Despite a rocky history, Mormons have come to love free trade. They should keep advocating for it in the face of Trump’s skepticism.

An ancient text describes a group of people who benefited from open borders and free trade. But it isn’t British economist Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations, but rather the Book of Mormon, a collection of scriptures revered by members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Its description of a borderless trading regime is set out in the following verses:

“And it came to pass that the Lamanites did also go whithersoever they would, whether it were among the Lamanites or among the Nephites; and thus they did have free intercourse one with another, to buy and to sell, and to get gain, according to their desire. And it came to pass that they became exceedingly rich, both the Lamanites and the Nephites; and they did have an exceeding plenty of gold, and of silver, and of all manner of precious metals, both in the land south and in the land north.”

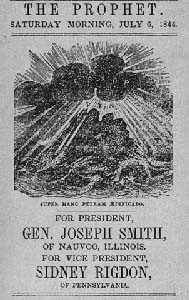

The implication of these verses is clear – free trade and freedom of movement enable markets to allocate labor and resources in an efficient manner that leads to increased prosperity. However, although their foundational scriptures endorse free trade, Mormons have had a somewhat mixed relationship with the concept. For example, the founder of Mormonism, Joseph Smith, when running for President of the United States in 1844, published a pamphlet that called for a “judicious tariff.” And later, in June of 1930, Reed Smoot, a Mormon apostle and U.S. Senator, cosponsored the disastrous Smoot-Hawley Act, a statute that drastically increased tariffs, helped spark a global trade war, and exacerbated and prolonged the effects of the Great Depression.

Since the folly of the Smoot-Hawley Act, most Mormon politicians have learned from the mistakes of the past. Democratic Representative Mo Udall, a Mormon from Arizona, was one of the cosponsors of legislation that paved the way for the negotiation of NAFTA, and former Utah Governor Jon Huntsman helped facilitate China’s accession to the World Trade Organization when he served as Deputy U.S. Trade Representative. The heavily Mormon state of Utah has embraced free trade wholeheartedly – from 2005 to 2014, Utah’s exports to nations covered by free trade agreements increased by 165%, and the Utah legislature has aggressively pushed “immersion” language learning programs in the state’s schools to enhance workers’ ability to engage in international commerce.

Granted, some Mormons have continued to express skepticism about trade. Former Democratic Senator Harry Reid, a Mormon from Nevada who recently stepped down as the Senate Minority Leader, was notorious for his opposition to trade agreements, voting against 15 such pacts, including NAFTA and ones with Oman, Peru, and South Korea. Democratic Senator Tom Udall, a Mormon from New Mexico, has also been skeptical about trade, voting against many of the same agreements that Reid opposed. But the opposition of Reid and Udall only marks them as distinct outliers among their coreligionists in government, most of whom have touted the benefits of trade.

Going forward, however, Mormon politicians will be faced with some distinct challenges when it comes to their embrace of trade. President Donald Trump has broken with decades of free trade advocacy by both Republican and Democratic presidents by threatening to leave NAFTA, withdrawing from the TPP, and suggesting that he might ignore decisions of the World Trade Organization, an international body that adjudicates trade disputes between nations. Although Arizona Senator (and Mormon) Jeff Flake implicitly condemned such stances by recently defending NAFTA in a statement to The Arizona Republic, he’s up for reelection in 2018 and may be tempted to downplay his pro-trade bona fides in the face of a Trumpite primary challenger. Similarly, Utah Senator Orrin Hatch has lauded NAFTA as a “strong anchor” for North American markets, but he also faces reelection in 2018 and may soften his trade advocacy to survive a primary (it should be noted, however, that Hatch may be in a better position than Flake – he has been a strong Trump ally). To put it bluntly, Mormon politicians may be forced to choose between their commitment to trade and their political survival – it could be hard for them to win reelection if they oppose their own party’s president.

Mormon politicians have a mixed record when it comes to free trade, though they have largely come to embrace it over the past few decades. In the coming disputes between Trump and Congress over U.S. trade policy, Mormon pols who wish to be remembered kindly by history should keep in mind the lessons of scripture, and the disasters of the Smoot-Hawley Act, by continuing to advocate for free trade.