependence on the worship leader lead singer. Singing into a microphone with affected vocals and a strained look on your face (my friend Miguel Ruiz describes it as being somewhere between sex and constipation) isn’t really helpful. If possible, get away from singing into a microphone as a soloist would. If amplification is necessary, sing with good diction and a pure tone to set an example. Think of the congregation as a choir, not an audience, and it’s the leader’s job to get them to sing as well as possible. And yes, singing well counts. It’s in and of itself an act of worship. Congregational singing was never about giving people the illusion of a mystical Jesus connection. It’s a formative, didactic, proclamatory discipline, and we have a responsibility to help the people do it well.

We never become worship superstars. We may not get rich. But in the end, after lots of growth and practice, we’ll have something so much more enduring. We’ll know how to sing. We’ll know better why we sing. We’ll have a balanced repertoire from which to sing. The suggestion that we need commercial worship for the sake of diversity, innovation, or freshness just doesn’t make sense. Our options for vital, varied, diverse music-making extend way outside the bounds of what the industry thinks is marketable.