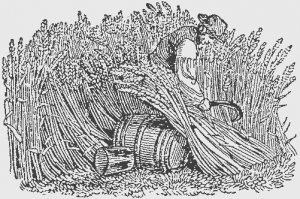

This time of year is marked by the burning rays brought down by the Dog Star Sirius, signaling the scorching heat that can come during the “dog days” of summer. The same light that provided nourishment for the green world now parches the earth. This is the last gasping breath of summer, whose days have grown steadily shorter since the solstice. The dark god of the Wildwood, leader of the Wild Hunt comes to claim his throne. The light god of the green that has ruled this half of the year is sacrificed to ensure the cycle continues. This is Lammastide.

Lammas or Lughnasadh refers back to the ancient rite of offering the first fruits of the harvest to the Old Gods to ensure a safe and bountiful harvest time. Lammastide, and the sacrifice of the first harvest ensure that the rest of the harvest season will also go smoothly. The period of the agricultural cycle lasts from the beginning of August to the autumn equinox in late September. Its main themes are sacrifice and death. The sacrificial blood of the god king is sacred and fertilizes the land. The sacrifice of the god heralded his transition from the world of the living to the world of the dead. The Lord of light that has ruled the waxing half of the year; after his descent to the underworld becomes his shadowy twin the Lord of the Waning Year. The accompanying rituals are about transition and spiritual transformation.

Lughnasadh was one of the four major fire festivals of the Celtic people, and later it became known as Lammas by the Anglo-Saxons. The fire festivals marked the midpoints between the main quarter holidays determined by the Sun’s position. They marked liminal times of transition between the solstices and equinoxes.

In many places throughout the Northern Hemisphere, Lammastide marks the time of the year when agricultural peoples would begin their first harvest. The crops of grain and green herbs that had been planted earlier in the season are ready to be brought up from the ground. Offerings must be made in thanks to the spirits of the land, the individual plants themselves, and the gods and spirits of nature in general. The sacrificial rites of Lughnasadh appease these spirits and ensure a bountiful harvest season. These offerings emphasize the symbiotic and reciprocal relationship within nature.

The Celtic namesake of Lughnasadh comes from the mythos of the god Lugh. A deity worshipped across many cultures, and nearly universally recognized by the Celts; Lugh was known throughout Europe. He is a patron of the arts, master of crafts, and known for his many diverse talents. He is equated in the writings of Julius Caesar to the popular Roman equivalent Mercury. The polytheists of antiquity had an interesting worldview that afforded them the capacity to recognize common attributes in various foreign deities. It was a common polytheistic belief that is stated in the writings of Julius Caesar, that the Celts worshipped the same deities as the Greeks and Romans just under different cultural names.

The transmission of occult knowledge, the arts and crafts, to humanity was a common theme in various ancient cultures. Various mythologies from different cultures and time periods shared this similar idea of divine beings descending from above to teach mankind the skills that would become the arts and sciences, allowing primitive man to become more godlike. Some saw the deification of man to be the greatest transgression. As we see in the ancient Greek myth of Prometheus who is eternally punished for bringing the “fire of inspiration” down from Olympus. If we look across various polytheist cultures across Europe and the near east we can find corresponding figures in each pantheon that fit the description of a messenger-type god of communication, bringing heavenly knowledge which is used to teach humanity various crafts.

In Pagan traditions, specifically witchcraft, we see this as a recurring theme. Deities like Hermes and Mercury, Prometheus and Thoth were all gods versed in multiple arts and skills. They can be connected by their similar attributes and corresponding natures. These teaching gods often follow common themes of illuminating light, connections to the spirit world, and acquiring occult knowledge through sacrifice. Alternatively, the angel Lucifer shares many of these similar traits as well, being part of the same Promethean archetype as gods like Odin, who sacrificed himself on the world tree to gain the knowledge he sought.

However, since this is Lughnasadh I would like to focus on Lugh known also by his Latin name Lugus. Lugh is another deity that fits this archetype perfectly. The well-known god of arts and light was often equated to Mercury also a patron of various craftsmen. Another light bearing divinity sharing not only common characteristics, but also similar linguistic roots is Lucifer. Both deities’ names share a similar proto-Indo-European root, leuk-“flashing light”, which likely branched out into its various other forms of the word.

Interestingly, the figure of Lucifer shares many commonalities with Lugh, and other wandering gods of the sorcerous road. In a common Promethean theme, these wisdom deities bring knowledge of all the arts to mankind. Both of these deities have associations as bearers of the illuminating light of gnosis.

In antiquity, Lugh is equated the Roman god Mercury. He is often found depicted as being surrounded with solar energy. Like the other Promethean gods, he is also a trickster and master of all cunning arts. Lugh is a god of the forge, which has many associations in traditional witchcraft such as the Clan of Tubal Cain. There is much sacred symbolism and myth attached to smithcraft and masonry. Lugh, and beings like him were believed to have come to earth and taught artisans, musicians, bards and craftsmen their art.

Lugh is known for his many diverse talents. He became associated with grain in Celtic mythology. This is where the themes of abundance and sacrifice for the first harvest come in. During this time, we reap what we have sown. One of the oldest sacrificial tropes comes from Sumerian mythology. The god Tammuz was slain and his lover Ishtar stopped nature itself to follow him to the Underworld. This idea of sacrifice goes back to the beginnings of humanity, and those who prayed to the Elder Gods.

During this time remember those Elder Gods that brought us the gifts that helped elevate us to the greatest celestial heights, and showed us the darkest occult secrets of the underworld. The sacrifice of many before us has paved the way for us to practice how we wish, and have unlimited access to all of this knowledge. So when you are contemplating themes of abundance this year, also remember the sacrifice that it took to achieve that abundance.