This marks the end of “seminary week” for me here at Philosophical Fragments. We’ll return to the regularly scheduled programming next week.

In “Sex at Seminary” (and followup pieces here, here and here), I’ve made the case that seminaries should give greater attention to the moral and spiritual formation of their students. In some cases, seminaries striving for credibility within the academic world have raised the quality of their faculty and their course offerings but not (yet) raised the quality of their spiritual formation program. I’m aware of some healthy developments along these lines at PTS and elsewhere, but I just want to offer my thoughts.

Emphasize Obedience

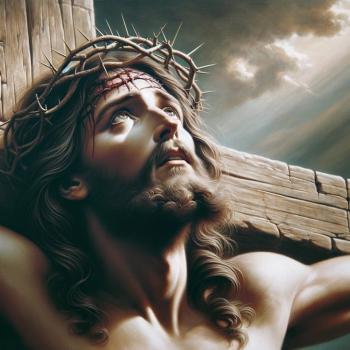

As I argued in “Does Obedience Matter?“, there is a profound and enduring relationship between practicing obedience to the will of God as best we understand it and enjoying a healthy, growing and maturing spiritual life. It has been, absolutely without exception, the times when I have most disregarded the ethical teachings of Jesus that I have experienced the greatest distance from God and the greatest regression in my faith. Christ consistently calls for those who love him to follow him, keep his commands, and feed his sheep. All of these are matters of obedience. Lest I be misunderstood: our obedience does not win our salvation from God. It is not the basis upon which we are saved. But obedience matters. It matters a lot.

The reasons should be made plain to seminary students. We imitate Christ when we obey his command to love our neighbor and pray for those who persecute us; we imitate Christ when we obey his command to care for the least of these; and we imitate Christ when we obey his command not to look lustfully upon a woman who is not your wife. We honor God when we respect his Word and steer clear of adultery, fornication, impure thoughts, and unclean talk. In imitating Christ, in following in his footsteps, we enter into the experience and life and love of Christ — we come to know Christ and the God he reveals. In honoring God, we are reminded of God’s Lordship and his goodness. And in seeking to live lives of obedience, we turn to the power of the Spirit, and more and more we experience the indwelling of the Spirit.

The reasons should be made plain to seminary students. We imitate Christ when we obey his command to love our neighbor and pray for those who persecute us; we imitate Christ when we obey his command to care for the least of these; and we imitate Christ when we obey his command not to look lustfully upon a woman who is not your wife. We honor God when we respect his Word and steer clear of adultery, fornication, impure thoughts, and unclean talk. In imitating Christ, in following in his footsteps, we enter into the experience and life and love of Christ — we come to know Christ and the God he reveals. In honoring God, we are reminded of God’s Lordship and his goodness. And in seeking to live lives of obedience, we turn to the power of the Spirit, and more and more we experience the indwelling of the Spirit.

This, I believe, is why the Psalmist speaks of loving God’s law. As Paul makes clear, the Law convicts us of our sinfuless and prepares us for the reception of divine grace. But it also teaches us about the cares and the character of God. As Kierkegaard would say, we should be grateful because we know what the task is. Do you know what a blessing that is? Do you understand how much time the world can waste in wondering what we are supposed to do, how we are supposed to behave, and how we are to care for one another? The ethical teachings of the Bible provide us with the answers to those questions. They tell us how we should then live. And they give us a path into the company of God, a path to spiritual maturation.

I’m not advocating a seminarian’s version of a police state where adherence to biblical teachings on personal ethics is enforced with flashlights and batons. (There is something to be said for codes of behavior, and some seminaries have gone too far, and some not far enough, in setting standards of behavior for their students.) But I’m talking about the kind of prevailing ethos that’s cultivated and fortified by what the faculty and administration say in public venues.

Combatting the Idols

Sometimes seminarians can feel like “the chosen ones.” We can get away with the little things, because we’re giving our lives to God’s service. And just like the favored child or the favored student feel like they can push the boundaries a little further than the rest, sometimes we (I) felt that I could let the little things slide. I didn’t need to spend time in the Word because I was studying Hebrew. I didn’t need time in worship because I was exploring the glory of God through the writings of Karl Barth.

It was the idol of Christian intellectualism that led me to scorn the name of Jesus. As I explained in “Finding Jesus (Again) at Seminary,” I had stopped using the name “Jesus” and preferred names like “Christ” or “The Son of God” — names that would go down a little easier at a cocktail party. But in doing so, I had lost touch with the beating heart of my relationship with God: an ongoing personal encounter with Jesus, God-made-personal, the same Jesus who shared my joys and shared my sorrows and shared my sin and gave me his life and grace and righteousness.

I don’t claim to have learned many important lessons yet in life, but I have learned the vanity of intelligence and knowledge in themselves, and the emptiness of a worldly intellectualism. Anti-intellectualism is also a problem, of course, but honestly I feel that the pull of the idol of intellectualism is so strong that I’d be better off amongst the anti-intellectuals than I would amongst the worshippers of intellect.

Paul’s right. It’s all rubbish — compared to the surpassing greatness of knowing Christ Jesus our Lord. So by all means study your theology and history and language textbooks, but remember that they are means to the end of knowing Jesus and making him known.

Recover and Restore the Spiritual Disciplines

I saw some green shoots in this area when I was at seminary, and I know that folks like Dr. Bo Lee have done more along these lines in the years since. That’s fantastic. More, please, and faster.

Seminaries should be, among other things, communities in pursuit of holiness, communities in search of spiritual maturity. The classic spiritual disciplines have so much to teach contemporary Christians. I would love to see seminarians read — together, and preferably at the outset of their program and then repeatedly throughout — Bonhoeffer’s Life Together and Thomas a Kempis’ Imitation of Christ and other works that emerged from communities living intentionally in pursuit of God. Unfortunately, I did not feel that sense of togetherness and common purpose — and I understand it must be extraordinarily difficult to achieve. I felt that there was a conferral of professional capacities, and of the knowledge that pastors, it was felt, should possess. There was a sense that we were, together, pursuing the skill of pastoring (although I was more an academic student, I also wanted the pastoral training). Yet I would have loved a deeper sense that we are, together, pursuing an ever-deepening and ever-maturing relationship with Christ.

Discipleship too should be a critical part of any seminary education. Pairing students with individual faculty or other pastors in the area who can speak truth into their lives. Also, though a Protestant, I’m a deep believer in confession. A friend of mine, Adam McHugh, has made the case that all pastors should be in therapy. I would say that all pastors, and all pastors in training, at least need places where they can confess and be held accountable. From the feedback I’ve received from this series, I’m gathering that too many seminary students feel alone — separated from meaningful relationships with peers who share their convictions, but also without the help and guidance of an older generation. A network of disciplers, perhaps even a different discipler each year, would be a worthy investment for any seminary.

Finally, I think it would be beneficial to set seminary students on “rounds” similar to what medical students receive. I got insight into prison chaplaincy and youth ministry, but (even though I enjoyed those immensely) I think I would have benefited even more from spending a couple months in prison chaplaincy, and a couple months in youth ministry, and then a couple months each in hospital chaplaincy, military chaplaincy, parish ministry, elder ministry, evangelical outreach, and so forth. This would take a significant investment in the infrastructure to pull it off, but I believe the payoff would be huge.

So what do you think? What else can seminaries do to strength the moral formation they provide their students? I don’t believe for a moment that this exhausts the list of solutions. It’s only, at best, a beginning. Let’s think creatively together.