A guest post from Mark Tooley, President of the Institute on Religion and Democracy:

*

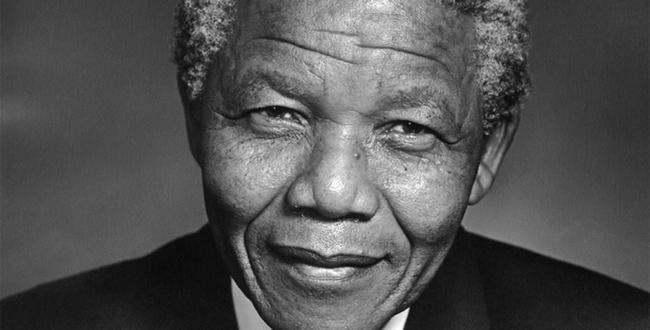

Amid all the justified accolades for Nelson Mandela there’s been some online skirmishing between a few on the right insisting Mandela was a Marxist and some on the left lambasting prominent conservatives 30 years ago (William Buckley, Richard Cheney) who condemned Mandela. Neither seems to appreciate the full arc of history and instead both score their points as though history stopped decades ago.

After Mandela gained release from prison in 1990, some oldline U.S. church denominations like the United Methodists created a Nelson Mandela Freedom Fund and presented him a large check during his U.S. visit. Many church members were enraged. Oldline denominations had already controversially donated many thousands over the years to the World Council of Churches Program to Combat Racism, which disbursed hundreds of thousands of dollars in grants to Mandela’s African National Congress and other military liberation groups in southern Africa, including SWAPO in Namibia and, earlier, the MPLA in Angola and FRELIMO in Mozambique, plus Robert Mugabe’s Patriotic Front in then Rhodesia. Some of these groups were explicitly Marxist. The ANC was not but worked in alliance with the South African Communist Party.

Twenty four years ago it was not yet clear what sort of leader Mandela would be after 27 years in prison. Before incarceration, he had founded the ANC’s armed wing, the Spear of the Nation. He had publicly lauded the Soviet Union, supported North Korea’s invasion of South Korea, and although apparently never a Marxist Leninist or Communist Party member, certainly identified with the hardline liberationist left. Even after release, Mandela did not disavow armed struggle. And he visited and publicly acclaimed some of his unsavory patrons over the years, including Libya’s Muammar Kaddafi and Cuba’s Fidel Castro. Some liberal bloggers have complained that conservative critics of Mandela in the past picked the wrong side of history. But Mandela himself, when aligning with now disgraced or dead dictators, made his own seeming choice for the wrong side.

The U.S. never “supported” Apartheid South Africa, whose Boer rulers, unlike the English whom they displaced, had not sided with the Anglo-Americans during either world war. But neither was it in U.S. interest for mineral rich and strategically placed South Africa (which also eventually had nuclear weapons) to degenerate into civil war or succumb to bloody Marxist “liberation,” as happened to neighboring Angola and Mozambique, abetted by Cuban troops and East German advisors. Oil rich Angola’s acquisition by the Soviet Bloc was especially a grievous blow.

In the midst of the Cold War, U.S. officials, not just conservatives, primarily saw the ANC as a violent, Soviet-backed insurgency. Why would the U.S., during those years, have advocated for the proxy of our totalitarian adversary, much less its once outspokenly anti-U.S. leader who founded its military wing? The U.S. had more common cause with peaceful opponents of Apartheid among South African blacks and English speaking whites.

Among the countless blessings of the relatively peaceful fall of the Soviet Bloc was that it removed the threat of a Marxist South Africa, freed previously intransigent Afrikaners to negotiate a surrender of their power, and incentivized the ANC to identify with the democratic West. Mandela shrewdly realized that his nation needed peaceful reconciliation, not retribution against his former oppressors. Just as importantly, he pragmatically abandoned most of his former anti-Western rhetoric and implicitly embraced the new U.S. led world order of market economies and mostly democratic rule. Thanks to his restraint, wisdom and prudence, South Africa’s whites did not flee, blacks did not seek vengeance, private property was mostly protected, and democratic structures were refined if not perfected. Unlike neighboring Zimbabwe, the former Rhodesia, impoverished by Mugabe’s 33 year socialist dictatorship, South Africa is today a relatively prosperous and comparatively functioning society.

Some critics, and not just conservatives, have faulted Mandela for not speaking out on behalf of peoples oppressed by the dictators who supported him. It’s unclear whether his silence was indifference to their plight or a sophisticated political calculation. Unfortunate to be sure, but Mandela ultimately was a realist and a nationalist, who cared primarily about his own nation, not global causes. His focused pursuit of national interest, as he understood it, was, from a certain hardheaded perspective, commendable. He sought to lead his nation, not achieve canonization.

American presidents have pursued our country’s interest with their own ruthless, pragmatic necessity across the decades. Yes, America supported unpleasant right wing dictatorships during the Cold War, but also far worse Marxist ones. Some conservatives still fault FDR’s assiduous courtship of Stalin, one of history’s greatest mass murderers. But the Soviet Union absorbed 90 percent of Allied casualties during World War II, and defeat of Hitler’s Germany would have been nearly impossible without it. Hardly naïve, FDR on its dying day remarked he got along with Stalin fine but thought he likely murdered his own wife. During the Cold War the U.S. also effectively allied with Yugoslavia’s repressive Communist dictator, Tito, who broke with the Soviets. America even flirted with Romania’s horrendous Ceausescu, who sometimes defied Moscow, and who gave President Nixon a rapturous welcome. Nixon’s rapprochement with Mao’s China was strategically brilliant but placed America alongside another appalling mass murderer and slave master, although a needed counter to the Soviet Union.

All national leaders, especially in urgent times, must necessarily make distasteful choices for the greater good if not the survival of their people. In his struggle against the Boer led Apartheid oppression of his nation’s black majority, Mandela sought help from wicked sources, whom he never explicitly disavowed, but whose example he ultimately rejected. He was not unlike America’s WWII and Cold War leaders who also made unlikeable but needed allies for the good of their nation and also ultimately the world. Critics of both don’t realize the similarity.

Mandela is widely hailed as a saintly humanitarian. But he deserves more credit as a patient, calculating, persevering, disciplined patriot who prioritized his nation over himself and others. He performed what Providence ordains leaders at decisive moments to achieve.