My grandfather took a train to Toronto, Canada, to start his LDS mission in 1948. After a very brief stay at the mission home, he was off with his new companion to find converts. The Church was very small at the time in the area. Big cities like Toronto and Oshawa had branches, but most small towns lacked a single member and the missionaries were left to travel long distances, usually once every few weeks, to neighboring villages in order to gather with missionaries and have a makeshift sacrament service. When they entered towns that lacked any previous LDS presence, which wasn’t rare, they would first find the sheriff in order to get a permit to preach the gospel. There was very little oversight. Though they would write weekly letters to the mission president, they were infrequently visited by authorities and mostly left to their own decisions. They did have a missionary handbook that they were expected to learn—a common mission saying was “Be careful of page 27!,” a reference to the section in the book that cautioned against being alone with a member of the opposite sex—but most lessons were learned through trial and error. While there was some opposition to their message (missionaries didn’t dare to go to the Province of Quebec due to the story of previous elders being stoned), the general reaction was one of apathy. A majority of the missionaries were fortunate to witness one baptism per year.

Learning about missionary work in the late 1940s can seem foreign today—at least it did to me. Last summer, I sat down with my grandfather and had him explain the ins and outs of his mission, the type of day-to-day work they did, the opposition they witnessed, and the protocols they were expected to follow. As expected, it was all fascinating, and a reminder of how much change can happen over a half-century, post-correlation. But what really struck me was their method of, and resources for, teaching and learning.

Missionaries in the 1940s were given very little instruction on what and how to teach. My grandfather claims he received minimal instruction from the mission center in Salt Lake City, and even less when he arrived in the mission field itself. When he went to his first “meeting” with interested listeners, his companion rambled on about the godhead, but the particulars were rather fuzzy, and he remembers not understanding what the heck his trainer was actually trying to say. They would often hold what they called “cottage meetings,” which, in theory, would allow them to speak to large groups of people and, in a dream scenario, lead to mass baptisms; I’m sure dreams of Wilford Woodruff preaching at Benbow Farm were common. But the reality was often sparcely-attended gatherings where ill-prepared young men either read from pamphlets or stumbled through their own recitation of the First Vision.

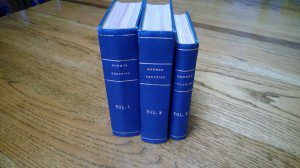

As a result of their limited direction, missionaries were left to construct their own curriculum, both for teaching and learning. Pamphlets written by prominent LDS leaders were thus an important part of missionary life. For many, it was their original source to gospel principles and Mormon history beyond what they learned in sunday school prior to their mission. Similar to the many print-outs and copies-of-copies of “deep doctrine” passed around by missionaries today, Mormon pamphlets were bought, traded, and collected in large numbers. They were used both as tools to teach interested observers as well as studied for private instruction. In 1949, a year into my grandfather’s mission, an idea came to mind: to collect all the pamphlets in circulation and combine them into a more permanent and useful format. So, he took 36 pamphlets, totaling 1,784 pages, bound them into three volumes, and added his own tables of contents that listed the name and length of each insert. He titled these books “Mormon Doctrine.”

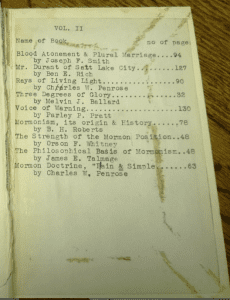

The contents of these volumes are both fascinating and perplexing. Some of the pamphlets are obviously geared toward missionary teaching, like Joseph Smith’s Own Story (a published edition of what we know as “Joseph Smith History” in the Pearl of Great Price), John Widtsoe’s Seven Claims of the Book of Mormon, and James Talmage’s The Great Apostasy, which were the first three inclusions in the first volume, perhaps implying that they were the most frequently used. But others were obviously not for that same purpose or audience: the compilation also contained Joseph Fielding Smith’s Origin of the Reorganized Church as well as Blood Atonement and the Origin of Plural Marriage, two defensive and very specialized arguments that likely had little relevance in rural Ontario. There were others with purposes as disparate as B.H. Roberts’s practical advice in On Tracting to James Talmage’s reasonable Philosophical Basis of Mormonism.

The tracts also took, at times, very different approaches to the gospel. One of the pamphlets, John Widtsoe’s What is Mormonism? An Informal Answer, was intended to replace old paradigms. In 1933, Widtsoe privately wrote that the work was designed for people “who look at religion from an angle quite different from that which filled the vision of the people a generation or two ago,” and though some “may doubt the wisdom of any departure from the old paths,” Widtsoe hoped his approach would find traction within the new culture. Ironically, one of the works I imagine Widtsoe’s pamphlet was meant to replace, Charles Penrose’s Rays of Living Light, an older tract that sought to prove Mormonism through biblical texts, was also bound in the volumes, as was Parley Pratt’s highly millenarian Voice of Warning, a pamphlet that was even more ill-fitted for the twentieth century, thus demonstrating the staying power of an oft-reprinted but increasingly quixotic view of Mormonism.

There are few common themes to be found in these tracts: they made no attempt to be systematic, they failed to be comprehensive of the period’s popular ideas, they included more-than-infrequent disagreements (both explicit and implicit) when comparing the separate works, and, when encountering all the various claims, they remind the reader of children throwing wet spaghetti against the wall in hopes to see which ones will stick. Indeed, many of the arguments found throughout these pamphlets were neither coherent nor consistent, were often speculative, included claims that were disregarded even before the year in which they were bound, and were etched into a cultural moment that was quickly passed by.

So what does it mean that LDS missionaries read all of these divergent, and at times competing, pamphlets in tandem? Why would it make sense for my grandfather to gather all of them together in bound volumes? And more importantly, what do these volumes tell us about the Mormon mind?

Whether intended or not, I think these three volumes of “Mormon Doctrine” embody what I love about Mormonism: the scattered, unsystematic, hodgepodge, inchoate, mixed-bag, contraditory, and paradoxical corpus of teachings and culture that always seem in construction but never finished. Compared to Bruce R. McConkie’s more famous Mormon Doctrine, published the following decade, which claimed to be authoritative, dogmatic, and definitive, my grandfather’s “Mormon Doctrine” embraced an inquisitive nature, an experimental approach, an openness of mind, and a refusal to be bogged down by the niceties of boundaries and systematic theology. Mormonism, I think, is best experienced as an energy and enthusiasm, a willingness to engage numerous ideas through trial an error, and a humility that emphasizes the potential for being wrong at every turn yet the hope that future correction brings broader clarity. Behold the perils and promise of an open canon.

“A foolish consistency,” Emerson once quipped, “is the hobgoblin of little minds.” These three-dozen pamphlets and nearly two-thousand pages—imagined by nearly two-dozen different writers from different backgrounds, written over the course of a radically changed century, printed across the very disparate North American continent, and bound by a twenty-year-old missionary in Ontario, Canada—encapsulate the mish-mash of Mormon thought, history, and culture. Not all of it is persuasive, a good number of it is dismissable, and a fair amount is severely dated, but the core of it is energizing, sincere, and powerful. Just like the missionaries in western Canada in the late 1940s fumbling through their labors with minimal direction or oversight but with a glint of the divine and a devotion to truth, Mormonism is tethered to the imperfections of humankind yet dedicated to a noble purpose. The finished product, when all is bound together, may not be the most pretty, polished, or consistent sight, but it will be a testament to an uneven yet noble balance of both zeal and knowledge.