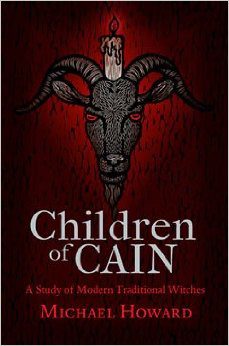

I just got through reading Michael Howard’s Children of Cain: A Study of Modern Traditional Witches (Xoanon Limited, 2011*). Howard’s book is about the alleged Old Craft, sometimes also known as Traditional Craft, an organic Witchcraft that predates Gardner’s version of the same (or a similar) thing. Most of us have run into Traditional Crafters online and sometimes even in person. In my case some of those online interactions have turned into arguments (though that’s never been my intention). So while I’ve disagreed with many who claim to be of The Old Craft, I’ve always been fascinated by the idea of a pre-Gardner Witchcraft. Fascinated, but skeptical to some degree, perhaps even more so after reading Howard’s book.

I just got through reading Michael Howard’s Children of Cain: A Study of Modern Traditional Witches (Xoanon Limited, 2011*). Howard’s book is about the alleged Old Craft, sometimes also known as Traditional Craft, an organic Witchcraft that predates Gardner’s version of the same (or a similar) thing. Most of us have run into Traditional Crafters online and sometimes even in person. In my case some of those online interactions have turned into arguments (though that’s never been my intention). So while I’ve disagreed with many who claim to be of The Old Craft, I’ve always been fascinated by the idea of a pre-Gardner Witchcraft. Fascinated, but skeptical to some degree, perhaps even more so after reading Howard’s book.

I think it’s dishonest to simply dismiss every claim to Witchcraft pre-Gardner. I’m convinced that such groups most likely existed, but I’ve yet to see anything that makes me believe that they are any older than the coven Gardner was initiated into back in 1939. Aidan Kelly has written about several of the alleged pre-Gardner groups online over the last couple of years and those articles are definitely worth reading. My problem with a lot of these claims comes from how the words “Witch” and “Witchcraft” are used.

When I hear the words “Witch” or “Witchcraft” in a Contemporary Pagan setting, I immediately envision a system that’s a combination of the magical and the spiritual. Eclectic Wicca, British Traditional Witchcraft, the Feri Tradition, all of those paths contain both magical practice and direct interaction with the divine. Any sort of “Pagan Witchcraft” has to contain those two elements. Magic and religion are often separate strands of experience. One can practice magic completely free of a religious context, and one can even walk many paths within Pagandom and not necessarily believe in or utilize magical practice.

When I hear the words “Witch” or “Witchcraft” in a Contemporary Pagan setting, I immediately envision a system that’s a combination of the magical and the spiritual. Eclectic Wicca, British Traditional Witchcraft, the Feri Tradition, all of those paths contain both magical practice and direct interaction with the divine. Any sort of “Pagan Witchcraft” has to contain those two elements. Magic and religion are often separate strands of experience. One can practice magic completely free of a religious context, and one can even walk many paths within Pagandom and not necessarily believe in or utilize magical practice.

So when I read about Old Craft traditions being passed down in secret for hundreds years, it’s with a sense of both belief and disbelief. I believe that magical traditions may very well have been passed down for generations, but it’s hard for me to believe that there was much if any spiritual component attached to those traditions. Often times magical traditions can be so easily folded into a Modern Pagan worldview that it might feel as if they’ve been there all along. When someone says my family has been practicing Witchcraft and worshipping the Horned One for generations it’s not necessarily a lie, it becomes a kind of belief, because the spiritual elements end up feeling like they’ve always been there. (The true falsehoods over the years are usually the “grandmother initiation” stories, but that’s a different post.)

So one could have a core set of magical beliefs that have been passed down from the Renaissance and then later those practices are supplemented with Modern Paganism (and often again supplemented by more “complete” magical systems, like that used by Gardner or Robert Cochrane). That result is the creation of a tradition with very old foundations, but it’s not an “Ancient Witchcraft” because it’s a combination of an old strand and a new strand. Besides, it’s unlikely that anyone would have called themselves a practitioner of Witchcraft two or even a hundred years ago. A lot of traditional magical practice was directed against witches. So while many strands of Old Craft might contain magical practices that are hundreds of years old, I’m still not sure that makes any of them older than Gardner’s Witchcraft. It’s worth pointing out that Gardner was most likely initiated into a coven that had its own practitioners of handed-down-family-magic.

So one could have a core set of magical beliefs that have been passed down from the Renaissance and then later those practices are supplemented with Modern Paganism (and often again supplemented by more “complete” magical systems, like that used by Gardner or Robert Cochrane). That result is the creation of a tradition with very old foundations, but it’s not an “Ancient Witchcraft” because it’s a combination of an old strand and a new strand. Besides, it’s unlikely that anyone would have called themselves a practitioner of Witchcraft two or even a hundred years ago. A lot of traditional magical practice was directed against witches. So while many strands of Old Craft might contain magical practices that are hundreds of years old, I’m still not sure that makes any of them older than Gardner’s Witchcraft. It’s worth pointing out that Gardner was most likely initiated into a coven that had its own practitioners of handed-down-family-magic.

In just the first chapter of Children of Cain the argument for a pre-Gardner spiritual-Witchcraft begins to unravel. Howard titles his first chapter Traditional Witch Ways, but nearly all of those ways can be traced to late Nineteenth and early Twentieth Century beliefs.

“The Old Craft is often exemplified by close contact with the spirit world, and acknowledgment of the bright and dark aspects of the witch god and goddess and (in some traditions) the role of the Horned One as both Lord of the Wildwood and Lord of the Wild Hunt. These two aspects are sometimes represented by the Oak King and the Holly King, the twin gods ruling the waxing (summer) year and waning (winter) year respectively, based on ancient Welsh legend.”

All kinds of Witch traditions have close contact with the spirit world, and every Witch I know is well aware of the “bright and dark” aspects of deity. Fifteenth Century witches were certainly alleged to have worshipped a sometimes horned god (the Christian Devil) but the Horned One as a “Lord of the Wildwood” owes far more to Nineteenth Century poetry and Margaret Murray’s The Witch-Cult in Western Europe (1921) than to medieval witch-hunts. The legend of the Oak and Holly Kings is even more modern, only dating back to Robert Graves and his 1948 book The White Goddess. Those are either incredible coincidences (and if they are, there are a lot of Modern Crafters who should be crafting a law-suit against Graves’s estate) or represent new ideas being folded into magical traditions.

Almost all of Howard’s examples as it pertains to deity reflect modern influences. Just a bit later in the chapter Howard writes:

“The witch god is also represented as the sacred king, the ancient vegetation god who suffers a sacrificial death at midsummer, descends into the underworld and is reborn at the winter solstice . . .”

The idea of the sacred king as the ancient sacrificial-vegetation god is old, but it’s old in that it dates back to the 1890’s and the publication of James Frazer’s The Golden Bough. That doesn’t invalidate the ideas, just the idea that they might represent a centuries old Witch-tradition.

Even traditions that feel older because they are a little different from what many of us think of us as the norm can be traced to more contemporary sources. When Howard writes about the covine structure (and a different spelling for “coven” doesn’t necessarily mean much either) I was immediately struck by just how much that structure mirrors ideas found in Murray’s Witch Cult:

“In most traditional groups it is the Magister, ‘Devil’ or witch master who rules the covine and is the MC or ‘master of ceremonies’ presiding over the rituals.”

I feel like I’m being overly cruel to Howard’s book, and I don’t mean to be. There was a great deal in it that I truly enjoyed. Any time I can read a bit more about Robert Cochrane, (The Clan of Tubal Cain) I’m a pretty happy camper. I was also happy to learn more about groups like The Regency** and The Horseman’s Word. (Sadly there was a chapter on the “Pickingill Craft” a frequent topic in Howard’s writing, though there is really no evidence that “Pickingill Craft” has ever existed.) Howard has done Paganism and Modern Witchcraft a real service by documenting the groups in Cain, so while I don’t necessarily agree with all of his conclusions I appreciate the work.

I’m sure that more books on Old Craft will be released in the coming years, and when they are released I’ll buy them (regardless of price in most instances). While a skeptic to some degree, I hope with all my heart that I’m ultimately wrong on the subject of The Old Craft, nothing would make me happier. Proof will require some degree of documentation, and it has to be more than “it’s old because I say it’s old.” Ultimately it doesn’t really matter whether or not Traditional Craft is legitimately older than Gardner’s version. As long as its messages continue to resonate with practitioners it will remain a part of Modern Paganism, and as a result, influence many of us who call ourselves Witches.

I’m sure that more books on Old Craft will be released in the coming years, and when they are released I’ll buy them (regardless of price in most instances). While a skeptic to some degree, I hope with all my heart that I’m ultimately wrong on the subject of The Old Craft, nothing would make me happier. Proof will require some degree of documentation, and it has to be more than “it’s old because I say it’s old.” Ultimately it doesn’t really matter whether or not Traditional Craft is legitimately older than Gardner’s version. As long as its messages continue to resonate with practitioners it will remain a part of Modern Paganism, and as a result, influence many of us who call ourselves Witches.

*If you are interested in picking up a copy of Children of Cain and you live in the United States, all I can say is good luck. Copies are currently selling for about 75 bucks online. I got mine for 60 at Fields Bookstore while at PantheaCon.

**Sadly the history of The Regency is not quite as cool as the name The Regency. Seriously, The Regency might be the coolest name for a Witch-group in practically forever.