In my last post, I argued that Humanists who believe environmentalism is anti-Humanists are incorrect, in that environmentalism seeks to protect the interests mankind. Now let’s look from the reverse perspective – at how some environmentalists perhaps need to adopt a more Humanist perspective, and always factor in human rights as a basic component of conservation.

What prompted me to think about this was watching BBC’s The Hunt last year, a David Attenborough documentary about nature’s predators and how they live. While for the most part it’s an excellent series, I found the final episode a little disturbing. It was about the very real need for conservation of top predators, but some of the methods highlighted made me uncomfortable.

In once instance, they showed how a small, not especially wealthy community in India was incentivised to move from their isolated forest-based village to a more urban area in order to make more room for tigers. Although the villagers were given compensation to move, my impression was that little else was done to ensure they could continue to make a living, and many villagers seemed unhappy with this relocation – understandably so. What’s more, the tiger specialist in charge of the project argued that these villagers would be better off in the urban area, where he said there would be better access to education and so forth, than in their original forest home. I’ve heard propaganda like this used many times to justify the forced relocation of tribal peoples and others who choose to live in isolated areas away from large settlements, and it was frightening to hear such ideas here. One wonders how much say the villagers had in this re-location and whether it was genuinely done for the sake of conservation, or had a more political end in mind.

In another scene, we saw two white conservationists travelling to East Africa to confront the Maasai people over their killing of lions. Since they depend entirely on cattle for their diet, defending herds from lions is simply a part of life for the Maasai; the documentary noted that the Maasai have lived alongside lions for “thousands of years.” Lions are also be hunted for ritual purposes by the Maasai, particularly as a rite of passage. But these white conservationists took it upon themselves to tell the Maasai that this ancient way of life is wrong, and that they shouldn’t kill lions.

This smacked so much of a particularly old-fashioned brand of cultural imperialism that it was difficult to watch. True, lions are classified as “vulnerable” (but not “endangered”) by IUCN and their numbers are declining, but picking on a group of indigenous tribesmen who take a few lions every year in order to defend their cattle is not going to solve the problem. All it does is give the governments of Kenya and Tanzania more incentive to put pressure on the Maasai people to abandon their traditional way of life – a way of life that the Maasai would very much like to retain. This form of environmentalism in fact drives a wedge between nature and the people who live within it. The Maasai understand more than anyone that if they want to continue their way of life, which includes the ritual hunting of lions, they need to hunt them responsibly to make sure they do not wipe them all out (hence the hunting in such small numbers). They don’t need outsiders who have never experienced Maasai life wagging their fingers and giving them a ticking off for killing lions. Meanwhile, lion numbers continue to plummet due to issues that have nothing to do with the Maasai, including destruction of their habitat and trophy hunting by rich tourists. If we want to help lions, these are the issues that we need to be tackling, not picking on tribal people. I certainly did not miss the irony that The Hunt, which celebrates the incredible abilities of nature’s most awesome predators, seemed to condemn the actions of the Maasai – the most inventive, brilliant and successful hunters of all on the East African plains.

Conservation is hard, and finding solutions that satisfy the needs of people and the rest of the environment can be a minefield. But we must not be tempted by the “easy option” of victimising the most vulnerable targets – be they ordinary villagers in India or Maasai tribes in Africa – to try and solve these problems.

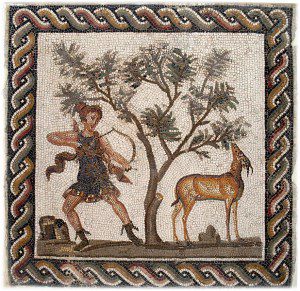

As Pagans, we are aware that human beings are just as part of nature as any other animal in the ecosystem. That is why I believe, as a Pagan and as a Humanist, actions carried out in the name of environmentalism and conservation must be conducted in a way that ensures human rights are not violated in the process. Pagan Gods and Goddesses of hunting were often the same Gods and Goddesses who protected nature too. The message theses deities taught was that using the natural resources around you to live is a good thing, as long as it is done properly and with respect. Those who cause upheaval in the lives of ordinary people in the name of environmentalism seem to have forgotten this message.

Fortunately, there are environmentalists who realise that conservation that includes humans as part of the ecosystem to preserve and treasure is a better way to go. I strongly recommend watching BBC’s Human Planet, the best documentary series ever made in my opinion, which explores the many ingenious ways humans around the world live sustainably side-by-side with nature.

If you are interested in finding out more about the conflicts that arise between environmentalism and the human rights of tribal peoples, and want to help support those who choose to live in tribal communities, please do check out the charity Survival International.