Editors’ Note: This article is part of the Public Square 2014 Summer Series: Conversations on Religious Trends. In collaboration with the ONE Campaign, the Evangelical Channel is focusing on evangelical responses to the AIDS crisis. Read other perspectives from the Evangelical community here.

By Jay Hein, author of The Quiet Revolution

Dr. Joseph Mamlin had perfected the balance between compassion and realism required of all doctors in the developing world. He could save a few but he could not save them all. So when he walked through the dimly lit Bay 3 of the Indiana University hospital in rural northern Kenya, he became alarmed to see one of his fresh-faced medical students agonizing at a dying patient’s bedside.

Mamlin counseled the doctor-in-training on the fine art of keeping appropriate emotional distance as a survival technique. “But it’s Daniel,” shot back the intern. Sure enough, the dying patient was one of their fellow medical students, Daniel Ochieng, who represented the Kenyan side of the IU-Kenya medical partnership established in 1989. A twenty-four-year-old from Kisumu, Daniel hid his illness from family and friends as was often the case with AIDS in Africa during the 1980s-90s. The disease’s debilitating nature and sure-fire death sentence coupled with wild rumors about how it spread resulted in harsh social exclusion and discrimination. It was much simpler to keep this turmoil a secret.

However, the disease’s ravaging effects soon became impossible to disguise and the pain too great for Daniel to keep it hidden any longer. He was transformed from a vital, promising doctor to hopeless patient as his body was unable to fight off the fast-encroaching infection. Consistent with the disease’s predictable toll, his body began to break down with symptoms ranging from severe coughing, the loss of sight in his right eye, oral thrush which coated his mouth with a cotton-like substance and a diagnosis of tuberculosis.

During Mamlin’s first tour of duty as IU’s physician-in-residence in 1992-93, he watched about 85 Kenyans die from AIDS, most of them in their 50s. Now merely seven years later, he had 1,000 patients filling the same ward and the average age collapsed to 30. Mamlin knew that death for these thousand would be excruciating and relatively short. He tried to convince himself that Daniel’s status as a medical student should not cause him to ignore his own advice about not becoming emotionally involved. But he could not. He did indeed feel responsible for one of his own and couldn’t shake the notion that he had the power to heal him.

While he could not save a continent that was host to the world’s greatest health pandemic, he had an unshakable burden to save this one life. He also knew that he couldn’t do it alone. Global health developments were moving in his favor. While the AIDS patient trend line was racing upward, the cost for treating patients was slowly but steadily inching downward. He returned to the IU Guest House from the hospital, sat at his computer and typed a note to his stateside colleagues asking for help. It would cost approximately $20,000 a year to keep Daniel alive. Could they muster enough Hoosier generosity to make it happen? He didn’t have to wait long for an answer. A doctor from Indiana University’s medical school offered to send the money personally.

Little did they know that the return on this charitable investment would be not only a life saved but also a pivot point in the world’s response to the AIDS pandemic. Fifty pounds underweight and too weak to leave his own bed, Daniels’s recovery from the dead resembled a modern day version of the biblical Lazarus. Mamlin would later remark that seeing one person come back to life while all others around him were dying “was one of the most miraculous experiences medically that I’ve ever had.” Once back on his feet, Daniel became outreach coordinator for the IU-Kenya and an ambassador for “Lazarus Effect” across sub-Saharan Africa desperate for hope.

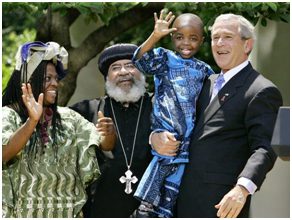

Mamlin did not think he could save a continent but there was someone in the Oval Office pondering whether to do just that. A new American president had taken office following a closely pitched 2000 election campaign where the subjects of Africa and AIDS were unmentioned. Yet, George W. Bush was an advisor to his father’s presidency in the early 1990s and the elder Bush took an active interest in the emerging disease and he was eager to do something about it.

Now ten years after that briefing, the younger Bush could be pleased that so much progress had been made on the response to domestic AIDS. Treatment regimens continued to improve and become more affordable. High profile cases such as NBA star Magic Johnson demonstrated that patients could live a quality life while managing the disease. However, the experience was still hopeless in the developing world. Africa possessed two-thirds of the world’s AIDS cases deaths even though they had less than 10 percent of the world’s population. Worse, and opposite the courageous and smiling example of Magic Johnson, virtually all of Africa’s AIDS cases resulted in being outcast before a lonely death.

On June 19, 2002, President Bush said that HIV/AIDS “staggers the imagination and shocks the conscience” before announcing a new $500 million initiative to prevent Mother-to-Child transmission of HIV/AIDS in the hardest hit regions of Africa and the Caribbean. This was the world’s first full-scale assault on the deadly disease outside the borders of rich nations. It was unilateral action and simply a warm-up act to what the president would announce six months later in his 2003 State of the Union address: a $15 billion plan known as the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, soon to be widely known as PEPFAR.

While America’s solution was unilateral, the President clearly could not do it on his own. He needed congressional approval and public support and he found it in an unlikely alliance formed by a curmudgeonly U.S. Senator, an Irish rock star and a Southern Baptist preacher. The biggest obstacle to Bush’s plan becoming reality was the imposing figure of Jesse Helms, an unreconstructed Southern conservative who was fond of saying that foreign aid amounted to pouring money down a rat hole. As chairman of the powerful Senate Foreign Relations committee, he could do more than talk. He could stop the Bush plan before it even began.

Senator Helms was far more multi-dimensional than his public caricature, however. His opposition to foreign aid was not reflexive but rather a principled rebuttal of the Cold War strategy deploying humanitarian assistance to win friends among corrupt regimes. His close friend, the evangelist Franklin Graham, eulogized him in 2008 by recalling Helms’ confession at Graham’s Christian Summit on HIV/AIDS that he should have done more for the suffering.

The summit itself was a breakthrough in AIDS politics. Hosted by the conservative Graham and his Samaritans Purse charity, he made a confession in his own right. The son of Christian statesman Billy Graham said that evangelical Christians had not done enough to help people with HIV/AIDS. The Baptist Standard reported that Franklin Graham’s 2002 “Prescriptions for Hope” summit in Washington was “part Christian theology lesson, part AIDS education program and part pep rally for social ministry.”

It is one thing for Helms to be persuaded by Franklin Graham, a fellow North Carolinian and ally but it was even more remarkable for the 80 year-old, five-term Senator to be lobbied while propped on his four-prong cane backstage at a U2 concert in 2001. But it was actually the U2 front man Bono who helped convert Helms to the Africa mission. Bono challenged the Senator with the Bible’s verses about poverty, notably Matthew chapter 25 (“I was naked and you clothed me”). The Senator was moved and the stage was set for his partnership with Graham and his eventual legislative work on Capitol Hill.

Thus it was a troika of executive branch, congressional, and cultural leaders—on the stage and in the pews—who moved the African AIDS epidemic front and center while the rest of the world either tearfully mourned or willfully ignored its victims. President Bush, Senator Helms, Bono and Franklin Graham were among the American leaders who considered it an unacceptable crisis. Each believed that there was a biblical mandate to do something about it.

Faith was at the heart of the policymakers’ motivation just as faith-based groups were at the center of the program’s implementation. A 2008 Gallup Poll taken in 19 African nations indicate that 76% of Africans reported trust in faith-based groups, higher than any other organization including government and the police. For their part, the Bush administration knew that it needed to rely on indigenous charities to deliver the services rather than Western ones that would leave the villages when the program ended. Therefore, more than 8 in 10 PEPFAR grantees were African faith-based and community organizations.

I was privileged to lend a modest hand to this work as President Bush’s faith-based director in 2006-08 and I recount more of these compassion-in-action stories in a new book called, The Quiet Revolution. The book title surely captures the African health miracles over the past ten years. Before PEPFAR, African mothers did not name their babies for three months for fear of premature death. Today, Secretary of State John Kerry is presenting the idea of an AIDS-free Africa scarcely more than a decade ahead.

The Indiana University health care program exists because a Christian philanthropist sponsored the travel by several young docs to set up shop in Kenya. PEPFAR exists because an American president understands the scriptures to teach that African AIDS patients are equal in God’s eyes to our citizens and family members. This radical belief can trace its arc to the early Christian church whose members ran into the Roman plagues to care for dying babies as even their own family members ran out of the cities for sake of their own lives.

The church has always been the first responder to human distress and its response to the AIDS crisis is no exception. Yet, it has been far from perfect. Balancing the axis of truth and grace requires an uncommon love for those who hurt while attempting to prevent such pain in the first place. Too often the church’s axis tilted more heavily toward judgment over compassion. Now it must ensure that it seeks to ennoble lives even as it continues to rescue and restore. The church is the hope of the world because it sees not victims but imago Dei. This partnership between Patheos and ONE represents a study bridge to traverse this perilous landscape. Its overriding message is clear: we must continue to put our faith in action.

Jay Hein is president of Sagamore Institute and a fellow at Baylor University’s Institute for the Study of Religion. He is also author of The Quiet Revolution: An Active Faith That Transforms Lives and Communities.

Jay Hein is president of Sagamore Institute and a fellow at Baylor University’s Institute for the Study of Religion. He is also author of The Quiet Revolution: An Active Faith That Transforms Lives and Communities.