You may think the term “secularist deity” is an oxymoron. But it’s important to bear in mind that in the modern sense, the word “secularist” is not the same as the term “secular.” While “secular” frequently means the opposite of “spiritual/religious,” the word “secularist” these days refers to someone who believes in the separation of religion and state, and that all people should be treated equally regardless of their religion or lack of religion.

That’s why I don’t see any conflict between being a secularist and being religious. An increasing number of secularist voices are coming from liberal members of religions speaking out against both wrongdoings within their own religious community, and those who victimise their community. One of the winners of the National Secular Society’s Secularist Of The Year 2018 award was an Anglican vicar – Rev. Graham Sawyer, who has done outstanding work in fighting for justice for victims of abuse in the Church of England.

So it seems natural to me, as a Pagan, to look for inspiration not only from flesh and blood secularists who’ve fought against religious privilege, but also from mythology. I think there are a large number of deities and other mythological figures who can teach us something about secularism. And with April being Free-thought, Humanism, & Secularism History Month, I thought I’d try to write a series of blogs on these deities.

My first post looks at the rebel gods – the ones who defied other, more powerful deities. This is hardly an unusual idea in mythology; every culture in the world has trickster gods and folk heroes.

I think almost any trickster god could be included here. But with there being so many, I’ve restricted this post to mythological tricksters whose rebellion served an important purpose rather than just to cause chaos for its own sake – and a purpose that benefited mankind in some way.

The deities I’ve listed have many things in common, but one important connection is that most of them suffered horribly for defying divine authority. This is sadly reflected in the mortal world – it’s all too true that those who stand up against religious authorities for freedom and human rights find themselves bullied, persecuted and even tortured or killed.

So let these deities inspire you, and if you can, remember them in your practises and think of them when going out to fight for justice.

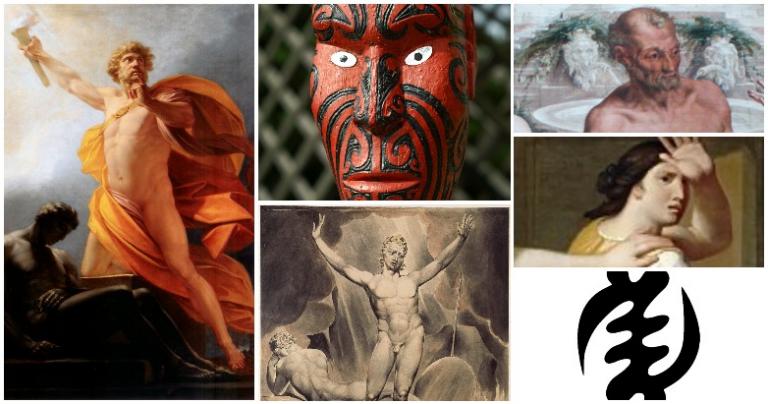

Prometheus: The Titan who defied Zeus to save mankind

Perhaps my favourite rebel deity of all is the Greek titan Prometheus.

I remember reading as a child that it was Prometheus, not Zeus, who created mankind out of clay; Zeus merely breathed life into them. Being mischievous and unafraid of making a mockery of the Olympians, Prometheus tricked Zeus by using his own greed against him. He offered Zeus two sacks – one topped with meat but filled with bones, and one topped with bones but full of meat. Zeus of course accepted the sack with the meat on the top, but when he discovered the deception, he took his rage out on Prometheus’ creation by stealing light and warmth from mankind.

But Prometheus wouldn’t let his beloved mankind suffer. He took fire from the Sun itself to bring back light and warmth to the people.

This sent Zeus into an even greater rage. He punished Prometheus by chaining him to a rock, whereupon an eagle would tear his liver out daily for eternity. And he also inflicted his wrath upon mankind by releasing pain, suffering, disease and evil on to the world.

These myths reveal Prometheus to be the true father of mankind, sacrificing himself in order to bring them the fire they need for life and civilisation. Zeus, on the other hand, is portrayed as a cruel tyrant who torments mankind by depriving them of the necessities for living and progress as well as cursing them with suffering.

As with all myths, symbolism is at work here. Prometheus, whose name means “forethought” and reflects his intelligence, represents man’s intellect and potential. Zeus, on the other hand, is the personification of thunder – the merciless, destructive force of nature. Zeus triumphing over Prometheus could symbolise man’s inability to control nature, and the folly of failing to give nature the proper respect.

I also like to to see some modern symbolism here. In these myths I see Prometheus as the personification of free-thinking, and Zeus as representing the tyranny of enforced religion. Despite Prometheus being the true champion of mankind, he is crushed by the awesome power of the state. And it is Zeus, not Prometheus, who became the ruler of the Olympic gods and the chief of the Greek pantheon.

But there’s a message of hope here. Zeus does not kill Prometheus – indeed, perhaps he cannot. Prometheus may be oppressed and tortured, but he is not eradicated completely, and has the potential to break free. In some stories, Prometheus is liberated by Heracles – the son of Zeus himself. I think this is vital message for freethinkers, secularists, atheists and all others who suffer under the oppression of organised religion; that ideas of liberty and justice cannot die.

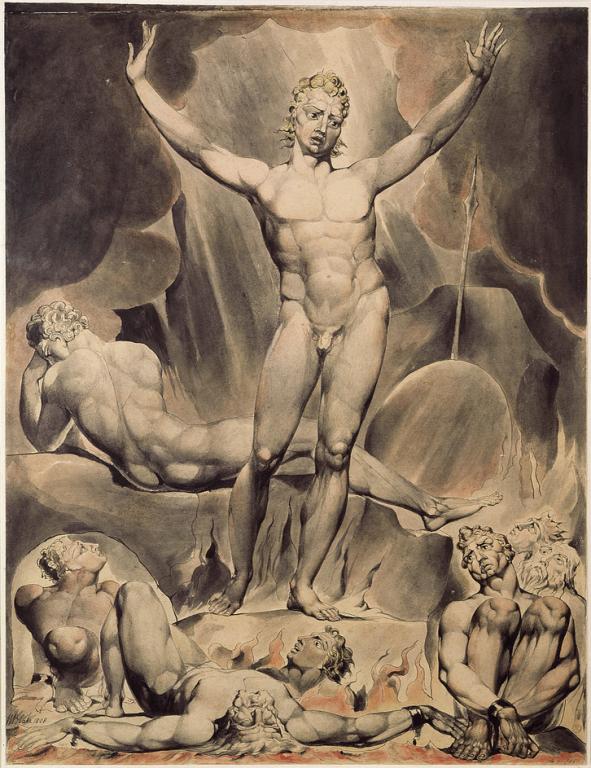

Satan: The bringer of the light of knowledge

One cannot talk about mythological rebels without talking about the ultimate Abrahamic antagonist: the Devil, Satan, Shaitan, Iblis, Lucifer.

The Devil is the great opponent of God, who is attributed with causing worldly sufferings and tempts mankind into going against God’s will. Perhaps his most significant act is his temptation of Eve. While in the Garden of Eden, God instructs Adam and Eve not to eat the fruit of the tree of knowledge. But a snake persuades Eve to take the fruit and eat with Adam. As a result, Adam and Eve gain forbidden knowledge, and are expelled from the Garden. The snake is usually identified as Satan.

Satan is commonly regarded as a fallen angel who disobeyed God and was expelled from Heaven to Hell, where he is both tortured and torturer of the souls of sinners.

We have primarily John Milton to thank for the enduring depiction of Satan as a rebel, as characterised in Milton’s Paradise Lost. Milton depicted Satan as a complex, audacious character who is a skilled general, a brilliant orator and a master schemer. Satan persuades other angels into waging war against a God who he portrays as tyrannical and hypocritical. It’s easy to find sympathy with such a character. And in fact, Milton was almost certainly inspired by the myths of Prometheus in his characterisation of Satan.

In modern times, the name Satan is synonymous with Lucifer, meaning “light bearer.” Originally a reference to the “morning star” (i.e. Venus) or to the Moon, the various characters referred to as Lucifer have in time become entangled with Satan. But the name serves to reinforce the idea of Satan as a Prometheus-like character who brings light to the people – in this case, the light of knowledge forbidden in the Garden of Eden but released through the actions of the serpent. Like Prometheus, Lucifer serves as a metaphor of the battle of human intellect, knowledge and freethought against tyrannical religious authoritarianism.

Throughout history, Abrahamic religions have connected Satan to other religions that threaten their supremacy. Traditional iconography of Satan, in which he is depicted a horned, bearded man with the legs and tail of a goat, are almost certainly based on the Greek god of the wilds, Pan. Associations of the Devil with snakes and dragons may be an attempt to demonise earlier religions involving snake-worship.

Even today, we see religions being accused as blasphemic forms of devil-worship in order to victimise their followers. Pagans know full well that fundamentalist Christians consider them to be devil-worshippers and they occasionally suffer harassment as a result. Despite usually being Catholic, followers of the growing cult of Santa Muerte are accused of devil-worship by the Catholic Church. Perhaps the biggest victims are currently the Kurdish Yazidis, who are called devil-worshippers by Islamic fundamentalists and are suffering a campaign of persecution and genocide.

Actual religions based on the biblical Satan do exist, but very rarely in forms characterised by illegal acts or acts considered “evil” in the usual sense. The most successful Satanic movements share the idea of Satan as a symbol of freedom, rebellion and justice for the individual against religious control or persecution. It’s no coincidence that one of the most prominent Satanic movements of today, the Satanic Temple, is a secularist movement that campaigns for human rights over religious privilege. Take a look at their mission statement:

The mission of The Satanic Temple is to encourage benevolence and empathy among all people, reject tyrannical authority, advocate practical common sense and justice, and be directed by the human conscience to undertake noble pursuits guided by the individual will. Politically aware, Civic-minded Satanists and allies in The Satanic Temple have publicly opposed The Westboro Baptist Church, advocated on behalf of children in public school to abolish corporal punishment, applied for equal representation where religious monuments are placed on public property, provided religious exemption and legal protection against laws that unscientifically restrict women’s reproductive autonomy, exposed fraudulent harmful pseudo-scientific practitioners and claims in mental health care, and applied to hold clubs along side other religious after school clubs in schools besieged by proselytizing organizations.

Momus: The gods’ critic

The son of Nyx (night), Momus is the personification of satire and mockery in the Greek tradition. Whatever the gods of Olympus achieved, Momus would point out the flaws.

One Aesop’s fable has Momus judging three of the gods’ creations: a man, a house and a bull. Momus finds fault with all three – he says that the man’s heart should be on display to show his true feelings, the house should have wheels to avoid troublesome neighbours, and the bull should have eyes in its horns to guide it when charging. As a result of his constant criticism, Momus was eventually cast down from Mount Olympus.

In the 16th century, the Dutch humanist Erasmus presented Momus as a champion of criticising authority. He wrote that Momus was “not quite as popular as others, because few people freely admit criticism, yet I dare say of the whole crowd of gods celebrated by the poets, none was more useful.” Later in the 17th century, Momus became a figure of fun and satire as an archetypal Fool.

Momus is a reminder that no person, and no idea, is above criticism – a vital aspect of secularism, free speech and the fight against religious oppression.

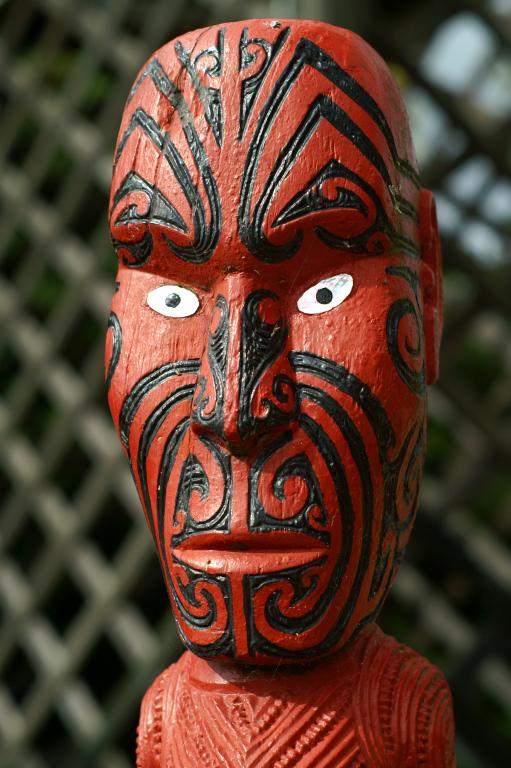

Māui: The Trickster Champion Of Mankind

Māui uses his skills to restrain the Sun and force it to travel more slowly in the sky so that the people can enjoy longer daylight hours. He uses is own blood to bait huge fish to the surface, creating islands for people to live on. He goes to the Fire-Goddess Mahuika in order to trick her into teaching him the secrets of fire for his people, and in doing so is nearly killed by the wrathful goddess.

In the end, he tries to seek immortality for humanity by entering the body of Hine-nui-te-pō,, Goddess of the Night. Unfortunately, he is crushed to death on his escape. He is yet another deity who sacrifices himself in an act of rebellion and the quest for knowledge and progress.

Anansi: The Cunning Trickster

Anansi’s a tricky character to place, and not merely because he’s a trickster. He’s more of a folk hero than a god, but his significance in West African and Caribbean folklore, coupled with his possible links to the creator god Nyame of the Akan religion, means that I didn’t want to leave him out.

The inspiration behind the “Brer Rabbit” stories you may have heard as a child, Anansi the spider-man’s tales of cunning often contain a moral message. The most well-known Anansi story in the west is probably the tale of how Anansi obtained all the world’s stories from the powerful Sky-God Nyame.

Nyame set Anansi the task of capturing some of the most feared creatures in the jungle, but using his cleverness (together with help from his wife Aso), Anansi succeeded in bringing Nyame all the requested creatures. Nyame had no choice but to give Anansi his stories. Again, another story of a trickster liberating hidden knowledge from a powerful deity – but in this rare case, Anansi actually survives unscathed and unpunished.

Anansi is also significant because he became a symbol of slave resistance and survival. As Wikipedia puts it:

Anansi is able to turn the table on his powerful oppressors by using his cunning and trickery, a model of behaviour utilised by slaves to gain the upper-hand within the confines of the plantation power structure. Anansi is also believed to have played a multi-functional role in the slaves’ lives; as well as inspiring strategies of resistance, the tales enabled enslaved Africans to establish a sense of continuity with their African past and offered them the means to transform and assert their identity within the boundaries of captivity.

Anansi is therefore a very real source of inspiration for those fighting oppression.

Arachne: The brave blasphemer

Arachne has never been regarded as a deity, but I believe her story is so important that I wanted to include her too, especially because, like Anansi, she is connected to spiders.

In Greek mythology, Arachne was a talented mortal weaver. So talented in fact that her skill was comparable to that of Athena, the goddess of wisdom and craft. And Arachne knew it, and was not afraid to point this out.

One day, an old woman came to Arachne, telling her to stop comparing herself to the gods and that she would be forgiven if she ceased. But Arachne remained defiant, claiming that she spoke only the truth and that Athena should come and challenge her herself if she thought otherwise. At once, the old woman threw off her disguise to reveal herself as none other than the goddess Athena. However, Arachne stood her ground and, true to her word, challenged Athena to a weaving contest.

Arachne’s contest proved to be her bravest act of blasphemy. For not only did she produce a piece of weaving that was, in fact, better than Athena’s, but she also used her skills to depict the gods as she truly saw them. While Athena’s piece portrayed the gods as noble and proud rulers of Olympus, Arachne depicted them as drunken fools abusing mortals, including Zeus’ hideous treatment of women. In a rage of jealousy and humiliation, Athena tore up Arachne’s work, beat Arachne with her weaving shuttle, and turned her into a spider.

I see Arachne as the heroine of this story. No matter how much Athena tried to intimidate her, she refused to hide her extraordinary talents and furthermore, used those talents to tell the gods some painful truths. Although she was punished for her actions, one cannot help but feel that perhaps Arachne won out in the end. Spiders are indeed perhaps nature’s greatest weavers, and their ability to build such strong webs are still something of a mystery to humans. Arachne perhaps achieved immortality in a way that Athena could only dream of.